A tempest of Murnau, Borzage, and Griffith with its own achingly sensual, mist-shrouded, potently translucent vision of city life and the mystique of human desire, Josef von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York is one of the pinnacles of American silent drama in the year of its acme. Which was, coincidentally, the year of its sputtering death throes, almost as if the pre-sound era was firing on all cylinders to stave off the phantom of sound, to preserve the crystalline purity of the visual medium and acclimatize viewers to the potency of the screen itself, and, above all, to throw itself the most divine combination going-away party and sarcophagus it could muster from its own hands. If so, Victor Sjöström’s The Wind might be the mortal specter of tenuous life, the skeleton in the casket, and Murnau’s Sunrise could be the grand, angelic denouement, the swooping saving grace to send the silents off to Asgard or some other heavenly resting place after being tempted by fate. I think it fitting that The Docks of New York would only ever take pride of place at silent cinema’s funeral as the drunken after-party, with the blissful ignorance of acceptance slurring around a fear of the future that is still waiting in the wings. Continue reading

A tempest of Murnau, Borzage, and Griffith with its own achingly sensual, mist-shrouded, potently translucent vision of city life and the mystique of human desire, Josef von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York is one of the pinnacles of American silent drama in the year of its acme. Which was, coincidentally, the year of its sputtering death throes, almost as if the pre-sound era was firing on all cylinders to stave off the phantom of sound, to preserve the crystalline purity of the visual medium and acclimatize viewers to the potency of the screen itself, and, above all, to throw itself the most divine combination going-away party and sarcophagus it could muster from its own hands. If so, Victor Sjöström’s The Wind might be the mortal specter of tenuous life, the skeleton in the casket, and Murnau’s Sunrise could be the grand, angelic denouement, the swooping saving grace to send the silents off to Asgard or some other heavenly resting place after being tempted by fate. I think it fitting that The Docks of New York would only ever take pride of place at silent cinema’s funeral as the drunken after-party, with the blissful ignorance of acceptance slurring around a fear of the future that is still waiting in the wings. Continue reading

Golden Age Oldies: Pandora’s Box

Temptation begs to flatten G.W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box by giving it a moralizing voice or treating it as a statute on character worth, in doing so succumbing to the bourgeois decree to dress up the film in airs that Pabst, and certainly main character Lulu, have no earthly use for. Played by Louise Brooks in a phenomenal tantrum of a performance at the heart of what is inherently a melodramatic sideshow of a film, Lulu is a man-killer and an earthquake but also an embodiment of the implacable drive to not only persist but discover oneself at the heart of the human condition. In a world that is a playground and a hot-house of self-discovery and self-preservation, our earthen notions of morality don’t really apply. Continue reading

Temptation begs to flatten G.W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box by giving it a moralizing voice or treating it as a statute on character worth, in doing so succumbing to the bourgeois decree to dress up the film in airs that Pabst, and certainly main character Lulu, have no earthly use for. Played by Louise Brooks in a phenomenal tantrum of a performance at the heart of what is inherently a melodramatic sideshow of a film, Lulu is a man-killer and an earthquake but also an embodiment of the implacable drive to not only persist but discover oneself at the heart of the human condition. In a world that is a playground and a hot-house of self-discovery and self-preservation, our earthen notions of morality don’t really apply. Continue reading

Golden Age Oldies: Applause

p Slinky and unruly by the standards of its time, Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause – a stepping stone onto a proficiently very good if seldom great path as a cross-pollinating genre director – opens with its camera not only on the move but on the war path to prove the director’s ambition. Even the intro’s deceptively near-silent implementation of sound in the far off distance intimates that this is not a complacent motion picture by 1929’s standards. The roving camera more or less an ingrained tool by 1929, it was nonetheless not yet a known quantity, and sound was never as vigorously applied before as it would be in this feature. This knowledge in tow, Applause is a film that obviously shows Mamoulian, in his debut feature, was ready to go to bat with the future of film in his hands. Continue reading

Slinky and unruly by the standards of its time, Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause – a stepping stone onto a proficiently very good if seldom great path as a cross-pollinating genre director – opens with its camera not only on the move but on the war path to prove the director’s ambition. Even the intro’s deceptively near-silent implementation of sound in the far off distance intimates that this is not a complacent motion picture by 1929’s standards. The roving camera more or less an ingrained tool by 1929, it was nonetheless not yet a known quantity, and sound was never as vigorously applied before as it would be in this feature. This knowledge in tow, Applause is a film that obviously shows Mamoulian, in his debut feature, was ready to go to bat with the future of film in his hands. Continue reading

