One doesn’t exactly go into a “Victor Fleming Production” and expect a kind of trashy wail covered in barbed wire. And one doesn’t get it with Red Dust, but it still feels like a specter from another world, the Pre-Code Hollywood world to be exact. In stark contrast to his one-two Gone with the Wind, Wizard of Oz punch in the most golden of Hollywood’s gilded years, 1939, the trim, rough-housed Red Dust never aspires to greatness, and as such, it is never strangled by an imaginative affinity with histrionic hyperbole run amok (the latter mode being MGM’s most cherished tone). Instead, this earthy, husky MGM film is a vortex of lusty, vulgar brashness and disreputable puncture wounds. Unfortunately, though, it’s all haunted over by the never-ending specter of colonialism in an Orientalist world authored by the West to serve as a presentational backdrop, even a manicured garden, for white subjects to battle out their own individual problems while towering over darker faces that are little more than part of the museum-quality scenery. I suppose you can’t change everything that was part of the conservative MGM claw. Continue reading

One doesn’t exactly go into a “Victor Fleming Production” and expect a kind of trashy wail covered in barbed wire. And one doesn’t get it with Red Dust, but it still feels like a specter from another world, the Pre-Code Hollywood world to be exact. In stark contrast to his one-two Gone with the Wind, Wizard of Oz punch in the most golden of Hollywood’s gilded years, 1939, the trim, rough-housed Red Dust never aspires to greatness, and as such, it is never strangled by an imaginative affinity with histrionic hyperbole run amok (the latter mode being MGM’s most cherished tone). Instead, this earthy, husky MGM film is a vortex of lusty, vulgar brashness and disreputable puncture wounds. Unfortunately, though, it’s all haunted over by the never-ending specter of colonialism in an Orientalist world authored by the West to serve as a presentational backdrop, even a manicured garden, for white subjects to battle out their own individual problems while towering over darker faces that are little more than part of the museum-quality scenery. I suppose you can’t change everything that was part of the conservative MGM claw. Continue reading

Review: The Neon Demon

As with his entire oeuvre, Nicolas Winding Refn’s newest vision of pain and beauty is more or less redolent, but redolence – like flesh, the film argues – is a currency that can be nastily enticing in the fevered perceptions it affords for, even if you hate yourself in the morning. In this case, he’s taking his latent Dario Argento fetish out of the crawlspace, giving the blood-curdling red overtones a hard corporate sear to create a grotesquely synthetic construct, throwing the mise-en-scene into tangles of negative space and rattling aural alchemy courtesy of Cliff Martinez, and giving audiences either the sanguinarium or the dull ritual they’ve already decided the film represents beforehand. Continue reading

As with his entire oeuvre, Nicolas Winding Refn’s newest vision of pain and beauty is more or less redolent, but redolence – like flesh, the film argues – is a currency that can be nastily enticing in the fevered perceptions it affords for, even if you hate yourself in the morning. In this case, he’s taking his latent Dario Argento fetish out of the crawlspace, giving the blood-curdling red overtones a hard corporate sear to create a grotesquely synthetic construct, throwing the mise-en-scene into tangles of negative space and rattling aural alchemy courtesy of Cliff Martinez, and giving audiences either the sanguinarium or the dull ritual they’ve already decided the film represents beforehand. Continue reading

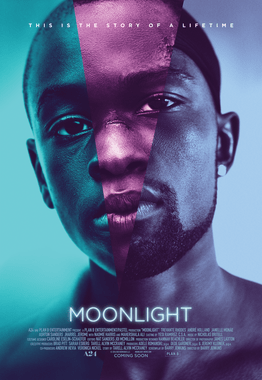

Review: Moonlight

“Indie Darling” is a phrase best approached with caution in an era where the plague of the quasi-naturalist (read: twee) Sundance aesthetic has only claimed more victims with each passing year. Of course, Moonlight is a Telluride darling, a fact that tells us essentially nothing (Telluride is neither as consistently middlebrow as Sundance nor as unilaterally experimental and anarchic as Cannes). And being told nothing for this quiet, starlight wonder is for the best. This project, written and directed by Barry Jenkins, invokes some of the rhythms of a hip, cosmopolitan, aggressively fashionable independent production for which “important subject matter” is considered a fitting replacement for craft or aesthetic. Yet Jenkins’ film, which constantly and wonderfully eludes stable meaning, is – mostly for the better – a more omnivorous, piecemeal production than most “social issue” films, a work of stylistic collision and collusion rather than a monolithic one-size-fits-all aesthetic. Continue reading

