I would so deeply have loved to claim that Pitch Perfect 2 takes advantage of its premise with a tidal wave of bubbly, giddy affection and camaraderie that even I, born and bred A Capella enemy, could be swayed by its sheer cataclysmic force and gallant reluctance to submit to the screenwriting essentials of the cinematic world. By all accounts, the original Pitch Perfect (unseen by me) was an achievement primarily for its low-key, shaggy-dog bonding and unforced, almost non-narrative chill-out vibe. Ideally, in Pitch Perfect 2, singing scenes would double as bonding sequences for characters, and individual moments of plucky, even spunky, post-narrative fluff doctored up with flashy camera movements and zippy staging and framing would be the order of the day .

I would so deeply have loved to claim that Pitch Perfect 2 takes advantage of its premise with a tidal wave of bubbly, giddy affection and camaraderie that even I, born and bred A Capella enemy, could be swayed by its sheer cataclysmic force and gallant reluctance to submit to the screenwriting essentials of the cinematic world. By all accounts, the original Pitch Perfect (unseen by me) was an achievement primarily for its low-key, shaggy-dog bonding and unforced, almost non-narrative chill-out vibe. Ideally, in Pitch Perfect 2, singing scenes would double as bonding sequences for characters, and individual moments of plucky, even spunky, post-narrative fluff doctored up with flashy camera movements and zippy staging and framing would be the order of the day .

Pitch Perfect 2, unfortunately, makes the mistake of thinking it is a real film with things like a narrative, and it desperately, punishingly wishes that we accept this unearned narrative fixation from the get-go. The premise – the Barden Bellas, an all-female A Capella group, accidentally cause a snafu in front of the First Family of the United States, and the group has to win an international A Capella tournament in order to get their good name back, is functional and fine. But on top of this, the film piles a pair of romances, inter-group friction about the future of the Bellas, and a secret internship for main Bella Beca Mitchell (Anna Kendrick) in her attempt to enter the music recording industry that causes an identity crisis and a handful of solid belly laughs from Keegan-Michael Key. Continue reading

