This review published, belatedly, in memoriam of the death of animator Tyrus Wong at the ripe old age of 106.

This review published, belatedly, in memoriam of the death of animator Tyrus Wong at the ripe old age of 106.

Back in the halcyon days of early Disney Animation, the grandfatherly egomaniac at the acme of the company had not yet been exposed to the tumult of swaying company profits. (Or, at least, he had not yet developed any compunctions about doing what he wanted even if it was destined to fail at the box office). Still jejune in the animated feature film department, Disney was at this point a heart of a grand old moralist and an eye for galloping into new technological experience, both organs loosely stitched around a hard shell of a capitalist overlord who was not always sure how to mediate his personal artistry with the need for money in the American capitalistic tradition. This early era was bittersweet for Disney: his first masterpiece, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, a commercial monolith devouring all comers, was followed by three more masterpieces, all more adventurous, and all comparative (or outright) failures. Although Fantasia was his most personal casualty, the failure of Bambi no doubt seemed a malfeasance at the time. Barring Pinocchio, it is undoubtedly the most beautiful of all Disney feature-length films, and for his technical and even aesthetic radicalism, Disney was rewarded with the collective yawn of the unflinching, disinterested American public. Continue reading

This review published, belatedly, in memoriam of the death of author Richard Adams.

This review published, belatedly, in memoriam of the death of author Richard Adams.  Raoul Walsh’s cold-blooded reptile of a late-period gangster picture finally stills itself only when the genre reaches its apocalyptic acme in the death-scented denouement, the fumes permeating outward off the screen. Even when the credits crawl, the film refuses to be dismissed. The title doesn’t lie – shards and splinters of visual and sonic phosphorous sparkle right into your eyes with infectious charisma – but the punch and gusto are also counterpointed by chills of loneliness and murmurs of exhaustion. Released in 1949, White Heat evokes a genre’s last gasp, a style ready for a nervous breakdown, bracketing staccato bursts of violence to harried melancholia to disheveled, droll comedy. Gone is the wiry little slugger of star James Cagney’s youth found in the likes of The Public Enemy, replaced instead with a self-worrying work that examines its own rat-in-a-cage tempestuousness and ultimately embodies a missing link between Hawks’ Scarface and the downright pernicious onslaught to come in Bonnie and Clyde.

Raoul Walsh’s cold-blooded reptile of a late-period gangster picture finally stills itself only when the genre reaches its apocalyptic acme in the death-scented denouement, the fumes permeating outward off the screen. Even when the credits crawl, the film refuses to be dismissed. The title doesn’t lie – shards and splinters of visual and sonic phosphorous sparkle right into your eyes with infectious charisma – but the punch and gusto are also counterpointed by chills of loneliness and murmurs of exhaustion. Released in 1949, White Heat evokes a genre’s last gasp, a style ready for a nervous breakdown, bracketing staccato bursts of violence to harried melancholia to disheveled, droll comedy. Gone is the wiry little slugger of star James Cagney’s youth found in the likes of The Public Enemy, replaced instead with a self-worrying work that examines its own rat-in-a-cage tempestuousness and ultimately embodies a missing link between Hawks’ Scarface and the downright pernicious onslaught to come in Bonnie and Clyde.  George Cukor’s slightly creaky but undeniably spirited psychological thriller is quite a bit more “potboiler” than it is willing to admit until the Guignol denouement where the old fuss-and-stuff middle-of-the-road “please Knight me now” respectability of the diction and mise-en-scene pounces right into the ditch where it belongs. A B-picture in A-picture threads, it’s only when it unstitches its chest-caving corset that Gaslight finally has room to breathe. Which is to say: Gaslight is a little over-determined and too dignified in its prestige-pic wax to embrace the deliriously illicit trashiness at its core. (De Palma has essentially remade the film three dozen times, and while that statement may be hyperbole, how does one tackle De Palma without exaggeration?). Old Hollywood smut can be oh-so-gallant in its strewn-from-the-gutter and out-on-the-edge charisma when it just smacks some of that musty old regal upbringing right out of its properly-dictioned self. Yet Gaslight, while often killer, spent a little too much time in finishing school, dotting its I’s and crossing its T’s, and not enough time out on the streets learning how to play in the dirt where its heart truly lies.

