As opposed to an abject failure of imagination, design, or cinema more broadly, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace suffers a more equivocal, ambiguous form of misfortune, the kind of flaw that is also signally exciting and valuable in its own right: it suffers deeply from 16 years of franchise-creator George Lucas stewing on his ideas. With The Phantom Menace, the lower rungs of his imagination inflated to the point of boiling over with a desperate need to prove his mettle as an author by complicating and nuancing the concept for Star Wars without actually having a grasp on, or paying attention to, the actual execution, the very cinema, of his ideas. Everyone loves to hate on the thing, slathering it in such a smothering aura of empty incompetence that the criticism seems not only unfair but essentially arbitrary. In point of fact, the film is often anything but empty, and its surfeit of under-baked ideas – exciting to a point – are also its comeuppance. The totalizing way everyone demonizes the thing like it’s a leper unable to scrutinized up close asphyxiates not only the filigrees of glee inhabiting the film from time to time but its more legitimate offenses as well. Continue reading

As opposed to an abject failure of imagination, design, or cinema more broadly, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace suffers a more equivocal, ambiguous form of misfortune, the kind of flaw that is also signally exciting and valuable in its own right: it suffers deeply from 16 years of franchise-creator George Lucas stewing on his ideas. With The Phantom Menace, the lower rungs of his imagination inflated to the point of boiling over with a desperate need to prove his mettle as an author by complicating and nuancing the concept for Star Wars without actually having a grasp on, or paying attention to, the actual execution, the very cinema, of his ideas. Everyone loves to hate on the thing, slathering it in such a smothering aura of empty incompetence that the criticism seems not only unfair but essentially arbitrary. In point of fact, the film is often anything but empty, and its surfeit of under-baked ideas – exciting to a point – are also its comeuppance. The totalizing way everyone demonizes the thing like it’s a leper unable to scrutinized up close asphyxiates not only the filigrees of glee inhabiting the film from time to time but its more legitimate offenses as well. Continue reading

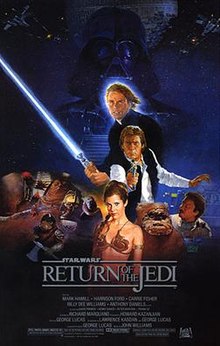

Progenitors: Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi

After the down-tuned-pulp pop space-opera of the original Star Wars and the astounding, apocalyptic depression of The Empire Strikes Back, what do George Lucas and his goons give us for round three? Neither fish nor fowl, but an extraordinarily and sometimes beguilingly stitched-together accident, a film loaded with and defined by peculiar tonal spasms and the kind of narratively-haphazard mess you just can’t get without a devoutly, almost feverishly passionate but mildly inept creative figure at the helm. Yes, Return of the Jedi is a travesty of writing on par with any of the prequels. But the real question is how it mobilizes its mess, whether it treats cinematic dysfunction as a liberating deliverance from acquiescence to middlebrow, mainstream cinematic perfection or as simple incompetence. Far from catastrophic but still strangely mishandled in ways both exciting and hindering, Return of the Jedi wears it fleet of script revisions and swamp of behind-the-scenes misgivings like a ball and chain. Every image, good and bad alike, are portals into the often dysfunctional production of this film as well as the obvious casualties of market success, both factors that are only barely hidden on camera. Continue reading

After the down-tuned-pulp pop space-opera of the original Star Wars and the astounding, apocalyptic depression of The Empire Strikes Back, what do George Lucas and his goons give us for round three? Neither fish nor fowl, but an extraordinarily and sometimes beguilingly stitched-together accident, a film loaded with and defined by peculiar tonal spasms and the kind of narratively-haphazard mess you just can’t get without a devoutly, almost feverishly passionate but mildly inept creative figure at the helm. Yes, Return of the Jedi is a travesty of writing on par with any of the prequels. But the real question is how it mobilizes its mess, whether it treats cinematic dysfunction as a liberating deliverance from acquiescence to middlebrow, mainstream cinematic perfection or as simple incompetence. Far from catastrophic but still strangely mishandled in ways both exciting and hindering, Return of the Jedi wears it fleet of script revisions and swamp of behind-the-scenes misgivings like a ball and chain. Every image, good and bad alike, are portals into the often dysfunctional production of this film as well as the obvious casualties of market success, both factors that are only barely hidden on camera. Continue reading

Progenitors: Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

With the release of The Last Jedi, I’ll be reviewing every Star Wars film not currently covered on this site, which means all the pre-Disney films excepting the indomitable Empire.

