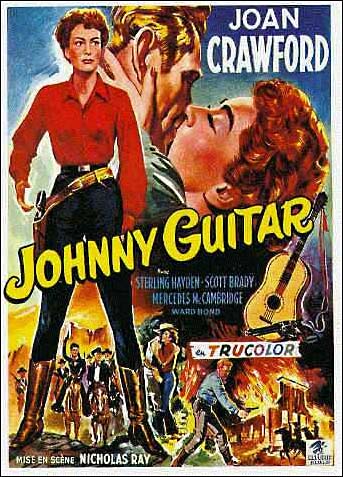

Is there any way to announce a consideration of Johnny Guitar other than the now famous Jean-Luc Godard quote about Nicholas Ray being “cinema”? Famously, the director expressed that Ray was among the first, if not the first, American auteurs to do with cinema as only cinema could, taking up the poetry of dialogue and the untarnished, painterly quality of art and the distant timelessness of theater and encircling them with the vulture of film, engorging itself on the carcasses of other mediums and ensuring they lived on, in altered, transmuted form, inside cinema.

Is there any way to announce a consideration of Johnny Guitar other than the now famous Jean-Luc Godard quote about Nicholas Ray being “cinema”? Famously, the director expressed that Ray was among the first, if not the first, American auteurs to do with cinema as only cinema could, taking up the poetry of dialogue and the untarnished, painterly quality of art and the distant timelessness of theater and encircling them with the vulture of film, engorging itself on the carcasses of other mediums and ensuring they lived on, in altered, transmuted form, inside cinema.

Godard’s quote is a touch too heated (I’ll take to my grave the thought that Nicholas Ray is among the most underrated auteurs Hollywood ever produced, but that he was the first true advocate of “cinema” is a much more difficult proposition). Certainly, however, Ray’s films always felt more alive with pulsation, even in their embalmed detachment, than those of many other auteurs. And Godard naturally felt the love due to Ray’s unparalleled work in genre as a means of classifying social incoherence and expressing differing views of humanity’s own artifice. If he wasn’t the first true cinematic visionary, he was up there with the greats of his or any other time. Continue reading

Everybody’s been talking about it lately, but the Academy is on a nervous show-biz kick recently, with The Artist, Argo, and most recently Birdman winning Best Picture awards in a new glut of the much vaunted “films about films” genre (even if, in Birdman, as it is in many other works, film is only ever sub-textual). Shockingly, you really have to go back sixty five years for another film about the art of stagecraft to win a Best Picture award, and since nearly every review of Birdman has compared it to a certain self-hating implosion from Joseph L. Mankiewicz, I figured Birdman’s award last Sunday is as deserving a reason as any to actually edit and post the review of All About Eve I wrote sometime around like last August (I was busy in the ensuing half year, it turns out). Enjoy!

Everybody’s been talking about it lately, but the Academy is on a nervous show-biz kick recently, with The Artist, Argo, and most recently Birdman winning Best Picture awards in a new glut of the much vaunted “films about films” genre (even if, in Birdman, as it is in many other works, film is only ever sub-textual). Shockingly, you really have to go back sixty five years for another film about the art of stagecraft to win a Best Picture award, and since nearly every review of Birdman has compared it to a certain self-hating implosion from Joseph L. Mankiewicz, I figured Birdman’s award last Sunday is as deserving a reason as any to actually edit and post the review of All About Eve I wrote sometime around like last August (I was busy in the ensuing half year, it turns out). Enjoy! A menacing, spellbinding little monstrosity from Pre-Code era Hollywood, Island of Lost Souls is perhaps the only early-sound American horror film to challenge the supremacy of Universal pictures for its unprecedented monopoly on the genre through the ’30s (the ’40s were much less kind to a company that increasingly became a corporate sequel-shill, but Val Lewton was there to save the genre from total oblivion). Kicking off an under-respected tradition of great, forward-thinking, alert, provocative HG Wells adaptations through the ’30s (even Orson Welles got involved), Island of Lost Souls is about as fine a beginning to a legacy as you could hope for. Dealing with the monomaniacal and the perverse with equal artistry and frankness, Erle Kenton’s film appears urgently modern, free of restrictions, and alive with discovery.

