A little old-timey cartoon before a feature for you all.

Chicken Little

Chicken Little

This irascible little Disney wartime devil is almost absurdly superior to that most fell semi-remake by the same company in 2005 (their first, and by far worst, CG feature film). Recasting the ignorance of youthful Chicken Little as the conscious social disruption of a fox who utilizes propaganda to convince everyone that the sky is falling, Chicken Little is a scabrous wartime cartoon about the dangers of Nazi (and Communist) propaganda that, implicitly, critiques its own vessel. The fox eventually sending all the none-the-wiser chickens to a cave (a bomb shelter, basically), all the better to eat them with, the film explores its own construction. With an inter-title at one point informing us that everything ends up okay in the end, the film concludes by pausing itself for a second to critique its own ending, with the narrator wondering aloud how the prior inter-title could lie to us; the Fox – mordantly laying chicken bones in graves like tombstones – informs the narrator and us not to believe everything we read. Continue reading

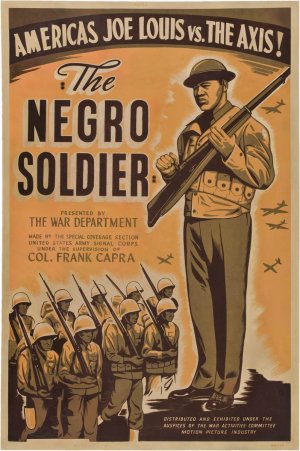

Defanging the shroud of mystical primitivism cast over African-Americans while also recasting black America as the spiritual center of American modernity, The Negro Soldier is simultaneously mildly hat-tip-able and deeply troubling in its propagandistic ideological concoction of egalitarian American opportunity for even the darkest and most neglected among us. Of the Frank Capra school of not-untroubled but always plausible American possibility, The Negro Soldier is one of the more documented “Why We Fight”-adjacent films even seventy years later, and also among the more inescapably despicable in its morally compromising sanding-over of racially-fraught American history in the name of the kind of hermetically-sealed war-time inclusiveness that only exists … well, it only exist in the motion pictures, as they say. This is the American road to freedom, with no pothole large or oppressive enough for Capra not to blanket over in warmth and saccharine sweetness (of course, a blanket isn’t going to stop you from falling into the American nightmare of racism if you get a little too close to reality for Capra’s comfort). One wonders what hell the devil John Huston would have wrought for one of his wartime propaganda films…

Defanging the shroud of mystical primitivism cast over African-Americans while also recasting black America as the spiritual center of American modernity, The Negro Soldier is simultaneously mildly hat-tip-able and deeply troubling in its propagandistic ideological concoction of egalitarian American opportunity for even the darkest and most neglected among us. Of the Frank Capra school of not-untroubled but always plausible American possibility, The Negro Soldier is one of the more documented “Why We Fight”-adjacent films even seventy years later, and also among the more inescapably despicable in its morally compromising sanding-over of racially-fraught American history in the name of the kind of hermetically-sealed war-time inclusiveness that only exists … well, it only exist in the motion pictures, as they say. This is the American road to freedom, with no pothole large or oppressive enough for Capra not to blanket over in warmth and saccharine sweetness (of course, a blanket isn’t going to stop you from falling into the American nightmare of racism if you get a little too close to reality for Capra’s comfort). One wonders what hell the devil John Huston would have wrought for one of his wartime propaganda films…  Rough-hewn and reticent, Jeff Nichols’ Midnight Special might inspire expected memories of Steven Spielberg’s and John Carpenter’s late ‘70s, early ‘80s science fiction films, but only if they were caught on the branches of a David Gordon Green feature. Evoking rustic pastoralism and never erring from Nichols’ customary Southern expanses, the feints toward the supernatural hardly suggest genre sell-out for a director who continues to mutate and evolve his perennial cinematic acts of high-tailing from urban (and suburban) civilization. Exploring the out-of-the-way places Nichols calls home, Midnight Special’s variant of “alien civilization” isn’t found in outer-space or the far-flung future but right in American backyards. If you know where you’re looking of course, and, say what you will about Nichols, but he not only knows the spots, but he’s got an eye on him.

