Referring to Guy Ritchie’s rather trivial take on the Matter of Britain, here are the three most interesting filmed versions of the tale.

Referring to Guy Ritchie’s rather trivial take on the Matter of Britain, here are the three most interesting filmed versions of the tale.

A million and one of us can hone in on a panoply of specific moments, turning critique of Monty Python and the Holy Grail into appreciation of Monty Python and the Holy Grail as well, not incidentally, an exercise in masturbatory self-congratulation. After all, the titular creators were sketch-artists and not narrative dramatists, so it goes without saying that Monty Python and the Holy Grail is a loosely-strung together hodgepodge of semi-connected and often contradictory, incommensurable pieces. But it’s the broad swath that impresses most, the keen eye for the scatter-brained nature of myths like Arthur that always seem to be trangentially reinterpreting themselves but not moving forward, struggling to plaster up the plot-holes in an essentially fuzzy and incomplete tale striving for the hazy appearance of sense. (The same, incidentally, is true of religion, which would be the Python’s next target). As a critique of the nature of sanding down the oddities and curiosities of a badly taped-together myth in order to approximate a precise narrative, Holy Grail actually makes a nice double-feature with the previous year’s Lancelot du Lac, the only other cinematic adaptation of the tale openly attuned to the fact that myths and legends only pretend to flow easily to hide the aporias and accidents that construct their very fabrics. Continue reading

Referring to Guy Ritchie’s rather trivial take on the Matter of Britain, here are the three most interesting filmed versions of the tale.

Referring to Guy Ritchie’s rather trivial take on the Matter of Britain, here are the three most interesting filmed versions of the tale. Dreamlike – and as lush as Mario Bava’s visual resplendence ever got – Lisa and the Devil is the half-crazed tipping point between the director’s earlier, Hitchcock-indebted slashers and the artistically emancipated deranged pop-art flourishes of his ward Dario Argento. Released in 1973 – and heavily recut two years later for American audiences to cash in on the Exorcist craze – Lisa is evidence not to paint Bava with the wide brush of obligatory pastiche, as though he was always performing his own idea of what a Bava film was supposed to be. Never stagnant, his films all reveal their personal eccentricities and oddities, the markers of a restless consciousness at work. A tragically comic fun-house reflection of existential panic, Lisa and the Devil recollects Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad to bridge the high and low art divide as Lisa (Elke Sommers) finds herself lost not only amidst Spanish corridors but time and space themselves.

Dreamlike – and as lush as Mario Bava’s visual resplendence ever got – Lisa and the Devil is the half-crazed tipping point between the director’s earlier, Hitchcock-indebted slashers and the artistically emancipated deranged pop-art flourishes of his ward Dario Argento. Released in 1973 – and heavily recut two years later for American audiences to cash in on the Exorcist craze – Lisa is evidence not to paint Bava with the wide brush of obligatory pastiche, as though he was always performing his own idea of what a Bava film was supposed to be. Never stagnant, his films all reveal their personal eccentricities and oddities, the markers of a restless consciousness at work. A tragically comic fun-house reflection of existential panic, Lisa and the Devil recollects Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad to bridge the high and low art divide as Lisa (Elke Sommers) finds herself lost not only amidst Spanish corridors but time and space themselves.  The title of this quintessentially ‘60s-product-of-hot-headed-Italy suggests a sex kitten romp, but the name is a much more literal in this deliciously macabre take on the spirit of Daphne de Maurier. As is seemingly the first commandment of all Giallos – to be obeyed with holy penitence – the narrative is paradoxically simple yet horrifyingly obtuse, but it boils down to the ghostly menace of young Melissa Graps terrorizing a European village around the turn of the 20th century, a village newly visited by a doctor (Giacomo Rossi Stuart) there to autopsy one of the bodies. Kill Baby, Kill also further develops Mario Bava’s formal fixation with the architectural impossibility of the mind. With one foot in the psycho-sexual and the other in the undulating tension between the supernatural and modern medicine, Kill Baby, Kill frolics with many of the thematic devils twisting the throat of mid-century life.