“Indie Darling” is a phrase best approached with caution in an era where the plague of the quasi-naturalist (read: twee) Sundance aesthetic has only claimed more victims with each passing year. Of course, Moonlight is a Telluride darling, a fact that tells us essentially nothing (Telluride is neither as consistently middlebrow as Sundance nor as unilaterally experimental and anarchic as Cannes). And being told nothing for this quiet, starlight wonder is for the best. This project, written and directed by Barry Jenkins, invokes some of the rhythms of a hip, cosmopolitan, aggressively fashionable independent production for which “important subject matter” is considered a fitting replacement for craft or aesthetic. Yet Jenkins’ film, which constantly and wonderfully eludes stable meaning, is – mostly for the better – a more omnivorous, piecemeal production than most “social issue” films, a work of stylistic collision and collusion rather than a monolithic one-size-fits-all aesthetic. Continue reading

Films for Class: The Grapes of Wrath

Seventy-six years on, The Grapes of Wrath’s star has faded noticeably, but it’s hardly been marginalized to the corners of cinematic history, even if the film explores the perverse marginalization of the American populace and the necrotization of an American dream mutilated beyond recognition. One would be surprised if a student of cinema meaningfully preferred this Best Picture winner over director John Ford’s masterful prior film, 1939’s Stagecoach (the best film from what many consider the most important year in American cinema, but that’s a story for another time). Hell, a thoughtful formalist might even prefer Ford’s next film, the frequently marginalized How Green Was My Valley (it’s no Citizen Kane, but what film is?). Still, square as it may be compared to the rebellious upstarts of the ‘70s and the hip young things of the American independent movement in the ‘50s, Ford’s incomparable skill for marshaling the formal principles of cinema for tales of plain-spoken, relatively unromantic Romanticism was usually untouched in the Classical era. If The Grapes of Wrath isn’t actually close to the apex of his career, it’s a sturdy and lyrical, if hardly revelatory, tapestry all the same. Continue reading

Seventy-six years on, The Grapes of Wrath’s star has faded noticeably, but it’s hardly been marginalized to the corners of cinematic history, even if the film explores the perverse marginalization of the American populace and the necrotization of an American dream mutilated beyond recognition. One would be surprised if a student of cinema meaningfully preferred this Best Picture winner over director John Ford’s masterful prior film, 1939’s Stagecoach (the best film from what many consider the most important year in American cinema, but that’s a story for another time). Hell, a thoughtful formalist might even prefer Ford’s next film, the frequently marginalized How Green Was My Valley (it’s no Citizen Kane, but what film is?). Still, square as it may be compared to the rebellious upstarts of the ‘70s and the hip young things of the American independent movement in the ‘50s, Ford’s incomparable skill for marshaling the formal principles of cinema for tales of plain-spoken, relatively unromantic Romanticism was usually untouched in the Classical era. If The Grapes of Wrath isn’t actually close to the apex of his career, it’s a sturdy and lyrical, if hardly revelatory, tapestry all the same. Continue reading

Reviews: The Magnificent Seven and Don’t Breathe

The Magnificent Seven

The Magnificent Seven

Comparing a film to its predecessor is an exercise in defeat and dredging up the past when the present is here for us to intake on its own. Besides, with The Magnificent Seven, it doesn’t really get us anywhere; “seven fighters protect villagers from bad stuff” isn’t exactly robust enough a concept to qualify as a specific, remake-able object or a debt owed from one film to another. It’s more like a mythology passed down through generations. What makes the 2016 The Magnificent Seven’s amorphous scrawl a fumble more than a rumble (I couldn’t resist) is its own doing, irrespective of its forebears or any questions about “adaptation”. One doesn’t have to watch the 1960 film to see how feather-light the attempts to catalyze a parched throat are in this new one. Or the inchoate, failed efforts to germinate camaraderie in this supposed family affair. The mediocrities are on the screen, and they speak for themselves. The song is fine, but the cover is weightless. It’s dry-bones competence, well filmed in the “I guess so” sense. But Fuqua’s film – in what is quickly becoming an almost auteurist tick of his – is habitually addicted to being the most mediocre version of itself it can possibly be. Continue reading

