Bob Rafelson’s television career came to a head with 1968 Head, a wonderfully parentless concoction of off-kilter artifice and cinema verite absurdity from the halcyon days of the New Hollywood and the waning post-mortem of the psychedelic ’60s. Pitched at the intersection of the two decades, Head is a blissful concoction of hyperactive mania belying serious, doleful interrogation, a film that uses avant-garde channel-surfing as a way to embody the existential homelessness of life at the end of the 1960s. Like the apocalyptic fallout from a decade-long acid trip, its anti-continuity editing mechanics pushed the decade’s assertion of living for the moment to consternated heights where any human ability to consider the future was laughed at by the bedlam of a world where simple notions of time and place were rapidly unwinding in front of America’s eyes. Bob Rafelson’s introduction to the film world, still his secret weapon and best film, suggests the death spasm of hippie culture keel-hauled into psychotropic madness. Continue reading

Bob Rafelson’s television career came to a head with 1968 Head, a wonderfully parentless concoction of off-kilter artifice and cinema verite absurdity from the halcyon days of the New Hollywood and the waning post-mortem of the psychedelic ’60s. Pitched at the intersection of the two decades, Head is a blissful concoction of hyperactive mania belying serious, doleful interrogation, a film that uses avant-garde channel-surfing as a way to embody the existential homelessness of life at the end of the 1960s. Like the apocalyptic fallout from a decade-long acid trip, its anti-continuity editing mechanics pushed the decade’s assertion of living for the moment to consternated heights where any human ability to consider the future was laughed at by the bedlam of a world where simple notions of time and place were rapidly unwinding in front of America’s eyes. Bob Rafelson’s introduction to the film world, still his secret weapon and best film, suggests the death spasm of hippie culture keel-hauled into psychotropic madness. Continue reading

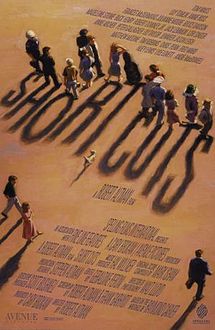

Film Favorites: Short Cuts

The 1980s were like forced, unpaid indefinite leave for the more challenging American directors to emerge out of the 1970s New Hollywood Cinema. Martin Scorsese mostly survived the war on adult-minded cinema. Terrence Malick just up and left, emerging at the tail end of the more independent ’90s in a nominally less hostile climate to his kind. One of the most productive casualties of the ’80s was Robert Altman, a director who pumped out smaller-scale projects like a worker-ant throughout the decade, even if few of them were buttressed by critical or commercial support. 1992’s The Player, a surprising and ceremonious return to commercial and critical success for Altman, was a ribald, scabrous affair but hardly a darling work of formalism to match any number of films Altman directed during the ’70s. Notable though that film may be, its most lasting and important achievement is more utilitarian: it brought Altman back from the nebulous ether, and afforded him the clout to make the far more intellectually provocative, cinematically daring Short Cuts. Continue reading

The 1980s were like forced, unpaid indefinite leave for the more challenging American directors to emerge out of the 1970s New Hollywood Cinema. Martin Scorsese mostly survived the war on adult-minded cinema. Terrence Malick just up and left, emerging at the tail end of the more independent ’90s in a nominally less hostile climate to his kind. One of the most productive casualties of the ’80s was Robert Altman, a director who pumped out smaller-scale projects like a worker-ant throughout the decade, even if few of them were buttressed by critical or commercial support. 1992’s The Player, a surprising and ceremonious return to commercial and critical success for Altman, was a ribald, scabrous affair but hardly a darling work of formalism to match any number of films Altman directed during the ’70s. Notable though that film may be, its most lasting and important achievement is more utilitarian: it brought Altman back from the nebulous ether, and afforded him the clout to make the far more intellectually provocative, cinematically daring Short Cuts. Continue reading