The title of this quintessentially ‘60s-product-of-hot-headed-Italy suggests a sex kitten romp, but the name is a much more literal in this deliciously macabre take on the spirit of Daphne de Maurier. As is seemingly the first commandment of all Giallos – to be obeyed with holy penitence – the narrative is paradoxically simple yet horrifyingly obtuse, but it boils down to the ghostly menace of young Melissa Graps terrorizing a European village around the turn of the 20th century, a village newly visited by a doctor (Giacomo Rossi Stuart) there to autopsy one of the bodies. Kill Baby, Kill also further develops Mario Bava’s formal fixation with the architectural impossibility of the mind. With one foot in the psycho-sexual and the other in the undulating tension between the supernatural and modern medicine, Kill Baby, Kill frolics with many of the thematic devils twisting the throat of mid-century life.  After a long way away, I’ll start posting pretty furiously for a while again. First up is a trio of Mario Bava films to celebrate the return of Midnight Screenings!

After a long way away, I’ll start posting pretty furiously for a while again. First up is a trio of Mario Bava films to celebrate the return of Midnight Screenings! Sometimes bemoaned for relegating himself to that most Japanese of genres – the samurai flick – and retreating into flavors of Americanization, director Akira Kurosawa performs something of an inside-out operation with High and Low. A fiendish film noir with fangs drawn at a vein spurting society’s maladies, High and Low casts the suspense picture out of its Americana corral by inducing a specifically Japanese flavor. Right from the get-go, Kurosawa’s film is hot on the trail of a molten morality play, teasing suggestions of violence that greasily spread like venom through the bones of Japanese society. Rather than mining his nation’s mythopoetic samurai memory and massaging it into an international sizzler primed for American audiences, this hyper-modern company-man thriller cuts a filmic diamond out of the suffocating coal of Japanese classism, squalor, and privilege. With its humid pangs of ethical disarray and pungent propositions of emotional upheaval, High and Low channels an ever-mutable dialogue between social codes and personal feelings, exploring an uncharted territory where each is informed by and negotiates the other.

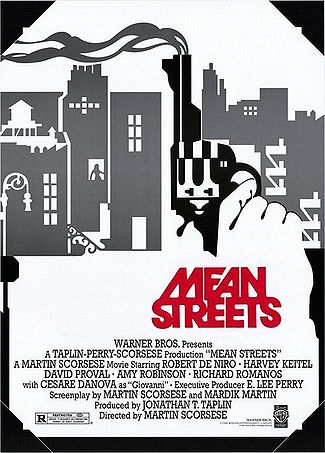

Sometimes bemoaned for relegating himself to that most Japanese of genres – the samurai flick – and retreating into flavors of Americanization, director Akira Kurosawa performs something of an inside-out operation with High and Low. A fiendish film noir with fangs drawn at a vein spurting society’s maladies, High and Low casts the suspense picture out of its Americana corral by inducing a specifically Japanese flavor. Right from the get-go, Kurosawa’s film is hot on the trail of a molten morality play, teasing suggestions of violence that greasily spread like venom through the bones of Japanese society. Rather than mining his nation’s mythopoetic samurai memory and massaging it into an international sizzler primed for American audiences, this hyper-modern company-man thriller cuts a filmic diamond out of the suffocating coal of Japanese classism, squalor, and privilege. With its humid pangs of ethical disarray and pungent propositions of emotional upheaval, High and Low channels an ever-mutable dialogue between social codes and personal feelings, exploring an uncharted territory where each is informed by and negotiates the other.  A dive-bar livid with unvarnished restlessness, Martin Scorsese’s first “big picture” breakthrough is no mere chopping block for his later, more famous regurgitations of his pet themes: Catholic guilt, boys being boys, male angst, un-placeable inner-city maladies. Instead, Mean Streets is all the more probing for its out-of-focus, improvisational gusto. It lacks the “perfect” formalist backbone of The Brow’s later Taxi Driver, Scorsese’s perverted poison-pen letter to classical Hollywood noirs as well as a codified conduit for writer Paul Schrader’s meditations of transcendence and Robert Bresson. But while more noncommittal and less precise on the surface, Mean Streets’ libertine energy and scruffy, scrappy, unfocused workaday energy actually bests its more confident younger sibling for sheer restlessness.

