I was planning on curbing my tendency to upload two reviews every week for Midnight Screenings, rather than one, but seeing as how I missed last week’s review, I’ll post two this week one last time. One is below, with another, linked by theme and something a bit more concrete, to come tomorrow.

I was planning on curbing my tendency to upload two reviews every week for Midnight Screenings, rather than one, but seeing as how I missed last week’s review, I’ll post two this week one last time. One is below, with another, linked by theme and something a bit more concrete, to come tomorrow.

Update June 2019: After another rewatch, I remain enamored of Lynch’s general aura of cinematic discontent, and even more enamored of his obvious empathy for (most of) his characters: the American dreams that Lynch devours whole-cloth are, of course, his own dreams, and Blue Velvet in particular has the unmistakable mood of possibility thoroughly deflated, of Lynch’s own innocence curdled into demonic cynicism. Lynch’s immanent critique of mid-century Hollywood cinema and the dreams it promised feels less like an outsider director dismembering a naive vision he feels foreign to (and thus one he views as deluded) than the tragically absurd sight of an animal devouring itself from behind. For that reason, the film’s mood is not of barking cynicism but elegiac collapse, a dream realizing that it cannot sustain itself after all.

Still, after having done more of a deep dive into Lynch in the ensuing five years, Blue Velvet does feel slightly … cruder this time out. It’s fantastic cinema, and in 1986 it must have felt like an apocalyptic full-frontal onslaught, but after three (on-and-off) decades of Lynch so thoroughly burrowing into and then disemboweling everyday life and the cinema that upholsters it, one can’t help but think of Blue Velvet as a test-run for Wild at Heart, or a cinematic prelude to Twin Peaks, to say nothing of the sheer depths of cinematic exploration he would achieve with Mulholland Drive. His elastic attitude toward aesthetics – many images evoke demented horror, mournful drama, and tortured comedy at the same time – is as phenomenal as ever. But Blue Velvet feels a bit more schematic in its analysis – many of the visual contrasts are explicitly schematic, for that matter – and less of a maddened dispatch from another world (that is, of course, the underbelly of our world) that exposes the soul-devouring undercurrents of a reality totally riven before our eyes. It’s the only one of Lynch’s mature (which is to say, Blue Velvet onwards) features that feels like he’s already worked everything out in his head before filming, and that robs the film of Lynch’s typical aura of having discovered modernity unraveling itself mid-process.

Original Review:

Blue Velvet is curiously, even paradoxically, both director David Lynch’s most anarchic film and one of his most straightforward. Perhaps the two are linked, for Lynch opens up the film with an image of straightforward reality he spends the film taking to task. We get clean-cut grass and well-manicured houses, spaced evenly between one another, hiding well-manicured people who probably take pains to space themselves evenly as well. Lynch is aware that these images construct our dreams of America, or at least our dreams of an American past, and even in his admitted celebration of them, he also examines them, cutting into them like a knife through pre-sliced, packaged white bread (what could be more American?) hiding maggots under its façade of comfort. Continue reading →

Note: this review is something of a repurposed college-age article, so be kind to the writing…

Note: this review is something of a repurposed college-age article, so be kind to the writing…

Updated mid-2017

Updated mid-2017 A question: Have you ever seen a movie that made you want so furiously to scribble down notes about its greatness while watching that you were actually annoyed that it kept you looking at the screen with its unapologetic greatness to the point of being unable to write anything down legibly? I ask in this form, of course, because naturally I’m only writing to people who would want to write down notes about movies while watching. Everyone else who could conceivably see this film will probably be turned off by how garishly oppressive and gloriously messy it is to have any interest in reading this. And they’d be completely right too, but I still like the film anyway.

A question: Have you ever seen a movie that made you want so furiously to scribble down notes about its greatness while watching that you were actually annoyed that it kept you looking at the screen with its unapologetic greatness to the point of being unable to write anything down legibly? I ask in this form, of course, because naturally I’m only writing to people who would want to write down notes about movies while watching. Everyone else who could conceivably see this film will probably be turned off by how garishly oppressive and gloriously messy it is to have any interest in reading this. And they’d be completely right too, but I still like the film anyway. Edited

Edited I was planning on curbing my tendency to upload two reviews every week for Midnight Screenings, rather than one, but seeing as how I missed last week’s review, I’ll post two this week one last time. One is below, with another, linked by theme and something a bit more concrete, to come tomorrow.

I was planning on curbing my tendency to upload two reviews every week for Midnight Screenings, rather than one, but seeing as how I missed last week’s review, I’ll post two this week one last time. One is below, with another, linked by theme and something a bit more concrete, to come tomorrow. Edited

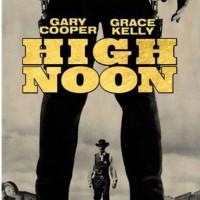

Edited.jpg) I’ve seen a lot of Westerns. I actively seek out the genre for two reasons. Firstly, existing within a genre of B-pictures with lesser commercial prospects, the films often have a freedom to poke and prod at the nature of film and storytelling in ways films with more money put into them, and thus with more money expected in return, might not have the unexpected freedom for. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the Western was historically perhaps the genre where America and its desires are most wont to play themselves out for audiences. Westerns explore a mythic version of traditional American life – some uphold it, some read it past itself to create untold postmodern myths, and some take a knife to the genre and skewer it for all to see.

I’ve seen a lot of Westerns. I actively seek out the genre for two reasons. Firstly, existing within a genre of B-pictures with lesser commercial prospects, the films often have a freedom to poke and prod at the nature of film and storytelling in ways films with more money put into them, and thus with more money expected in return, might not have the unexpected freedom for. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the Western was historically perhaps the genre where America and its desires are most wont to play themselves out for audiences. Westerns explore a mythic version of traditional American life – some uphold it, some read it past itself to create untold postmodern myths, and some take a knife to the genre and skewer it for all to see.  Early period westerns aren’t exactly the most realistic of films, nor are they known to be among the most original either, and with good reason. Pre-1960s Westerns often follow suit with their fore-bearers, seemingly content to present the story of the nameless drifter or the fastidious and courageous lawmen who saves the damsel in distress from villains that fall somewhere between Snidely Whiplash and Genghis Khan. There’s bound to be a shootout or two, and chances are good that one may feature the characters suddenly rushing to fit into place on the cue of a clock striking…ahem…high noon. Thank you, thank you. Many of these films also happen to be masterpieces of fable-like proportions, playing less like nuanced reality than a collective dream of a time long-gone. They work like bed-time stories we tell ourselves to ward away the evil spirits of icky things, which, unfortunately, included progress and modernity to those who often watched the films.

Early period westerns aren’t exactly the most realistic of films, nor are they known to be among the most original either, and with good reason. Pre-1960s Westerns often follow suit with their fore-bearers, seemingly content to present the story of the nameless drifter or the fastidious and courageous lawmen who saves the damsel in distress from villains that fall somewhere between Snidely Whiplash and Genghis Khan. There’s bound to be a shootout or two, and chances are good that one may feature the characters suddenly rushing to fit into place on the cue of a clock striking…ahem…high noon. Thank you, thank you. Many of these films also happen to be masterpieces of fable-like proportions, playing less like nuanced reality than a collective dream of a time long-gone. They work like bed-time stories we tell ourselves to ward away the evil spirits of icky things, which, unfortunately, included progress and modernity to those who often watched the films.

Edited

Edited