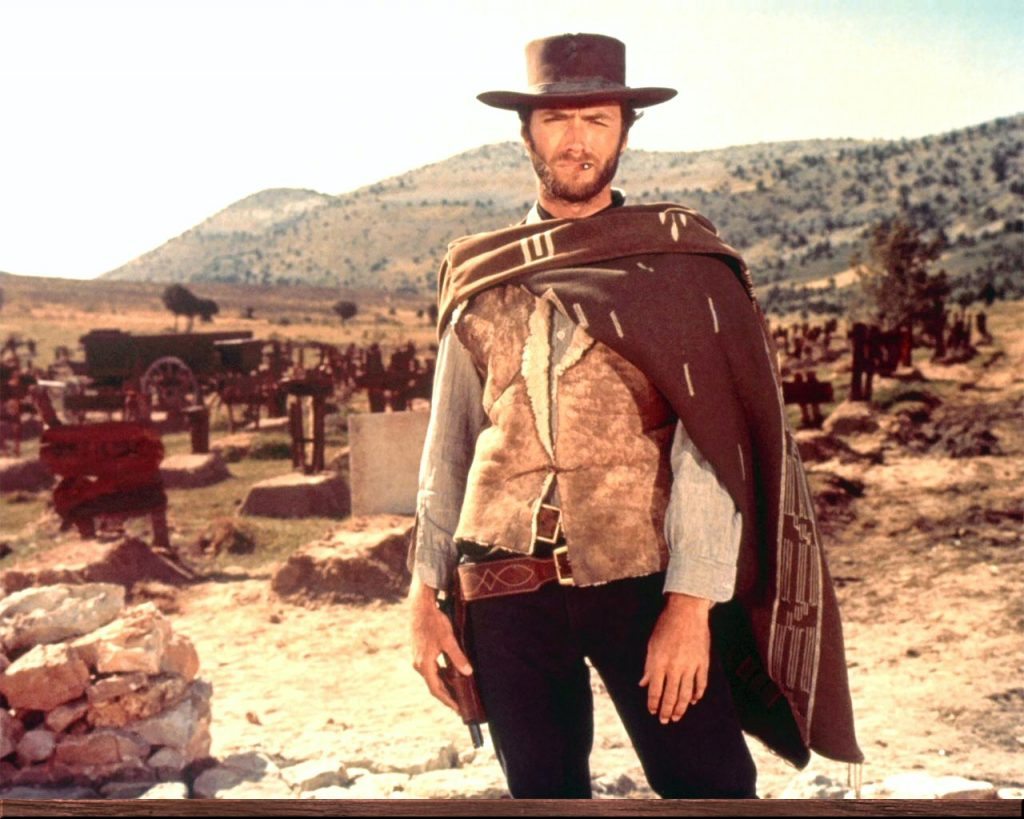

Reviewing the quintessential Euro-cool movie of the 1960s gave me the idea to add on a little bonus review of perhaps the most European of the “cool American” films of the decade, a truly great work of experimental pop from the master of not deciding whether his film would be amazing or awful, John Boorman…

Reviewing the quintessential Euro-cool movie of the 1960s gave me the idea to add on a little bonus review of perhaps the most European of the “cool American” films of the decade, a truly great work of experimental pop from the master of not deciding whether his film would be amazing or awful, John Boorman… Edited

Edited Our Man Flint is not the best film to wield as a cipher for the amorphous concept of “camp”, but it is sufficiently campy to justify bending an analysis in the direction of camp. Arguably, a better film would be the following year’s Batman: The Movie, but although Batman is probably the better film as far as outright absurdism goes, Our Man Flint feels more honestly campy. This may seem patently ridiculous, but a further dissection of what exactly camp is (and exploring pop in the ’60s absolutely insists on a discussion of camp) helps us understand why Flint is a work of camp while Batman moves back and forth between camp and something more openly satiric. The privilege of Batman is the privilege of satire, namely that it has the confidence of its own superiority to the world of the “serious”, and that is not something Our Man Flint even considers.

Our Man Flint is not the best film to wield as a cipher for the amorphous concept of “camp”, but it is sufficiently campy to justify bending an analysis in the direction of camp. Arguably, a better film would be the following year’s Batman: The Movie, but although Batman is probably the better film as far as outright absurdism goes, Our Man Flint feels more honestly campy. This may seem patently ridiculous, but a further dissection of what exactly camp is (and exploring pop in the ’60s absolutely insists on a discussion of camp) helps us understand why Flint is a work of camp while Batman moves back and forth between camp and something more openly satiric. The privilege of Batman is the privilege of satire, namely that it has the confidence of its own superiority to the world of the “serious”, and that is not something Our Man Flint even considers. To truly review a film, you should go in accepting its basic existence. Specifically, you should debate with the concept, make peace with it, and develop your critical faculties to move beyond criticisms of a film’s idea and toward criticism of the execution to fulfill that idea. You should go in accepting everything you could know about the movie simply by seeing the trailer or the poster, or else your criticism should be taken with a most sodium-infused grain of salt.

To truly review a film, you should go in accepting its basic existence. Specifically, you should debate with the concept, make peace with it, and develop your critical faculties to move beyond criticisms of a film’s idea and toward criticism of the execution to fulfill that idea. You should go in accepting everything you could know about the movie simply by seeing the trailer or the poster, or else your criticism should be taken with a most sodium-infused grain of salt. George Miller really wanted Mad Max: Fury Road. The back-story, the thirty year gap between Fury Road and its predecessor Mad Mad: Beyond Thunderdome, and the troubled, stop-start production for Fury Road itself all conspire to tell us this much. The beauty of the resulting film is that this back-story is both instantly extraneous and essential to unlocking its mysteries. All the hurt, all the torment, all the passion to release that which had been denied to Miller; all are instantly identifiable on the screen, but the film speaks for itself. Right before it blows your head off, but that is the Miller way. After releasing two extraordinary vehicles for tactile, sand-encrusted action under the Mad Max name, he went Hollywood and lost his edge with the third feature, the one whose biggest addition was Tina Turner. He spent the ensuing thirty years intermittently pursuing his craft in often stellar family films to recuperate, but his heart was elsewhere.