Star Wars fan-boys fall head over heels for George Lucas’ world-building, but the standout quality of Lucas’ first Star Wars film is it vision of a world already built, destroyed, and stratified. Narratively and commercially an infamous break from the serious dramas of the New Hollywood during the early ‘70s, the visual style of Star Wars is nonetheless heavily schooled in the dog-tired, emptied-out malnourishment of ‘70s cynicism. The town of Mos Eisley in particular, druggy, hallucinogenic Cantina aside, could slide neatly into any washed-out Southwestern American state circa 1977. Visually, Star Wars bears all the bruised beauty and shambolic, hang-dog lethargy of a revisionist Western.

Narratively, of course, it’s another story. It’s for the best that the plot can be summed up so eloquently, because the film certainly doesn’t always do so. Lucas’ underrated knack for visual suggestion is not even remotely matched by his lead-footed screenwriting most obviously reflected in his infamously explanatory, banal dialogue that reverberates like human reason gone truly haywire. But we’re not there yet. For the moment, let’s just say that the dramatic outline – Star Wars works best as a sketchbook galvanized as a bracing series of beautiful visual stanzas – is essentially great, or at least potentially great when it is fertilized by Lucas’ imagery. Continue reading

Review: Blade Runner 2049

I consider myself someone who takes cinema very seriously. But “serious” in this sense is a question of attitude and sensibility rather than tone. I take seriously the ability of cinema to plumb its inner-depths and expand its outer-registers, to twist and turn preconceptions about existence, to interrogate its own mortal coil and material medium as well as to dialogue with social context, to refresh itself, to treat every moment as a contingency rather than a certainty. But above all, I take seriously cinema’s ability to play: with itself, with the world, and with its conception of the world. Play does not imply glib triviality or even humor but the giddy effervescence steaming off of even the most solemn and sober film as it treats its medium as an experiment in any tone whatsoever. Serious play incorporates thematic, intellectual, emotional, philosophical, visual, spatial, temporal, and aural play in all its registers, the excitement of a film that is gloriously unsettled in its always-roving, never-finished mental exploration of self. Seriousness, in this lexicon, does not entail giving a pass to so-called serious cinema, especially cinema which wraps itself up in its seriousness as a hermetic seal, as a shield from real self-interrogation, or as position of sacrosanct refuge. Continue reading

I consider myself someone who takes cinema very seriously. But “serious” in this sense is a question of attitude and sensibility rather than tone. I take seriously the ability of cinema to plumb its inner-depths and expand its outer-registers, to twist and turn preconceptions about existence, to interrogate its own mortal coil and material medium as well as to dialogue with social context, to refresh itself, to treat every moment as a contingency rather than a certainty. But above all, I take seriously cinema’s ability to play: with itself, with the world, and with its conception of the world. Play does not imply glib triviality or even humor but the giddy effervescence steaming off of even the most solemn and sober film as it treats its medium as an experiment in any tone whatsoever. Serious play incorporates thematic, intellectual, emotional, philosophical, visual, spatial, temporal, and aural play in all its registers, the excitement of a film that is gloriously unsettled in its always-roving, never-finished mental exploration of self. Seriousness, in this lexicon, does not entail giving a pass to so-called serious cinema, especially cinema which wraps itself up in its seriousness as a hermetic seal, as a shield from real self-interrogation, or as position of sacrosanct refuge. Continue reading

Film Favorites: Blood Simple

Until 2007 when they unchained No Country for Old Men on unwitting audiences, Blood Simple was the black sheep of the Coen Brothers family. Their second feature Raising Arizona is, on the surface, its diametric opposite, a harried, maniacal fracas of disheveled lunacy and Southwestern loneliness. That latter film has, more or less, paved the way for many of the Coen Brothers’ more famous features, inaugurating their reputation as the pied pipers of modern artful screwball. But Arizona shares two central components with its predecessor despite Blood Simple’s reputation as the wild card in their canon. Tones aside, both films are mordant, fiendishly cunning grasps of dour, melancholic tragedy, both comedies-of-loneliness. And both are acid-washed images of people in need of an escape hatch. The sheer surfeit of mood aside, Blood Simple frequently feels like a premonition of the Coen Brothers’ entire career. Considering Blood Simple reveals the crestfallen image of a destitute US and stunted, criminally miscommunicating people that skulks, almost subterraneanly, within the notionally-chipper heart of many of their later films. Continue reading

