Ever since the truly sublime Monty Python’s Flying Circus sketch “Salad Days”, Sam Peckinpah has been something of a punchline for critics who reduce him to the rampant Novocaine of violence opiating the masses. His only proper war film, Cross of Iron, is not a full-throated rejoinder to that criticism, but it certainly problematizes the animating cinematic thrill of, say, The Wild Bunch. It’s not an abandonment of violence, though, so much as a rough and rowdy revision, punchy in the typical Peckinpah milieu but more decrepit and alienated from its bloodletting.

Ever since the truly sublime Monty Python’s Flying Circus sketch “Salad Days”, Sam Peckinpah has been something of a punchline for critics who reduce him to the rampant Novocaine of violence opiating the masses. His only proper war film, Cross of Iron, is not a full-throated rejoinder to that criticism, but it certainly problematizes the animating cinematic thrill of, say, The Wild Bunch. It’s not an abandonment of violence, though, so much as a rough and rowdy revision, punchy in the typical Peckinpah milieu but more decrepit and alienated from its bloodletting.

The introduction is a little over-baked, but it works as a sort of amuse-bouche for Peckinpah’s exceedingly dry comic sensibility, with a documentary video-reel of Nazi imagery marinated in an overtly condescending, cheeky military march. Great stuff, and it reveals a truly mordant sense of humor underneath Peckinpah’s usually stone-faced cinematic exteriors. Peckinpah also inverts the famous opening credits of The Wild Bunch, where color soldiers unsympathetically flash into still-photo black-and-white as if to trap them in time and enervate them of life-blood. Here, the black and white footage flashes into static blood-red, as if the distanced and denatured imagery of the past is being provocatively reinstated as a bloody present. Continue reading

Ahh, the wonderful world of John Boorman, that perennial cinematic oscillator between the realm of exhausted greatness (Point Break, Deliverance) and spirited atrocity (Zardoz and Exorcist II). The man just eludes categorization, except that all of his films seem to share a pure and unabashed self-centeredness. Yet many of his best films paradoxically stamp themselves in the director’s personality not through baroque visual extravaganzas but through thriller minimalism. His greatest achievements are not screeds radiating shards of discontent or phantasmagorical whirlygusts of excitement. Deliverance and Point Break are white-knuckle, certainly, but they are also thoroughly dog-tired, whipped features, spent forces rather than self-propagating fires of combustion.

Ahh, the wonderful world of John Boorman, that perennial cinematic oscillator between the realm of exhausted greatness (Point Break, Deliverance) and spirited atrocity (Zardoz and Exorcist II). The man just eludes categorization, except that all of his films seem to share a pure and unabashed self-centeredness. Yet many of his best films paradoxically stamp themselves in the director’s personality not through baroque visual extravaganzas but through thriller minimalism. His greatest achievements are not screeds radiating shards of discontent or phantasmagorical whirlygusts of excitement. Deliverance and Point Break are white-knuckle, certainly, but they are also thoroughly dog-tired, whipped features, spent forces rather than self-propagating fires of combustion.  With Dunkirk making the rounds and tearing up the critics, I’ve decided to review a few (better) alternative WWII films that are not part of the official war film canon, or experience delayed entry to the minds of the public. Saving Private Ryan need not apply.

With Dunkirk making the rounds and tearing up the critics, I’ve decided to review a few (better) alternative WWII films that are not part of the official war film canon, or experience delayed entry to the minds of the public. Saving Private Ryan need not apply.  If nothing else, Sofia Coppola’s remake of Don Siegel’s tempestuous 1971 backwoods thriller of the same name is a valuable reflection of how the much-mocked “remake” status can be an opportunity to confront and a possibility to fulfill rather than merely a box to check if the film in question is not a sycophantic and slavish devotee to the original. Coppola’s new version of this story is no acolyte of Siegel’s, borrowing the plot and nothing of the mood, feel, style, or sensibility of the original. It’s still the story of a mostly-empty Civil War-era Southern girl’s school headed by Miss Martha Farnsworth (Nicole Kidman) and teacher Edwina Morrow (Kirsten Dunst) and the sexual emotions they stir when they take in wounded Union Corporal John McBurney (Colin Farrell) and help him back to health. (The other primary occupants of the school are a handful of youths, the most important in this version being Alicia (Elle Fanning), Jane (Angourie Rice), and Amy (Oona Laurence)). But if Siegel’s film was a moonshine-fueled folk tale, Coppola’s is a diorama fairy tale. While it doesn’t necessarily better the original, it does not copy it.