Reviews: Shin Godzilla and Ip Man 3

Shin Godzilla

Shin Godzilla

Reduced but by no means relaxed, Japan’s return to the land of the fire breathing lizard after a twelve year sabbatical (where we’ve had to turn to South Korea for astounding East Asian genre fare) is a mixture of the high impact and the low key. Annulling the decades of tomfoolery and allegiance to matinee thrills that has infected the franchise, Shin revives the thunder lizard as a cantankerous, almost unknowable beast capable of unsublimated dispassion for the human race. Shin Godzilla is a work about the depletion of humanity that also, as ancillary achievement, depletes the gee-willickers Saturday morning routines plaguing most monster movies throughout history (from any nation). For this new film, think hysteria, but of the perverse, unhinged original-definition kind where the recesses of the mind are fodder for some destructive unclassifiable force. Continue reading

Films for Class: Yo Soy Cuba

Crying foul on director Mikhail Kalatozov’s deliriously unhinged, masterful slice of post-Bay of Pigs agitprop for its unapologetic commitment to ideology would be tantamount to artistic heresy and limpid emphasis on the political over the artistic if the film weren’t such a bold and brazen reclamation of that age-old fact that art is innately political no matter what. Plunging into the revelry of fantastical space as obviously euphoric as Lang’s Metropolis city was demonic, and as bodaciously animated as Lang’s vision to boot, Yo Soy Cuba is an aesthetic vision primarily. But with these aesthetics, the proof is in the proverbial politics to begin with. Separating this far-out vision of a largely fictive representation of Cuban life from its animated muse – its Soviet morality – is at some level impossible: like Eisenstein’s utilization of montage to stage ideas of collective conflict, cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky’s aesthetic revolutions aren’t apolitical. Yo Soy Cuba is a vivacious workout, a Communist high palpably star-struck by the wave of political revolution it presumed (or hoped) was on the horizon, a film bathed in all the passions genuine belief can muster, and a work that marshals an unmediated, even crazed support for Cuban life into a catalyst for unbridled cinematic experimentation positively running wild with screw-loose charisma. Continue reading

Crying foul on director Mikhail Kalatozov’s deliriously unhinged, masterful slice of post-Bay of Pigs agitprop for its unapologetic commitment to ideology would be tantamount to artistic heresy and limpid emphasis on the political over the artistic if the film weren’t such a bold and brazen reclamation of that age-old fact that art is innately political no matter what. Plunging into the revelry of fantastical space as obviously euphoric as Lang’s Metropolis city was demonic, and as bodaciously animated as Lang’s vision to boot, Yo Soy Cuba is an aesthetic vision primarily. But with these aesthetics, the proof is in the proverbial politics to begin with. Separating this far-out vision of a largely fictive representation of Cuban life from its animated muse – its Soviet morality – is at some level impossible: like Eisenstein’s utilization of montage to stage ideas of collective conflict, cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky’s aesthetic revolutions aren’t apolitical. Yo Soy Cuba is a vivacious workout, a Communist high palpably star-struck by the wave of political revolution it presumed (or hoped) was on the horizon, a film bathed in all the passions genuine belief can muster, and a work that marshals an unmediated, even crazed support for Cuban life into a catalyst for unbridled cinematic experimentation positively running wild with screw-loose charisma. Continue reading

Films for Class: His Girl Friday

Simultaneously reaching a near artistic zenith and floundering in middling commercial anonymity with the giddy, off its rocker, positively deranged Bringing Up Baby in 1938, director Howard Hawks had obviously caught an itch that could not be quelled by merely retreating to a new genre (although Hawks was one of the foremost masters of genre-agnosticism in film history). Conscripting the dastardly trio of Charles Lederer, Ben Hecht, and Charles MacArthur to whip up a whirlygust of a screenplay conjured from the bones of the stageplay The Front Page (by the latter two of the trio), Hawks required another at bat for the genre. The progeny of this attempt, His Girl Friday, isn’t inherently the best Hawks film (it isn’t even the best Hawks screwball in my estimation). But as his second-chance screwball, it is the summit of his decade-long experimentation with the disconcerting, rebellious limits and possibilities of film sound. Continue reading