A dive-bar livid with unvarnished restlessness, Martin Scorsese’s first “big picture” breakthrough is no mere chopping block for his later, more famous regurgitations of his pet themes: Catholic guilt, boys being boys, male angst, un-placeable inner-city maladies. Instead, Mean Streets is all the more probing for its out-of-focus, improvisational gusto. It lacks the “perfect” formalist backbone of The Brow’s later Taxi Driver, Scorsese’s perverted poison-pen letter to classical Hollywood noirs as well as a codified conduit for writer Paul Schrader’s meditations of transcendence and Robert Bresson. But while more noncommittal and less precise on the surface, Mean Streets’ libertine energy and scruffy, scrappy, unfocused workaday energy actually bests its more confident younger sibling for sheer restlessness. Ninety-two years on, it goes without saying that Battleship Potemkin is a sketch more than an aria, but Eisenstein stencils better than just about anyone. Disposing with the character-first politics of American cinema then expediently working overtime with enough charisma to turn film into the de facto bourgeois art form, Potemkin is politically flimsy. But that’s acceptable: it’s a polemic, a red-hot screed, the charred apex of a garbled wail of revolutionary fervor, and if it isn’t quite the feeding frenzy for inventive technique that Strike or some of Eisenstein’s future films were, it’s exciting enough to fulfill Pauline Kael’s declaration (on another film) of the proverbial “movie in heat”. Agitprop it is, which isn’t a problem. The issue, and it is exclusively relative (that of a lesser masterpiece vs. Strike, a greater masterpiece) is that this particular agitator isn’t as agitated as Eisenstein’s greatest films.

Ninety-two years on, it goes without saying that Battleship Potemkin is a sketch more than an aria, but Eisenstein stencils better than just about anyone. Disposing with the character-first politics of American cinema then expediently working overtime with enough charisma to turn film into the de facto bourgeois art form, Potemkin is politically flimsy. But that’s acceptable: it’s a polemic, a red-hot screed, the charred apex of a garbled wail of revolutionary fervor, and if it isn’t quite the feeding frenzy for inventive technique that Strike or some of Eisenstein’s future films were, it’s exciting enough to fulfill Pauline Kael’s declaration (on another film) of the proverbial “movie in heat”. Agitprop it is, which isn’t a problem. The issue, and it is exclusively relative (that of a lesser masterpiece vs. Strike, a greater masterpiece) is that this particular agitator isn’t as agitated as Eisenstein’s greatest films.  At once a howling abyss and a succulent morsel of semi-absurdist humanistic comedy, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North is a film of wonderfully unresolved, immanent contradictions and multivalent constellations of primordial beauty. The most obvious dormant tension that requires surfacing is that it isn’t a documentary, at least insofar as the conventional scripture would bequeath it. No, this slice-of-life tale of “Nanook” (actually Allakariallak), an Inuit in the arctic regions of Canada, as filmed by filmmaker-explorer Robert Flaherty, was largely an ahistorical concoction fabricated to feign allegiance to the Western ideology of the Inuit as a backward Other whose life was governed by genial amusement and befuddlement at any and all Western artifacts. Many of these technologies objects were well-known to Allakariallak, a genuine Inuit who was “in” on the production of the film, as Inuit culture by 1922 had advanced well beyond the spear-wielding icon curated by Flaherty for white America’s racial memory.

At once a howling abyss and a succulent morsel of semi-absurdist humanistic comedy, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North is a film of wonderfully unresolved, immanent contradictions and multivalent constellations of primordial beauty. The most obvious dormant tension that requires surfacing is that it isn’t a documentary, at least insofar as the conventional scripture would bequeath it. No, this slice-of-life tale of “Nanook” (actually Allakariallak), an Inuit in the arctic regions of Canada, as filmed by filmmaker-explorer Robert Flaherty, was largely an ahistorical concoction fabricated to feign allegiance to the Western ideology of the Inuit as a backward Other whose life was governed by genial amusement and befuddlement at any and all Western artifacts. Many of these technologies objects were well-known to Allakariallak, a genuine Inuit who was “in” on the production of the film, as Inuit culture by 1922 had advanced well beyond the spear-wielding icon curated by Flaherty for white America’s racial memory.  I meant to get to this a bit ago, obviously, but this review is in memorium to the dearly departed demon of cinema Seijun Suzuki.

I meant to get to this a bit ago, obviously, but this review is in memorium to the dearly departed demon of cinema Seijun Suzuki.