George Miller really wanted Mad Max: Fury Road. The back-story, the thirty year gap between Fury Road and its predecessor Mad Mad: Beyond Thunderdome, and the troubled, stop-start production for Fury Road itself all conspire to tell us this much. The beauty of the resulting film is that this back-story is both instantly extraneous and essential to unlocking its mysteries. All the hurt, all the torment, all the passion to release that which had been denied to Miller; all are instantly identifiable on the screen, but the film speaks for itself. Right before it blows your head off, but that is the Miller way. After releasing two extraordinary vehicles for tactile, sand-encrusted action under the Mad Max name, he went Hollywood and lost his edge with the third feature, the one whose biggest addition was Tina Turner. He spent the ensuing thirty years intermittently pursuing his craft in often stellar family films to recuperate, but his heart was elsewhere.  What a strange, messy phenomenon the Pink Panther franchise is. When it began in 1963 as a slight, indifferently pleasant movie about a jewel thief (played by the ever-smarmy David Niven, who was given the lion’s share of the run-time) and an inept side-character vaguely pretending to hunt him down , expectations for a sequel, let alone a cottage pop culture phenomenon, were little. Now, the first film, The Pink Panther, did not exactly set the world on fire, nor does it truly qualify as a phenomenon. But relative to what it might have been – a throwaway ’60s fluffy star piece with some entirely game actors in the distinctly ’60s laconic-swinging mode so ubiquitous in 1963 – something caught fire.