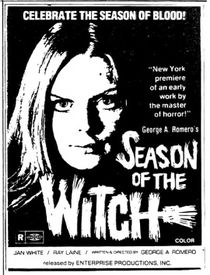

If nothing else, Sofia Coppola’s remake of Don Siegel’s tempestuous 1971 backwoods thriller of the same name is a valuable reflection of how the much-mocked “remake” status can be an opportunity to confront and a possibility to fulfill rather than merely a box to check if the film in question is not a sycophantic and slavish devotee to the original. Coppola’s new version of this story is no acolyte of Siegel’s, borrowing the plot and nothing of the mood, feel, style, or sensibility of the original. It’s still the story of a mostly-empty Civil War-era Southern girl’s school headed by Miss Martha Farnsworth (Nicole Kidman) and teacher Edwina Morrow (Kirsten Dunst) and the sexual emotions they stir when they take in wounded Union Corporal John McBurney (Colin Farrell) and help him back to health. (The other primary occupants of the school are a handful of youths, the most important in this version being Alicia (Elle Fanning), Jane (Angourie Rice), and Amy (Oona Laurence)). But if Siegel’s film was a moonshine-fueled folk tale, Coppola’s is a diorama fairy tale. While it doesn’t necessarily better the original, it does not copy it.  Season of the Witch

Season of the Witch I can think of hundreds of better films, but Face/Off is some kind of zenith, like a pure slab of movie-making distilled. Beyond being a gleefully trashy amped-up B-movie delight, as gloriously dysfunctional as it is intoxicatingly sure-handed, John Woo’s best (and only good) American film is a blockbuster treatise on the nature of identity, the only American picture he handled that remains truly permissive to his personal predilection for films about the dualistic nature of identity and the loss and retention of self. Hard Target (dementedly designed climax aside), Broken Arrow, Mission Impossible II, and certainly Windtalkers and the abominably luke-warm Paycheck all feel like imposters, but Face/Off has the special sauce, that auteurist alacrity and deliciously eccentric sense of self that only Woo could bring to a production like this. Nervously coiled interpersonal drama interpolated with orgasmic explosions of pressured-violence, this radioactive tangle of a film is exultant movie-making from beginning to end.

I can think of hundreds of better films, but Face/Off is some kind of zenith, like a pure slab of movie-making distilled. Beyond being a gleefully trashy amped-up B-movie delight, as gloriously dysfunctional as it is intoxicatingly sure-handed, John Woo’s best (and only good) American film is a blockbuster treatise on the nature of identity, the only American picture he handled that remains truly permissive to his personal predilection for films about the dualistic nature of identity and the loss and retention of self. Hard Target (dementedly designed climax aside), Broken Arrow, Mission Impossible II, and certainly Windtalkers and the abominably luke-warm Paycheck all feel like imposters, but Face/Off has the special sauce, that auteurist alacrity and deliciously eccentric sense of self that only Woo could bring to a production like this. Nervously coiled interpersonal drama interpolated with orgasmic explosions of pressured-violence, this radioactive tangle of a film is exultant movie-making from beginning to end. I know I should stop beating the dead horse of The Untouchables (it just doesn’t kick enough to truly live), but, Raising Cain? Now we’re talking. Five years after The Untouchables, and De Palma is back where he belongs: up to no good. Vigorously so, at that. Taking a sabbatical from tent-pole films (to be resumed soon enough with Carlito’s Way and, of course, Mission Impossible), Cain is a full-throated, fully-equipped expressionistic cluster-bomb of De Palma’s stylistic slipperiness, throwing his outre configurations of canted, dubious-perspective angles at us like a self-propagating fire. Avoiding any pretense of a sympathetic protagonist or a moral opponent for main character Dr. Nix (John Lithgow), Raising Cain lives up to its riotous name and then some.