Must all Reviews have a Reason?: Full Metal Jacket

A review apropos of nothing in particular…

A review apropos of nothing in particular…

The resurgence of Full Metal Jacket in Stanley Kubrick’s inimitable oeuvre arises, perhaps necessarily, in similitude with society eschewing Kubrick more generally. As the cryptic, obstreperous director wanes, his forgotten films wax. With this shift, valuable discoveries abound in a film that was largely manhandled and left for the scrap heap upon its initial release. But just because a film leaves breadcrumbs for the picking doesn’t mean it is a full feast. Valuate Full Metal Jacket, cinematic minds ought to. But it should not be sacrosanct. A simple comparison to the films released on either side of it reveals Full Metal Jacket to be a wanting trough in between two peaks of modern Western cinema. Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket is an incisive film, but hardly the singular competition-vanquishing achievement that many now proclaim it to be. Continue reading

Progenitors: Lost Highway

With Triple Nine looking all vaguely neo-noirish and me having already reviewed director John Hillcoat’s notable films, I’ve decided to look at a handful of films from the last heyday of the neo-noir: the 1990s. And of course David Lynch …

With Triple Nine looking all vaguely neo-noirish and me having already reviewed director John Hillcoat’s notable films, I’ve decided to look at a handful of films from the last heyday of the neo-noir: the 1990s. And of course David Lynch …

David Lynch’s Lost Highway begins with a paragon of the untrammeled cinematic id. As the pulpy, pop-fried credits announce themselves on the screen like pugnacious fighting words from the darkest bowels of Lynch’s gut, the camera hurtles on a forward trajectory to hell itself, a slithery, avant-garde David Bowie melody doing violence to the darkness of the screen before us. This is the noir expunged of propriety, excised from the surface level world and headed straight to the dustbin of male inadequacy. Continue reading

Progenitors: Hard Eight

With Triple Nine looking all vaguely neo-noirish and me having already reviewed director John Hillcoat’s notable films, I’ve decided to look at a handful of films from the last heyday of the neo-noir: the 1990s. I wish I hadn’t already reviewed Seven, because then I could really pull a “seven, eight, nine” joke right about now. Oh well.

With Triple Nine looking all vaguely neo-noirish and me having already reviewed director John Hillcoat’s notable films, I’ve decided to look at a handful of films from the last heyday of the neo-noir: the 1990s. I wish I hadn’t already reviewed Seven, because then I could really pull a “seven, eight, nine” joke right about now. Oh well.

Paul Thomas Anderson loves him some Robert Altman, and he damn sure wants you to know it. Boogie Nights is his Nashville, Magnolia his Short Cuts, There Will Be Blood his McCabe & Mrs. Miller, and Inherent Vice his The Long Goodbye. Both directors are united in their attenuation to social ennui and their sweltering pop fantasia takes on the perils of American fiction and everyday life propelled on the back of scorching camera motions (Magnolia’s most famous sequence plays like a cocaine nightmare version of Altman’s prodigious love of zooming his camera into every nook and cranny of the Earth he could overturn). Continue reading

Progenitors: Red Rock West and Kiss of Death

With Triple Nine looking all vaguely neo-noirish and me having already reviewed director John Hillcoat’s notable films, I’ve decided to look at a handful of films from the last heyday of the neo-noir: the 1990s. Of course, because it is the 1990s, we must begin with two Nicolas Cage vehicles, as you do.

With Triple Nine looking all vaguely neo-noirish and me having already reviewed director John Hillcoat’s notable films, I’ve decided to look at a handful of films from the last heyday of the neo-noir: the 1990s. Of course, because it is the 1990s, we must begin with two Nicolas Cage vehicles, as you do.

Red Rock West

John Dahl’s minimalist Norman Rockwell fetish is nourished with a gleefully off-hand, almost accidental energy in the duplicitous Red Rock West, a film that stars Nicolas Cage, Lara Flynn Boyle, and Dennis Hopper and fittingly recalls by turn the giddy Americana of Raising Arizona, the scathing post-modernism of Twin Peaks, and the anti-social inside-out small-town throat-grab of Blue Velvet.