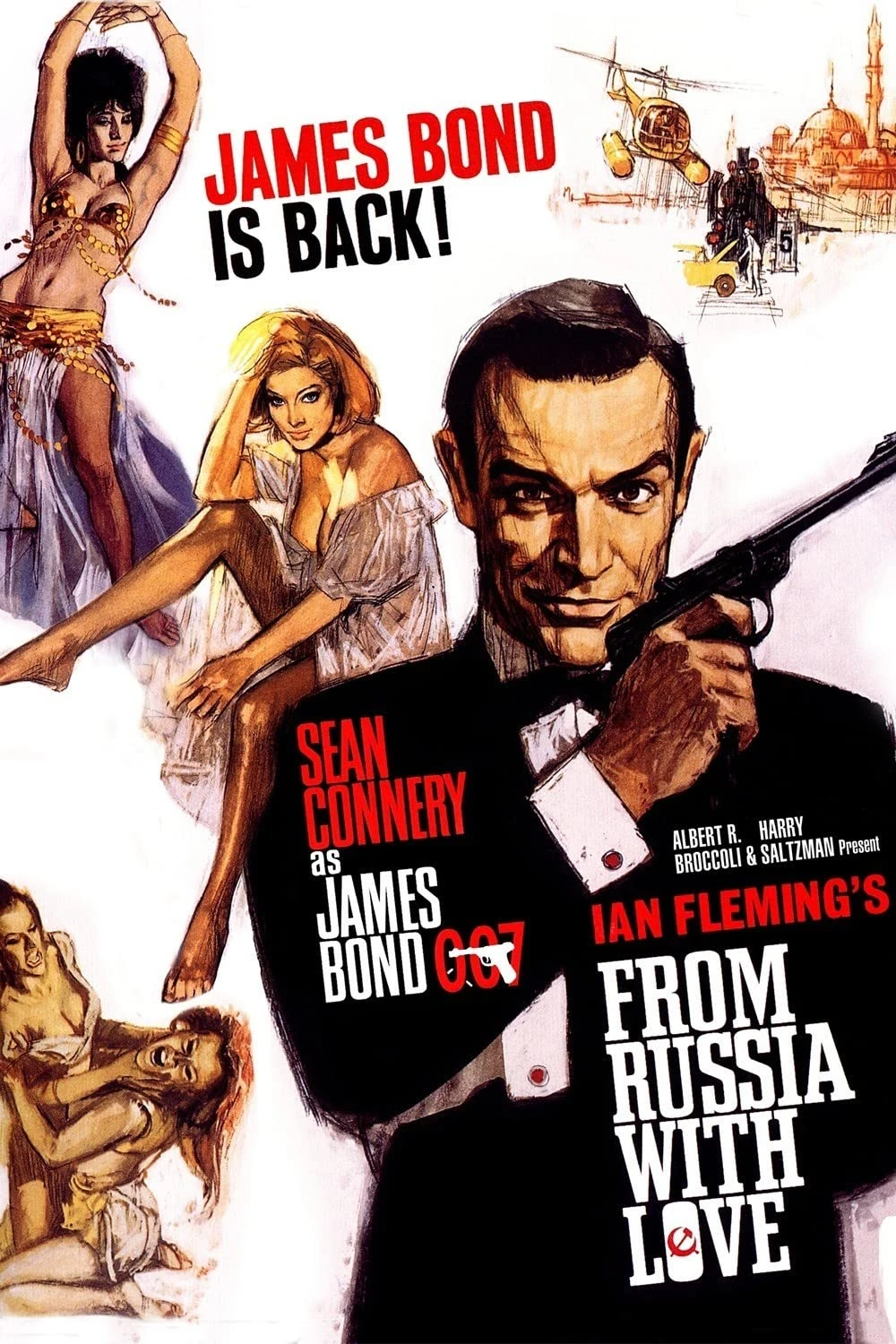

What a strange, messy phenomenon the Pink Panther franchise is. When it began in 1963 as a slight, indifferently pleasant movie about a jewel thief (played by the ever-smarmy David Niven, who was given the lion’s share of the run-time) and an inept side-character vaguely pretending to hunt him down , expectations for a sequel, let alone a cottage pop culture phenomenon, were little. Now, the first film, The Pink Panther, did not exactly set the world on fire, nor does it truly qualify as a phenomenon. But relative to what it might have been – a throwaway ’60s fluffy star piece with some entirely game actors in the distinctly ’60s laconic-swinging mode so ubiquitous in 1963 – something caught fire. From Russia with Love is a curious beast. It does not “work” according to the distinct rhymes and reasons of what would become the “Bond film” archetype. It does not establish its own vision of what cinema ought to be, as so many other Bond films went on to do, starting with the very next film in the series, Goldfinger. It lacks the pop art, it lacks the pizzaz, it lacks the chutzpah of those other glammy, punchy Bond films that established a certain modern cool-chic lifestyle porn take on watching movies simply because they could give you visions of things that life in its mundane reality never could. On most of the basic “rules” by which Bond films are generally judged, it doesn’t even attempt to pass muster. In fact, it is, excepting its predecessor Dr. No, a work that could charitably be described as “mundane”.

From Russia with Love is a curious beast. It does not “work” according to the distinct rhymes and reasons of what would become the “Bond film” archetype. It does not establish its own vision of what cinema ought to be, as so many other Bond films went on to do, starting with the very next film in the series, Goldfinger. It lacks the pop art, it lacks the pizzaz, it lacks the chutzpah of those other glammy, punchy Bond films that established a certain modern cool-chic lifestyle porn take on watching movies simply because they could give you visions of things that life in its mundane reality never could. On most of the basic “rules” by which Bond films are generally judged, it doesn’t even attempt to pass muster. In fact, it is, excepting its predecessor Dr. No, a work that could charitably be described as “mundane”. America did pop proud in the 1960s, but pop didn’t always imply a bulging budget or grandiose popular success. The lingering vestiges of that most ’50s of all genres, the atomic underground horror, still clung to the beginning of the decade like a wandering specter. Admittedly, the low-brow, even-lower-budget works suffered a little about how to re-invent themselves; Hammer Horror in the UK certainly hit a few home runs, but flooding the markets ran them red with bloody boredom sooner than not. In the US, where “underground fare” similarly served as a safe, parental euphemism for horror, things were likewise stuck in a liminal space between the pre-Bay of Pigs interest in fooling around with atomic supermen and nuclear fall-out monsters, and the genuine “exploitation” of exploitation cinema came to fruition in the very late 1960s. In between, in the early 1960s, what was underground horror to do?

America did pop proud in the 1960s, but pop didn’t always imply a bulging budget or grandiose popular success. The lingering vestiges of that most ’50s of all genres, the atomic underground horror, still clung to the beginning of the decade like a wandering specter. Admittedly, the low-brow, even-lower-budget works suffered a little about how to re-invent themselves; Hammer Horror in the UK certainly hit a few home runs, but flooding the markets ran them red with bloody boredom sooner than not. In the US, where “underground fare” similarly served as a safe, parental euphemism for horror, things were likewise stuck in a liminal space between the pre-Bay of Pigs interest in fooling around with atomic supermen and nuclear fall-out monsters, and the genuine “exploitation” of exploitation cinema came to fruition in the very late 1960s. In between, in the early 1960s, what was underground horror to do?