George Cukor’s slightly creaky but undeniably spirited psychological thriller is quite a bit more “potboiler” than it is willing to admit until the Guignol denouement where the old fuss-and-stuff middle-of-the-road “please Knight me now” respectability of the diction and mise-en-scene pounces right into the ditch where it belongs. A B-picture in A-picture threads, it’s only when it unstitches its chest-caving corset that Gaslight finally has room to breathe. Which is to say: Gaslight is a little over-determined and too dignified in its prestige-pic wax to embrace the deliriously illicit trashiness at its core. (De Palma has essentially remade the film three dozen times, and while that statement may be hyperbole, how does one tackle De Palma without exaggeration?). Old Hollywood smut can be oh-so-gallant in its strewn-from-the-gutter and out-on-the-edge charisma when it just smacks some of that musty old regal upbringing right out of its properly-dictioned self. Yet Gaslight, while often killer, spent a little too much time in finishing school, dotting its I’s and crossing its T’s, and not enough time out on the streets learning how to play in the dirt where its heart truly lies.  A little old-timey cartoon before a feature for you all.

A little old-timey cartoon before a feature for you all. Chicken Little

Chicken Little I know the post is a little late, but at least I managed to watch these films on Halloween.

I know the post is a little late, but at least I managed to watch these films on Halloween.  I know the post is a little late, but at least I managed to watch these films on Halloween.

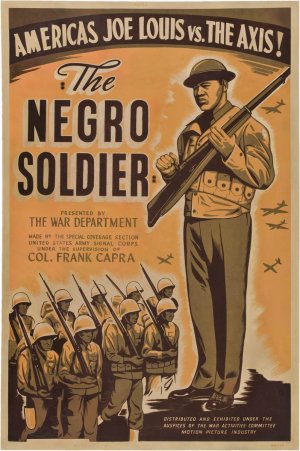

I know the post is a little late, but at least I managed to watch these films on Halloween.  Defanging the shroud of mystical primitivism cast over African-Americans while also recasting black America as the spiritual center of American modernity, The Negro Soldier is simultaneously mildly hat-tip-able and deeply troubling in its propagandistic ideological concoction of egalitarian American opportunity for even the darkest and most neglected among us. Of the Frank Capra school of not-untroubled but always plausible American possibility, The Negro Soldier is one of the more documented “Why We Fight”-adjacent films even seventy years later, and also among the more inescapably despicable in its morally compromising sanding-over of racially-fraught American history in the name of the kind of hermetically-sealed war-time inclusiveness that only exists … well, it only exist in the motion pictures, as they say. This is the American road to freedom, with no pothole large or oppressive enough for Capra not to blanket over in warmth and saccharine sweetness (of course, a blanket isn’t going to stop you from falling into the American nightmare of racism if you get a little too close to reality for Capra’s comfort). One wonders what hell the devil John Huston would have wrought for one of his wartime propaganda films…

Defanging the shroud of mystical primitivism cast over African-Americans while also recasting black America as the spiritual center of American modernity, The Negro Soldier is simultaneously mildly hat-tip-able and deeply troubling in its propagandistic ideological concoction of egalitarian American opportunity for even the darkest and most neglected among us. Of the Frank Capra school of not-untroubled but always plausible American possibility, The Negro Soldier is one of the more documented “Why We Fight”-adjacent films even seventy years later, and also among the more inescapably despicable in its morally compromising sanding-over of racially-fraught American history in the name of the kind of hermetically-sealed war-time inclusiveness that only exists … well, it only exist in the motion pictures, as they say. This is the American road to freedom, with no pothole large or oppressive enough for Capra not to blanket over in warmth and saccharine sweetness (of course, a blanket isn’t going to stop you from falling into the American nightmare of racism if you get a little too close to reality for Capra’s comfort). One wonders what hell the devil John Huston would have wrought for one of his wartime propaganda films…  Mining conflicted stereotypes (alternately positive and negative and typically all of the above) of African-American culture wherein performance is nothing less than a fact of life and a principle of pure being, Stormy Weather reflects both WWII Hollywood’s sudden-onset awareness of black audiences and its indomitable drive to comb every inch of the American identity for souls to claim at the box office. Of course, this “sudden-onset awareness” was hardly circumstantial: with a significant portion of the movie-going audience abroad and embroiled in conflict (not that there wasn’t conflict on the homefront…) Hollywood suddenly discovered a reason to spread out its extremities in search of someone new to market to.

Mining conflicted stereotypes (alternately positive and negative and typically all of the above) of African-American culture wherein performance is nothing less than a fact of life and a principle of pure being, Stormy Weather reflects both WWII Hollywood’s sudden-onset awareness of black audiences and its indomitable drive to comb every inch of the American identity for souls to claim at the box office. Of course, this “sudden-onset awareness” was hardly circumstantial: with a significant portion of the movie-going audience abroad and embroiled in conflict (not that there wasn’t conflict on the homefront…) Hollywood suddenly discovered a reason to spread out its extremities in search of someone new to market to.