When Cage’s character saunters into a Wyoming town in search of a job that just won’t coalesce, fortune turns against him and the decrepit rot and turpitude of rural American bite back. After all, in the type of town where everyone knows everyone, you can’t really hide. In this perverted Western landscape, the very idea of “heading out West” is upended and downtuned, besieged by more than a modicum of deceit and turmoil chiffonading the American Dream into enough mincemeat to fill Monument Valley itself. For a sepulcher to forgotten dreams, it’s a hoot, and the cemetery of a forest that engulfs the town of Red Rock at night ain’t half bad either.

Admittedly, Dahl doesn’t strike a chord as a natural born genius, but he’s a sharp enough tack and a journeyman of palpable suspense and playful subtext, most notably when he undoes the largesse-laden Texas drawl of Cage’s character at the seams. This laconic, pulpy film coils like a writhing king snake but it manages to accrue nervous energy without the accompanying nosebleed of solemnity or self-imposed meaning. In fact, Dahl’s wry comedic edge delights in letting us know how precipitous the film is, how rough-around-the-edges its denim-clad drifter of a yarn may be; it’s as if it’s being constructed before our very noses. Rather archly, it contorts the noir tradition of chance begetting bad habits by finding the light for Cage’s character in chance itself. Luck enjoins the story into motion, and luck concludes it. Cage is just wandering through, writing notes that no one believes and sliding into easy lies that everyone does.

Score: 8/10

Kiss of Death

Kiss of Death

One of the strangest films to ever appear at the Cannes film festival, Kiss of Death is a neo-noir that isn’t quite dressed to kill, but it at least has one pant-leg on, even when it’s tripping over it. Lead man David Caruso is a wet blanket, Helen Hunt is waddling around in neutral, and the screenplay is less a movie than a murderer’s row of fascinating scenes loosely tethered together in the same room. But, accident or not, Kiss of Death stumbles into its fair share of oddball menace and mendacity.

Barbet Schroeder is a capable stylist but no auteur, and viewed through the lens of 1995 with heavy-hitters like Seven, Devil in a Blue Dress, and Fargo rattling or skulking into theaters on either side of it, Kiss of Death definitely feels outclassed amidst the competition. But with vociferous neo-noirs less thick-on-the-ground these days, one can appreciate Kiss of Death’s more modest pleasures, some of which relate to Schroeder’s agreeably strangulating tone and acrid arctic blue chills. The film doesn’t really coagulate the neo-noir atmosphere it so clearly pines for; the bizarrely over-lit hues accrue a pop-fried thriller sensibility instead, which is somewhere between a lateral trade and a slight step-down. Puckering up the piece with zest and zing are molotov cocktails hurled by a motor-mouthed Michael Rapaport, a slithering Stanley Tucci, and a weathered but hectoring Samuel Jackson. There’s a whole menagerie of incandescent, peppery energy twirling around the edges here.

Plus, Kiss of Death boasts an injection by an inspiringly cocaine-addled Nicolas Cage on the eve of winning an Oscar and diving headfirst into leading man status that would quickly turn his entire career into a toxic cloud of vacillating insufferable and endearing inanity of the first order. Excise Cage’s scenes for your own film a you can see a twinkle in Werner Herzog’s eye, fulfilled a decade and a half later with the vastly underrated Bad Lieutenant sequel.

Score: 6/10

Progenitors: Roman Polanski’s Macbeth

Having finally caught up with Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth, I decided to take a look at the cinematic version it owes itself most readily to.

Having finally caught up with Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth, I decided to take a look at the cinematic version it owes itself most readily to.

The appeal of Roman Polanski’s earliest films is much the same appeal of Emily Dickinson’s lust-stabbed poetry: sheer, giddy brokenness. Like Dickinson’s disturbed capriciousness and orgasmic hyphens that sever the natural rhythm and flow of normal meter and sane minds, Roman Polanski’s early films come to us spastically, errantly strewn about as bits and morsels and shattered carcasses stricken across the land. The corrective tissues appear almost nonexistent, the cartilage lost to time and unstitched. His early films are cinema without forebears, with ’70s grotto smashed into the theatrical slabs of pre-modern cinema Polanski adored quietly but no less vociferously than the haute couture modernism en vogue during his era. Watching Cul-de-Sac or Knife in the Water is like watching an uneasy mind of clamorously clashing style and unfixed pre, post, and midsexual urges vacillating all about over the canvas without inhibition. Continue reading