Until 2007 when they unchained No Country for Old Men on unwitting audiences, Blood Simple was the black sheep of the Coen Brothers family. Their second feature Raising Arizona is, on the surface, its diametric opposite, a harried, maniacal fracas of disheveled lunacy and Southwestern loneliness. That latter film has, more or less, paved the way for many of the Coen Brothers’ more famous features, inaugurating their reputation as the pied pipers of modern artful screwball. But Arizona shares two central components with its predecessor despite Blood Simple’s reputation as the wild card in their canon. Tones aside, both films are mordant, fiendishly cunning grasps of dour, melancholic tragedy, both comedies-of-loneliness. And both are acid-washed images of people in need of an escape hatch. The sheer surfeit of mood aside, Blood Simple frequently feels like a premonition of the Coen Brothers’ entire career. Considering Blood Simple reveals the crestfallen image of a destitute US and stunted, criminally miscommunicating people that skulks, almost subterraneanly, within the notionally-chipper heart of many of their later films. Continue reading

Christmas Favorites: A Charlie Brown Christmas

I’ve been away for so long … Here’s a holiday classic to re-inaugurate the site.

I’ve been away for so long … Here’s a holiday classic to re-inaugurate the site.

Fifty two years later, Bill Melendez’s first television special adaptation of Charles Schultz’ Peanuts comic strip remains not only the most unshakably apprehensive, despondent animation in the entire series but the most unmediated, direct transmission from Schultz’ famously depressing comics so palpably informed by middle-age anti-nostalgia. Critics are extremely fond of slippery-slopes about “adult” Christmas cinema. They turn every minute flicker of violence or filigree of naughty language into a claim that their favored Christmas adaptation is the one that truly harbors darker thoughts about the holiday spirit lurking around the corners of its thought. They defend everything form Die Hard to Gremlins to Lethal Weapon – seemingly every circumstantially-Christmas-set film released in the ‘80s – as emblematic of a more perverse Christmas sensibility of merry travesty. This curdled, nasty sentiment that uses Christmas as a victim to beat with its own candy canes has since blossomed further into a typically cringe-inducing glut known as Christmas horror cinema and more overtly bad-tempered lumps of coal like Bad Santa. Continue reading

Film Favorites: Y Tu Mama Tambien

Y Tu Mama Tambien is inauspicious, but like many great films, it reaches for and touches the world and humanity in everyday actions and seemingly small gestures. Here, for instance, we have teen sexuality, laid out with all its romanticism and reality, filled with the kinds of empty-but-meaningful gestures that define humanity’s desires and their foibles. Director Alfonso Cuaron is a highly personal director, but he’s always most interested in defining his characters in relation to the world they inhabit. His two protagonists here are immature and petty yet deeply human, reflections of a society that won’t admit it has given birth to them and which they, initially, want no part in. He gives us a profoundly human story, built on the eternal humanness of sex as a marker of adulthood and childishness, and given life by Cuaron’s wonderfully and contrapuntally painterly version of sloppy, slovenly reality. Continue reading

Y Tu Mama Tambien is inauspicious, but like many great films, it reaches for and touches the world and humanity in everyday actions and seemingly small gestures. Here, for instance, we have teen sexuality, laid out with all its romanticism and reality, filled with the kinds of empty-but-meaningful gestures that define humanity’s desires and their foibles. Director Alfonso Cuaron is a highly personal director, but he’s always most interested in defining his characters in relation to the world they inhabit. His two protagonists here are immature and petty yet deeply human, reflections of a society that won’t admit it has given birth to them and which they, initially, want no part in. He gives us a profoundly human story, built on the eternal humanness of sex as a marker of adulthood and childishness, and given life by Cuaron’s wonderfully and contrapuntally painterly version of sloppy, slovenly reality. Continue reading

Halloween Review: It Comes at Night

Vis-a-vis the more trimly-titled but flabbily-filmed It: now this is more like it. The second feature from Trey Edward Shults, It Comes at Night trades out the high-gloss carnival-esque of Muschietti’s film for the kind of slowly-curdling angst and stomach-rotting apprehension that not only startles the hairs on the end of your arms but rattles and disquiets the bones. It Comes at Night is not peak horror compared to some of the recent finds in the genre since 2010 – It Follows, to name another title to wield the willful ambiguity of one particular pronoun – and this new film manages the unfortunate (commendable?) feat of being both too literal and too equivocal for its own good. But compared to the lazy imprecision of It, Shults’ film is a real wilderness of human fear. Continue reading