Golden Age Oldies: L’Age d’Or

Legend has it that Luis Buñuel chased partner in crime Salvador Dali off set once the painter – on sabbatical to help discover the possibility of the relatively new medium of film – had done his dirty work helping the madman director renegade against The Powers That Be with the screenplay for L’Age d’Or. Verification of the tall tale or not, the exuberance of the overstatement is appreciated in a film with a ramshackle, manic, antic enough demeanor and a will to treat subtlety as a devout enemy at the gates of its own hyperbolic, spasmodic mind. The story may be a fabrication, but the spirit of it rings true in the gloriously impulsive film the two men produced, a work that files a restraining order against the idea of restraint itself. Continue reading

Legend has it that Luis Buñuel chased partner in crime Salvador Dali off set once the painter – on sabbatical to help discover the possibility of the relatively new medium of film – had done his dirty work helping the madman director renegade against The Powers That Be with the screenplay for L’Age d’Or. Verification of the tall tale or not, the exuberance of the overstatement is appreciated in a film with a ramshackle, manic, antic enough demeanor and a will to treat subtlety as a devout enemy at the gates of its own hyperbolic, spasmodic mind. The story may be a fabrication, but the spirit of it rings true in the gloriously impulsive film the two men produced, a work that files a restraining order against the idea of restraint itself. Continue reading

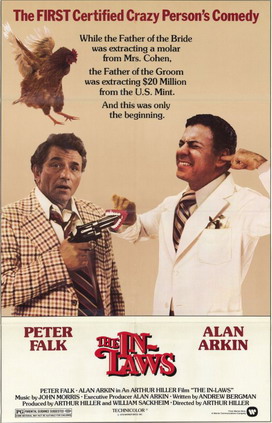

Progenitors: The In-Laws

Central Intelligence is, I am told, a movie about two buddies, one domesticated and the other an epidemic, where one is just maybe an insane rogue agent. Let us look at a much better such film that is mostly forgotten today (and, I must admit, one that is cartoonishly better at evoking the off-kilter is-he-or-isn’t-he-crazy tension that the 2016 half-heartedly, impersonally wishes to suggest).

Central Intelligence is, I am told, a movie about two buddies, one domesticated and the other an epidemic, where one is just maybe an insane rogue agent. Let us look at a much better such film that is mostly forgotten today (and, I must admit, one that is cartoonishly better at evoking the off-kilter is-he-or-isn’t-he-crazy tension that the 2016 half-heartedly, impersonally wishes to suggest).

Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, Martin and Lewis, even Lemmon and whatever straight-man dared tempt Lemmon’s immortal hurricane of manic charisma, all are enshrined in the pantheon of the comic pas de deux. Watching Arthur Hiller’s The In-Laws, Falk and Arkin temporarily feel like the greatest missed opportunity in the two-fisted lexicon of angel-and-devil comedy. They were a one-and-done deal in an over-and-out film that doesn’t so much recapture as reorient classic screwball efforts with a more unhinged ’70s Manhattan edge. Which is, in essence, another match made in heaven: the loose, free-wheeling inertia of the New Hollywood and the dexterity of the Old Hollywood, punching into each other with a recklessness that is becoming of both. Continue reading

Review: The Producers

Mel Brooks turned a gloriously-still-kicking 90 years old this week, and as a happy birthday I’m sure he’ll never read, a review of his debut feature length film.

Mel Brooks turned a gloriously-still-kicking 90 years old this week, and as a happy birthday I’m sure he’ll never read, a review of his debut feature length film.

With Mel Brooks’ directorial debut The Producers (naturally, the writer-by-day writes as well), his most hostile, and therefore best, gesture is to perforate and embrace the Borscht Belt fascination with the essential and unerring failure of life itself. Its mantra being the incompatibility of the self with any semblance of success, the film’s bent is that even in attempting to fail, the only possible outcome for the universe to right itself is for you to inadvertently succeed. And, naturally, fail at your goal of failing. It’s high-concept-y, but more or less to The Producers’ benefit, Brooks plays it all low-brow, helping the film’s philosophical scripture feel more carnal and low-to-the-ground than presumptuous and high-minded. Continue reading

Progenitors: Casino Royale

House cleaning with a review from many months ago I never got around to publishing. It’s the films ten-year anniversary as the best blockbuster from 2006, and what with the blockbusters this year falling down left and right with no idea what on earth they’re doing, the time seems right.

House cleaning with a review from many months ago I never got around to publishing. It’s the films ten-year anniversary as the best blockbuster from 2006, and what with the blockbusters this year falling down left and right with no idea what on earth they’re doing, the time seems right.