Film Favorites: Voyage to Italy

The neorealist corpuses of Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini – comrades in arms, yes, but figures whose similitude belies discrepancies in their works – have been cordoned off into the same space for so long you half forget they were actually different filmmakers at all. Yet De Sica’s world of omnipresent off-screen space maundering around the edges of open frames only shares partial similarities with Rossellini’s works. What both filmmakers did unite under was a continual, restive thrust not to rest on singular definitions of neorealism, an insatiable desire to experiment with, and critique, the style that made them household names among connoisseurs of world cinema. Continue reading

The neorealist corpuses of Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini – comrades in arms, yes, but figures whose similitude belies discrepancies in their works – have been cordoned off into the same space for so long you half forget they were actually different filmmakers at all. Yet De Sica’s world of omnipresent off-screen space maundering around the edges of open frames only shares partial similarities with Rossellini’s works. What both filmmakers did unite under was a continual, restive thrust not to rest on singular definitions of neorealism, an insatiable desire to experiment with, and critique, the style that made them household names among connoisseurs of world cinema. Continue reading

Review: Macbeth

Generally speaking, the most striking cinematic Shakespeares are those that are the most strikingly cinematic. As a rule, hewing close to the stagebound play is a recipe for neutralization when delivered in a cinematic vessel. I wish no schadenfreude upon the Shake man himself, but arrant verbosity in a visual medium, especially in an adaptation of a play, is a harbinger only of a filmmaker’s belief that the almighty play is sacrosanct and immutable. A real artist instead uses the broad strokes to unpack the play as a palimpsest with lingering vestiges of theatrical memory interacting with modern themes and motifs to construct something new, bold, and visionary. If you love something, leave (most of) it alone. Pick out the necessities and find a new voice, your own voice, with it. Continue reading

Generally speaking, the most striking cinematic Shakespeares are those that are the most strikingly cinematic. As a rule, hewing close to the stagebound play is a recipe for neutralization when delivered in a cinematic vessel. I wish no schadenfreude upon the Shake man himself, but arrant verbosity in a visual medium, especially in an adaptation of a play, is a harbinger only of a filmmaker’s belief that the almighty play is sacrosanct and immutable. A real artist instead uses the broad strokes to unpack the play as a palimpsest with lingering vestiges of theatrical memory interacting with modern themes and motifs to construct something new, bold, and visionary. If you love something, leave (most of) it alone. Pick out the necessities and find a new voice, your own voice, with it. Continue reading

Midnight Screenings: The Howling

Writer-director Joe Dante is pop culture dead weight today, but in the mid ’80s he was the zeitgeist. A progenitor to the highfalutin sub-horror irony of Scream and a cornucopia of too-scared-to-admit-they-are-horror films in the intensely glib world of ’00s horror, Dante’s brand of irony was much less prone to the fraudulence of incessant hedging. His earliest films, Piranha and The Howling, upend horror tradition without fecklessly resorting to ingratiating pleadings of blasé, sycophantic self-superiority. They rib and tickle, but they’re also honest-to-god horror films, as marinated in tenebrous cinematography and bone-rattling sound as any films of their time. They tease us, but they do not trick us: they mean what they say, and they bite. Continue reading

Writer-director Joe Dante is pop culture dead weight today, but in the mid ’80s he was the zeitgeist. A progenitor to the highfalutin sub-horror irony of Scream and a cornucopia of too-scared-to-admit-they-are-horror films in the intensely glib world of ’00s horror, Dante’s brand of irony was much less prone to the fraudulence of incessant hedging. His earliest films, Piranha and The Howling, upend horror tradition without fecklessly resorting to ingratiating pleadings of blasé, sycophantic self-superiority. They rib and tickle, but they’re also honest-to-god horror films, as marinated in tenebrous cinematography and bone-rattling sound as any films of their time. They tease us, but they do not trick us: they mean what they say, and they bite. Continue reading