Vis-a-vis the more trimly-titled but flabbily-filmed It: now this is more like it. The second feature from Trey Edward Shults, It Comes at Night trades out the high-gloss carnival-esque of Muschietti’s film for the kind of slowly-curdling angst and stomach-rotting apprehension that not only startles the hairs on the end of your arms but rattles and disquiets the bones. It Comes at Night is not peak horror compared to some of the recent finds in the genre since 2010 – It Follows, to name another title to wield the willful ambiguity of one particular pronoun – and this new film manages the unfortunate (commendable?) feat of being both too literal and too equivocal for its own good. But compared to the lazy imprecision of It, Shults’ film is a real wilderness of human fear. Continue reading

Halloween Review: It (2017)

In Andy Muschietti’s sturdy but superficial, journeyman remake of It, Bill Skarsgard’s portrayal of the title role is a too-easy thesis of the film’s successes and flaws. On one hand, when Tim Curry stepped into the fangs and red hair in 1990, he was a memorably polychromatic experience: sad, otherworldly, ethereal, campy, and bizarre. Skarsgaard only hits – or is only allowed to aim for – unadulterated fright. On the other hand, his more calculated performance less prone to tangents and instabilities capably invokes the gloomy glint of terror that animates this new film, one-note in its construction but perfectly capable of hitting the note. Curry was the standout in that earlier, now-epochal television film – it jump-started an insufferable trend of Stephen King TV mini-series that continues to this day – but the unwieldly, tone-deaf drudgery of that production was an unstable mess of arbitrarily-laid-out scenes lacking any semblance of cohesion or logic. (Nor was it, incidentally, meaningful with its mess). Intersecting feelings and emotions could be both fascinatingly tiring and pointlessly, scene-paddingly draining. Continue reading

In Andy Muschietti’s sturdy but superficial, journeyman remake of It, Bill Skarsgard’s portrayal of the title role is a too-easy thesis of the film’s successes and flaws. On one hand, when Tim Curry stepped into the fangs and red hair in 1990, he was a memorably polychromatic experience: sad, otherworldly, ethereal, campy, and bizarre. Skarsgaard only hits – or is only allowed to aim for – unadulterated fright. On the other hand, his more calculated performance less prone to tangents and instabilities capably invokes the gloomy glint of terror that animates this new film, one-note in its construction but perfectly capable of hitting the note. Curry was the standout in that earlier, now-epochal television film – it jump-started an insufferable trend of Stephen King TV mini-series that continues to this day – but the unwieldly, tone-deaf drudgery of that production was an unstable mess of arbitrarily-laid-out scenes lacking any semblance of cohesion or logic. (Nor was it, incidentally, meaningful with its mess). Intersecting feelings and emotions could be both fascinatingly tiring and pointlessly, scene-paddingly draining. Continue reading

Halloween Review: Raw

The feverish French-language coming-of-age-horror-comedy Raw has many selves, not all of them exhibited at the same time. But the somewhat frequent and always volatile transformations of its core being are at worst spirited, and more often than not, they amount to a kind of thematic-jukebox. The film’s somewhat vague attitude to theme allows writer-director Julia Ducornau to (over?)populate a thread of a narrative – a young freshman named Justine (Garance Marillier) at a vet school – with tensions of various calibers that rhyme with the peculiarities and curiosities of adolescence without necessarily committing to one central argument. When Justine develops increasingly erratic behavior and eventually a taste for human flesh after a hazing ritual involving eating a rabbit kidney, Ducornau’s thematically-promiscuous film reacts the only way it knows how: deploying the nonliteral beauty of horror cinema. Rendering sympathetic abstractions of issues from institutional neglect to gender awareness, Ducornau metaphorically challenges easily normalized realities and then galvanizes them with the grossly peculiar, unknown curveball of horror cinema. Continue reading

The feverish French-language coming-of-age-horror-comedy Raw has many selves, not all of them exhibited at the same time. But the somewhat frequent and always volatile transformations of its core being are at worst spirited, and more often than not, they amount to a kind of thematic-jukebox. The film’s somewhat vague attitude to theme allows writer-director Julia Ducornau to (over?)populate a thread of a narrative – a young freshman named Justine (Garance Marillier) at a vet school – with tensions of various calibers that rhyme with the peculiarities and curiosities of adolescence without necessarily committing to one central argument. When Justine develops increasingly erratic behavior and eventually a taste for human flesh after a hazing ritual involving eating a rabbit kidney, Ducornau’s thematically-promiscuous film reacts the only way it knows how: deploying the nonliteral beauty of horror cinema. Rendering sympathetic abstractions of issues from institutional neglect to gender awareness, Ducornau metaphorically challenges easily normalized realities and then galvanizes them with the grossly peculiar, unknown curveball of horror cinema. Continue reading