A menacing, spellbinding little monstrosity from Pre-Code era Hollywood, Island of Lost Souls is perhaps the only early-sound American horror film to challenge the supremacy of Universal pictures for its unprecedented monopoly on the genre through the ’30s (the ’40s were much less kind to a company that increasingly became a corporate sequel-shill, but Val Lewton was there to save the genre from total oblivion). Kicking off an under-respected tradition of great, forward-thinking, alert, provocative HG Wells adaptations through the ’30s (even Orson Welles got involved), Island of Lost Souls is about as fine a beginning to a legacy as you could hope for. Dealing with the monomaniacal and the perverse with equal artistry and frankness, Erle Kenton’s film appears urgently modern, free of restrictions, and alive with discovery. In honor of another Wachowski bullet ready to be thrown away and left out in the cold by an undiscerning society, Jupiter Ascending, here is a review of their previous film, a work that draws out their strengths and weaknesses for creating passionate, alive, messy, confused, singular cinema like few others.

In honor of another Wachowski bullet ready to be thrown away and left out in the cold by an undiscerning society, Jupiter Ascending, here is a review of their previous film, a work that draws out their strengths and weaknesses for creating passionate, alive, messy, confused, singular cinema like few others.  Edited June 2016

Edited June 2016 First aired in 1999, the “SpongeBob” animated television show is defined primarily by an aesthetic of chill, off-the-cuff, non-confrontational madness. It is a show left uncontrolled with its own id in a room, forced to confront its own nonsense and live with it and have the most glorious time of its existence simply being itself. It is a wonderful slice of animation as character definition, radical in subtle ways and existential and playful without ever seeming over-worked or tired. Above all, it never really seems to try. It simply exists in its own state, not so much working to function a certain way as laying itself down and exploring whatever comes out of its mind at that moment. It seems gloriously uncontainable, but never too hungry to lash out or rush around for the sake of energy in every direction it can. It’s a show of quiet confusion, aloof froth, and lazy charm. It is something that does not seem to have been produced or created, but found and observed. It is free of exposition, free of explanation. It is pure, un-worked, and unworkable. It seems effortless.

First aired in 1999, the “SpongeBob” animated television show is defined primarily by an aesthetic of chill, off-the-cuff, non-confrontational madness. It is a show left uncontrolled with its own id in a room, forced to confront its own nonsense and live with it and have the most glorious time of its existence simply being itself. It is a wonderful slice of animation as character definition, radical in subtle ways and existential and playful without ever seeming over-worked or tired. Above all, it never really seems to try. It simply exists in its own state, not so much working to function a certain way as laying itself down and exploring whatever comes out of its mind at that moment. It seems gloriously uncontainable, but never too hungry to lash out or rush around for the sake of energy in every direction it can. It’s a show of quiet confusion, aloof froth, and lazy charm. It is something that does not seem to have been produced or created, but found and observed. It is free of exposition, free of explanation. It is pure, un-worked, and unworkable. It seems effortless.  Ahem. “Faced with the overwhelming stubborn mule that is the American girth of racism and backward stagnancy, Martin Luther King (David Oyelowo) uneasily fuses together a coalition of the willing (and unwilling) toward showing America the full extent of its wrongs and doing whatever he can to pursue a greater right”. With a story like that, one would be forgiven for assuming all the hype around Selma boils down to a work of reigned-in Oscarbait, safe and streamlined and ready and willing to fall in love with its own saccharine self. It would seem this crowd-pleasing lull is the de facto state of the corporate biopic, flying high on easy, over-written drama and hagiography, indifferently filmed, edited, composed, and photographed, and resting almost entirely on the laurels of the main actor/ actress in the lead role.