2015’s Spectre introduced its reptilian British assassin with that film’s best scene, Bond slithering through the streets of Mexico City in death’s garb like the brutal, unerring slasher he truly is. The decade prior reenvision of the character, Casino Royale, essentially charts the trajectory of the human parts that were refigured into that primeval, thuggish bloodhound ready for the kill. In Royale’s final image, the man accepts the destruction of his humanity and embraces his icon status by restating his franchise-player name, his signature phrase, as he had for decades. Only this time, he does it with a cold-blooded emptiness broken only by the light of a devilish smirk, the fallout of which is essentially the audience’s awareness that his fractured psyche has reduced him to a mercenary whose only joy in life could be to mercilessly raise hell and find some iota of purpose in it. Casino Royale’s climax, its very final image, is less heartbreaking than a question mark about whether there was ever a heart to break, a state of the union address for action cinema that lays bare the terrifying reality that the world, the audience, and the franchise, would rather just have Bond on a leash to do its bidding than be a human. Continue reading

Midnight Screenings: Southern Comfort and Manhunter

Southern Comfort

Southern Comfort

Betwixt his only-now-a-classic neo-pulp comic book New York odyssey, The Warriors, and the even-then-classic trip out West to bad-tempered San Francisco with the anarchic buddy cop picture 48 Hrs., director Walter Hill’s bracing modernist thriller filmmaking took an intentional excursion down South into the fetid swamps of Louisiana. The resulting film, the mostly unknown Southern Comfort, lets itself be engulfed by the jaundiced spirit of the malarial bayou, resulting in a protoplasmic blast of downtuned terror in which awareness of one’s own impotency in a foreign land clings to you like molasses.

Released in 1981, only the most unawares viewer could possibly miss the Vietnam parable at heart in Comfort, an inverse of The Warriors, Hill’s masterpiece and a film more-or-less about the tentative, tenuous connections within groups just waiting for a chance to dissolve into entropy. In The Warriors, death isn’t catalyzed by some inadvertent journey to hostile, unknown territory but from thrashing about in lands one mistakenly assumed to be one’s own. In Comfort, in contrast, it is pitilessly apparent that America’s mental safeguard isn’t the assumption that America is always at home, but that America is innately better than the outside world. Continue reading

Midnight Screenings: Bug and The Hunted

Two modern William Friedkin films (the man responsible for the de facto midnight classic The Exorcist) from his generally underappreciated 21st century career.

Bug

Bug

Borrowing the narrative efficiency of director William Friedkin’s previous film The Hunted but inverting the no-emotion-allowed melancholy and frightening objectivity, Bug is an affectively charged full-on assault of sticky predator-prey dynamics and visually and aurally hissing subjectivity. By some definition a head-scratcher, Friedkin’s adaptation of Tracey Letts’ esteemed play (here scripted by Letts as well) gallantly avoids the nullifying narrative histrionics of most ‘00s “screw with the audience” cinema. Rather than throttling us with narrative momentum and thereby affording his film no breathing room, Friedkin visualizes the subjective mental combat of the material by ricocheting us around a stylistic, mentally expressive pinball machine. Continue reading

Film Favorites: Ivan’s Childhood

Visually garrulous and verbally unobtrusive, Ivan’s Childhood is perhaps the platonic ideal of the director-is-born image, a fully-formed debut for the ages. A film riddled with the ideas that would eventually molt into Tarkovsky’s future six feature films, a diminutive career (seven including this film) by any standards, Ivan’s Childhood lays the groundwork for Tarkovsky’s unmooring of the cinematic consciousness into realms both indescribably beautiful and thoughtfully revelatory. Then again, “eventually” doesn’t do justice to Ivan’s impossible grandeur and fractured intimacy; on its own terms, had the greatest director of the last fifty years not pursued a career in film at all and absconded from sight leaving only this singular mark of his trespass on our earthly realm, he would still be one of the definitive directors of the second half of the twentieth century. Continue reading

Visually garrulous and verbally unobtrusive, Ivan’s Childhood is perhaps the platonic ideal of the director-is-born image, a fully-formed debut for the ages. A film riddled with the ideas that would eventually molt into Tarkovsky’s future six feature films, a diminutive career (seven including this film) by any standards, Ivan’s Childhood lays the groundwork for Tarkovsky’s unmooring of the cinematic consciousness into realms both indescribably beautiful and thoughtfully revelatory. Then again, “eventually” doesn’t do justice to Ivan’s impossible grandeur and fractured intimacy; on its own terms, had the greatest director of the last fifty years not pursued a career in film at all and absconded from sight leaving only this singular mark of his trespass on our earthly realm, he would still be one of the definitive directors of the second half of the twentieth century. Continue reading