I know I should stop beating the dead horse of The Untouchables (it just doesn’t kick enough to truly live), but, Raising Cain? Now we’re talking. Five years after The Untouchables, and De Palma is back where he belongs: up to no good. Vigorously so, at that. Taking a sabbatical from tent-pole films (to be resumed soon enough with Carlito’s Way and, of course, Mission Impossible), Cain is a full-throated, fully-equipped expressionistic cluster-bomb of De Palma’s stylistic slipperiness, throwing his outre configurations of canted, dubious-perspective angles at us like a self-propagating fire. Avoiding any pretense of a sympathetic protagonist or a moral opponent for main character Dr. Nix (John Lithgow), Raising Cain lives up to its riotous name and then some. The depressing timidity of Brian De Palma’s mercenary The Untouchables, a paycheck directorial role if ever there was one, is consummated in the centerpiece sequence, a verbatim riff on the famous staircase rumble and tumble from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (which was itself not as good as anything in Eisenstein’s prior film Strike). De Palma’s version is technically proficient – maybe even perfect – but purposeless and entirely rudimentary, excoriated of Eisenstein’s surrealistic flourishes and political-revolution tectonics. De Palma’s detractors tend to think of him as a Hitchcock plagiarist who debases that cinematic master of the macabre, but their argument falls apart when De Palma’s hedonistic formal pirouettes and wry, audience-blackmailing comic filigrees push Hitchcock way over the sanity edge. For scholars who ghettoize De Palma as a copy-cat and a reduction-artist, the real lynchpin of their argument should be The Untouchables, which repeats Eisenstein only to render him null and void.

The depressing timidity of Brian De Palma’s mercenary The Untouchables, a paycheck directorial role if ever there was one, is consummated in the centerpiece sequence, a verbatim riff on the famous staircase rumble and tumble from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (which was itself not as good as anything in Eisenstein’s prior film Strike). De Palma’s version is technically proficient – maybe even perfect – but purposeless and entirely rudimentary, excoriated of Eisenstein’s surrealistic flourishes and political-revolution tectonics. De Palma’s detractors tend to think of him as a Hitchcock plagiarist who debases that cinematic master of the macabre, but their argument falls apart when De Palma’s hedonistic formal pirouettes and wry, audience-blackmailing comic filigrees push Hitchcock way over the sanity edge. For scholars who ghettoize De Palma as a copy-cat and a reduction-artist, the real lynchpin of their argument should be The Untouchables, which repeats Eisenstein only to render him null and void.  Admirably quaint but radiating a felt force that can puncture all, David Lowery’s kiddie-Malick concoction benefits from that good old country comfort, from a deep resonance for quiet majesty. Lowery doesn’t inherit director Terrence Malick’s radical revisionism of American narrative tropes, but his fractured fairy tale debut Ain’t Them Bodies Saints carried the residue of Malick’s sensitive and innocently mature visual poetry taken from the American Western canon. That debut also suggested Lowery’s way with Malick’s beguilingly understated melodrama (a cinematic oxymoron if ever there was one) and his pseudo-impressionistic blend of modernism and traditionalism, a tone matched by few directors this side of David Gordon Green. Pete’s Dragon, Lowery’s follow-up, similarly feels both bred in the 1950s and essentially out-of-this-world, displaced from time. It is less aggressively painterly than Saints, to pull out the most over-used adjective in the critic’s canon, but no less silently magisterial. If push came to shove, I’d say the debut was the superior film, but Pete’s Dragon extends Lowery’s philosophy to the mainstream with admirable restraint and melancholy.

Admirably quaint but radiating a felt force that can puncture all, David Lowery’s kiddie-Malick concoction benefits from that good old country comfort, from a deep resonance for quiet majesty. Lowery doesn’t inherit director Terrence Malick’s radical revisionism of American narrative tropes, but his fractured fairy tale debut Ain’t Them Bodies Saints carried the residue of Malick’s sensitive and innocently mature visual poetry taken from the American Western canon. That debut also suggested Lowery’s way with Malick’s beguilingly understated melodrama (a cinematic oxymoron if ever there was one) and his pseudo-impressionistic blend of modernism and traditionalism, a tone matched by few directors this side of David Gordon Green. Pete’s Dragon, Lowery’s follow-up, similarly feels both bred in the 1950s and essentially out-of-this-world, displaced from time. It is less aggressively painterly than Saints, to pull out the most over-used adjective in the critic’s canon, but no less silently magisterial. If push came to shove, I’d say the debut was the superior film, but Pete’s Dragon extends Lowery’s philosophy to the mainstream with admirable restraint and melancholy.  Insofar as Netflix’s Castlevania “television show” is a wobbly forward half-step for video-game adaptations, it is because of its commitment to unbottling the aesthetic-first spirit of classical video gaming and relishing the principles of form, geometry, and negative space, all brandished here with a suitably diabolical disposition. If nothing more, it makes a convincing case for animation as the obvious cinematic corollary to video gaming.

Insofar as Netflix’s Castlevania “television show” is a wobbly forward half-step for video-game adaptations, it is because of its commitment to unbottling the aesthetic-first spirit of classical video gaming and relishing the principles of form, geometry, and negative space, all brandished here with a suitably diabolical disposition. If nothing more, it makes a convincing case for animation as the obvious cinematic corollary to video gaming.