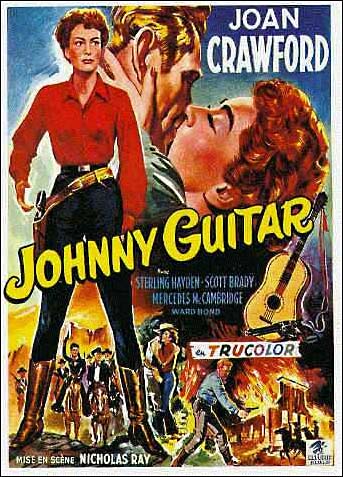

Is there any way to announce a consideration of Johnny Guitar other than the now famous Jean-Luc Godard quote about Nicholas Ray being “cinema”? Famously, the director expressed that Ray was among the first, if not the first, American auteurs to do with cinema as only cinema could, taking up the poetry of dialogue and the untarnished, painterly quality of art and the distant timelessness of theater and encircling them with the vulture of film, engorging itself on the carcasses of other mediums and ensuring they lived on, in altered, transmuted form, inside cinema.

Is there any way to announce a consideration of Johnny Guitar other than the now famous Jean-Luc Godard quote about Nicholas Ray being “cinema”? Famously, the director expressed that Ray was among the first, if not the first, American auteurs to do with cinema as only cinema could, taking up the poetry of dialogue and the untarnished, painterly quality of art and the distant timelessness of theater and encircling them with the vulture of film, engorging itself on the carcasses of other mediums and ensuring they lived on, in altered, transmuted form, inside cinema.

Godard’s quote is a touch too heated (I’ll take to my grave the thought that Nicholas Ray is among the most underrated auteurs Hollywood ever produced, but that he was the first true advocate of “cinema” is a much more difficult proposition). Certainly, however, Ray’s films always felt more alive with pulsation, even in their embalmed detachment, than those of many other auteurs. And Godard naturally felt the love due to Ray’s unparalleled work in genre as a means of classifying social incoherence and expressing differing views of humanity’s own artifice. If he wasn’t the first true cinematic visionary, he was up there with the greats of his or any other time. Continue reading

Update upon another viewing in 2017:

Update upon another viewing in 2017: A Serious Man

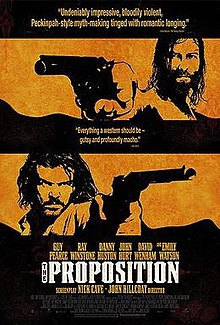

A Serious Man The significant resurgence of the Western genre since about 2005 (for reasons I’m not entirely sure of) is one of the few truly surprisingly revelations from the cinematic world to be found this past decade. It’s all the more notable particularly because the Westerns themselves have taken so many different forms, from pure, effervescent myth-making, to black-hearted heaving gasps of grimy moral decay, to slowly gliding, almost Impressionist location tapestries where characters serve merely as extensions of the environment, to plain ol’ rootin-tootin shoot em’ up character studies.

The significant resurgence of the Western genre since about 2005 (for reasons I’m not entirely sure of) is one of the few truly surprisingly revelations from the cinematic world to be found this past decade. It’s all the more notable particularly because the Westerns themselves have taken so many different forms, from pure, effervescent myth-making, to black-hearted heaving gasps of grimy moral decay, to slowly gliding, almost Impressionist location tapestries where characters serve merely as extensions of the environment, to plain ol’ rootin-tootin shoot em’ up character studies. Edited and Updated 2016

Edited and Updated 2016 Edited

Edited Unforgiven is about as gutsy and ravaged a film as you’ll find from a mainstream American director, a work which not only deconstructs a genre of film but the filmmaker’s entire career. It’s seeped in merciless violence, but as much a violence which occurred decades before the film begins as any violence which occurs from first reel to denouement. It rolls over the arid hills of the American West, bathed in a dark, ominous red of the blood done in the past but which refuses to be forgotten. With Unforgiven, Eastwood not only tears down the violent core of America’s past, but he has a few choice words for the gaze we place upon violence in modern society. We’re fascinated with it. And Eastwood, a man whose career was built on celluloid violence, knows this well. He runs us through the wringer with quiet, elegiac visual poetry which provides us with a dreamy, mythic Western landscape and that turns out to be a nightmare clinging us to our past. This is cinema of implication, with Eastwood questioning whether we can ever break from the horror-show of the Western genre and underlining his question in blood-red strokes.

Unforgiven is about as gutsy and ravaged a film as you’ll find from a mainstream American director, a work which not only deconstructs a genre of film but the filmmaker’s entire career. It’s seeped in merciless violence, but as much a violence which occurred decades before the film begins as any violence which occurs from first reel to denouement. It rolls over the arid hills of the American West, bathed in a dark, ominous red of the blood done in the past but which refuses to be forgotten. With Unforgiven, Eastwood not only tears down the violent core of America’s past, but he has a few choice words for the gaze we place upon violence in modern society. We’re fascinated with it. And Eastwood, a man whose career was built on celluloid violence, knows this well. He runs us through the wringer with quiet, elegiac visual poetry which provides us with a dreamy, mythic Western landscape and that turns out to be a nightmare clinging us to our past. This is cinema of implication, with Eastwood questioning whether we can ever break from the horror-show of the Western genre and underlining his question in blood-red strokes.

Edited

Edited