Simultaneously reaching a near artistic zenith and floundering in middling commercial anonymity with the giddy, off its rocker, positively deranged Bringing Up Baby in 1938, director Howard Hawks had obviously caught an itch that could not be quelled by merely retreating to a new genre (although Hawks was one of the foremost masters of genre-agnosticism in film history). Conscripting the dastardly trio of Charles Lederer, Ben Hecht, and Charles MacArthur to whip up a whirlygust of a screenplay conjured from the bones of the stageplay The Front Page (by the latter two of the trio), Hawks required another at bat for the genre. The progeny of this attempt, His Girl Friday, isn’t inherently the best Hawks film (it isn’t even the best Hawks screwball in my estimation). But as his second-chance screwball, it is the summit of his decade-long experimentation with the disconcerting, rebellious limits and possibilities of film sound. Continue reading

Films for Class: Scarface

An aberration of the soon-to-be-implemented, puritanical Hays Code, Howard Hawks’ twitchy, rough-housed Scarface is a coarse rampage of firebrand cinematic verve, a sojourn into the underworld and death that paradoxically and perversely reflects cinema at its liveliest. Early sound cinema is often (falsely) denied vitality and dismissed as stodgy, but Scarface has a bullet or two to quell those who would deny it. Independently financed by Howard Hughes, Scarface trumpets its independent spirit as an ambivalently trashy social expose that wears its heart and its brain on its pistol. Cinema in the raw, it displays casual mastery of technique but invokes the shambolic one-take sloppiness of a killer Neil Young album. Continue reading

An aberration of the soon-to-be-implemented, puritanical Hays Code, Howard Hawks’ twitchy, rough-housed Scarface is a coarse rampage of firebrand cinematic verve, a sojourn into the underworld and death that paradoxically and perversely reflects cinema at its liveliest. Early sound cinema is often (falsely) denied vitality and dismissed as stodgy, but Scarface has a bullet or two to quell those who would deny it. Independently financed by Howard Hughes, Scarface trumpets its independent spirit as an ambivalently trashy social expose that wears its heart and its brain on its pistol. Cinema in the raw, it displays casual mastery of technique but invokes the shambolic one-take sloppiness of a killer Neil Young album. Continue reading

Films for Class: Frankenstein

In the early golden years of classical Hollywood, Universal Studios somehow always tempted, and summarily avoided, being left hanging in the lurch. Unlike the five major studios, all of which owned their own theaters and thus guaranteed distribution of their films, Universal wasn’t born with a silver spoon in its mouth. The spendthrift glamour of the MGM musical machine was but a cloudy daydream for a studio that, while hardly poverty row, needed to carve out its own niche to go toe to toe with the big boys. Rather than trying to assimilate to the studio heavies with facsimiles of their Dream Factory productions, Universal ensconced itself in the out-of-the-way places, the boondocks of cinema, testing out more unsavory realms befitting their more hardscrabble existence. Unwilling, or unable, to lull the masses with luxuriant A-picture opulence, the company decided not to soothe America to bed but to lower itself into the murk of mutated German Expressionism and raise a shrieking countermelody, the kind of rattling cadence that could wake the dead.

In the early golden years of classical Hollywood, Universal Studios somehow always tempted, and summarily avoided, being left hanging in the lurch. Unlike the five major studios, all of which owned their own theaters and thus guaranteed distribution of their films, Universal wasn’t born with a silver spoon in its mouth. The spendthrift glamour of the MGM musical machine was but a cloudy daydream for a studio that, while hardly poverty row, needed to carve out its own niche to go toe to toe with the big boys. Rather than trying to assimilate to the studio heavies with facsimiles of their Dream Factory productions, Universal ensconced itself in the out-of-the-way places, the boondocks of cinema, testing out more unsavory realms befitting their more hardscrabble existence. Unwilling, or unable, to lull the masses with luxuriant A-picture opulence, the company decided not to soothe America to bed but to lower itself into the murk of mutated German Expressionism and raise a shrieking countermelody, the kind of rattling cadence that could wake the dead.

Continue reading