Ahem. “Faced with the overwhelming stubborn mule that is the American girth of racism and backward stagnancy, Martin Luther King (David Oyelowo) uneasily fuses together a coalition of the willing (and unwilling) toward showing America the full extent of its wrongs and doing whatever he can to pursue a greater right”. With a story like that, one would be forgiven for assuming all the hype around Selma boils down to a work of reigned-in Oscarbait, safe and streamlined and ready and willing to fall in love with its own saccharine self. It would seem this crowd-pleasing lull is the de facto state of the corporate biopic, flying high on easy, over-written drama and hagiography, indifferently filmed, edited, composed, and photographed, and resting almost entirely on the laurels of the main actor/ actress in the lead role. Predestination is so close to being just another in a long line of too on-the-nose puzzle box movies. So much of what it does is ape the sort of sub-Christopher Nolan modern-era “betcha can’t guess where this is going to go?” holier-than-thou smug superiority that sacrifices visual nuance and crafty characterization for placing viewers in an icy cold puzzle box that was hired instead of a story. It’s so close to not working that its kind of a miracle it does work at all. It’s even more of a miracle that so much of why it works is in the acting, my much-chagrined “don’t care” department and perennial vote for “most overrated thing about the whole cloth of cinema”. Besides story, of course.

Predestination is so close to being just another in a long line of too on-the-nose puzzle box movies. So much of what it does is ape the sort of sub-Christopher Nolan modern-era “betcha can’t guess where this is going to go?” holier-than-thou smug superiority that sacrifices visual nuance and crafty characterization for placing viewers in an icy cold puzzle box that was hired instead of a story. It’s so close to not working that its kind of a miracle it does work at all. It’s even more of a miracle that so much of why it works is in the acting, my much-chagrined “don’t care” department and perennial vote for “most overrated thing about the whole cloth of cinema”. Besides story, of course. The Boy Next Door is a film alive with the sense of discovery that “yes, a film can be this bad in 2015”, and it is astoundingly welcome for this reason. Directed Rob Cohen, who still exists apparently, and starring Jennifer Lopez, who also sometimes remembers that she is an actual person, The Boy Next Door is a riot, plain and simple, and it seems to have absolutely no sense that it is. Just the idea alone works wonders: a high school English teacher (Jennifer Lopez) who has an affair with local resident supposed-nice-guy, takes-care-of-his-paraplegic-uncle, male-model, good-with-his-hands-if-you-know-what-I-mean Noah Sandborn (Ryan Guzman). All is well and good, until he turns out to be a particularly abusive male-privilege hound who obsesses over her and is willing to kill to get what he wants.

The Boy Next Door is a film alive with the sense of discovery that “yes, a film can be this bad in 2015”, and it is astoundingly welcome for this reason. Directed Rob Cohen, who still exists apparently, and starring Jennifer Lopez, who also sometimes remembers that she is an actual person, The Boy Next Door is a riot, plain and simple, and it seems to have absolutely no sense that it is. Just the idea alone works wonders: a high school English teacher (Jennifer Lopez) who has an affair with local resident supposed-nice-guy, takes-care-of-his-paraplegic-uncle, male-model, good-with-his-hands-if-you-know-what-I-mean Noah Sandborn (Ryan Guzman). All is well and good, until he turns out to be a particularly abusive male-privilege hound who obsesses over her and is willing to kill to get what he wants. A critic should be honest about their biases. Considering this, a preface: Beyond the Black Rainbow is conventionally described, at least insofar as a film this atypical can be conventionally described, as a modern recollection of the grainy, quizzical, hard science fiction storytelling so popular in 1970s US culture, doused with a thin membrane of stilted, personality-heavy American animation forever struggling to find out what it meant to aim for an audience of both children and adults. Considering this, it would have been almost impossible for me to dislike the film going on. As it turns out, I do not dislike it. Take from that what you will.

A critic should be honest about their biases. Considering this, a preface: Beyond the Black Rainbow is conventionally described, at least insofar as a film this atypical can be conventionally described, as a modern recollection of the grainy, quizzical, hard science fiction storytelling so popular in 1970s US culture, doused with a thin membrane of stilted, personality-heavy American animation forever struggling to find out what it meant to aim for an audience of both children and adults. Considering this, it would have been almost impossible for me to dislike the film going on. As it turns out, I do not dislike it. Take from that what you will.