Rough-hewn and reticent, Jeff Nichols’ Midnight Special might inspire expected memories of Steven Spielberg’s and John Carpenter’s late ‘70s, early ‘80s science fiction films, but only if they were caught on the branches of a David Gordon Green feature. Evoking rustic pastoralism and never erring from Nichols’ customary Southern expanses, the feints toward the supernatural hardly suggest genre sell-out for a director who continues to mutate and evolve his perennial cinematic acts of high-tailing from urban (and suburban) civilization. Exploring the out-of-the-way places Nichols calls home, Midnight Special’s variant of “alien civilization” isn’t found in outer-space or the far-flung future but right in American backyards. If you know where you’re looking of course, and, say what you will about Nichols, but he not only knows the spots, but he’s got an eye on him.  Deeply, unremittingly accepting John Huston’s blithely woozy, boozed-out vibe in full flourish, the strung-out, rampaging The Night of the Iguana is probably a little farcical in its over-heatedness. But then, this is Tennessee Williams. At least we’re in the presence of a full-throated, deviant, near-hallucinogenic dive into haughty, drunken melodrama, much more synonymous with the post-Faulkner Southern-modernist Williams spirit than most other Williams adaptations, usually quasi-heated chamber pieces vaguely tied to false-naturalism. In comparison, Iguana is unapologetic and viciously lacking in timidity, rejecting the half-hearted naturalistic ticks of most Williams adaptations for a merry expression of demented, licentious, sinful goodwill. Unlike, say, the good but overrated A Streetcar Named Desire, where the Method acting bug (as it often did) turned performance into a calculated private experiment rather than a vocally external art, The Night of the Iguana isn’t afraid to be to-the-rafters cinema. Baldly, even oppressively cinematic, it treats the brambles of melodrama as a wellspring of possibility to wrap itself in rather than as a shopworn, past-its-prime memory of Old Hollywood to skirt around.

Deeply, unremittingly accepting John Huston’s blithely woozy, boozed-out vibe in full flourish, the strung-out, rampaging The Night of the Iguana is probably a little farcical in its over-heatedness. But then, this is Tennessee Williams. At least we’re in the presence of a full-throated, deviant, near-hallucinogenic dive into haughty, drunken melodrama, much more synonymous with the post-Faulkner Southern-modernist Williams spirit than most other Williams adaptations, usually quasi-heated chamber pieces vaguely tied to false-naturalism. In comparison, Iguana is unapologetic and viciously lacking in timidity, rejecting the half-hearted naturalistic ticks of most Williams adaptations for a merry expression of demented, licentious, sinful goodwill. Unlike, say, the good but overrated A Streetcar Named Desire, where the Method acting bug (as it often did) turned performance into a calculated private experiment rather than a vocally external art, The Night of the Iguana isn’t afraid to be to-the-rafters cinema. Baldly, even oppressively cinematic, it treats the brambles of melodrama as a wellspring of possibility to wrap itself in rather than as a shopworn, past-its-prime memory of Old Hollywood to skirt around.  With The Little Prince on Netflix these days and Kubo and the Two Strings out soon enough, stop motion is making a comeback. You know what that means.

With The Little Prince on Netflix these days and Kubo and the Two Strings out soon enough, stop motion is making a comeback. You know what that means. The Bourne Identity

The Bourne Identity The pictorial inclinations of King Hu’s rhapsodic camerawork in his monumental wuxia epic A Touch of Zen are his film’s most gilded gestures, but they are no mere poetic filigrees. Rather, Hu’s investment in the physical space of his film and the way that a camera and a mind can intake and reform space informs a conscious refusal on the director’s part to explore character drama in a vacuum. Without the crucible of bounding characters by the natural environments that often remain overlooked in the world of cinema, Hu suggests that person vs. person conflict may be tenuous and unresolvable; an understanding of the earth itself it necessary first. The illusory beauty in the frame often suggests a new perceptual realm beyond the typical threshold of human consciousness, as though we are peering into an ethereal plane of color and space that eludes humanity’s typical tasks and goals. Space is otherworldly here, but also tactile, exerting a magnetic pull on the characters who weather through frames as if attracted by the deception of an unknown specter in the air. Or as though they characters were being exhumed from their internal, civilized spaces – and metaphorically the confines of their internal minds – to confront the outside world, to explore new perspectives in a desperate quest for self-actualization.

The pictorial inclinations of King Hu’s rhapsodic camerawork in his monumental wuxia epic A Touch of Zen are his film’s most gilded gestures, but they are no mere poetic filigrees. Rather, Hu’s investment in the physical space of his film and the way that a camera and a mind can intake and reform space informs a conscious refusal on the director’s part to explore character drama in a vacuum. Without the crucible of bounding characters by the natural environments that often remain overlooked in the world of cinema, Hu suggests that person vs. person conflict may be tenuous and unresolvable; an understanding of the earth itself it necessary first. The illusory beauty in the frame often suggests a new perceptual realm beyond the typical threshold of human consciousness, as though we are peering into an ethereal plane of color and space that eludes humanity’s typical tasks and goals. Space is otherworldly here, but also tactile, exerting a magnetic pull on the characters who weather through frames as if attracted by the deception of an unknown specter in the air. Or as though they characters were being exhumed from their internal, civilized spaces – and metaphorically the confines of their internal minds – to confront the outside world, to explore new perspectives in a desperate quest for self-actualization.  I meant to get to these a few months ago, but they’ve lingered around. With Batman vs. Superman continuing Warner’s desperate investment in doing the Marvel/Disney thing, here’s a look at some franchise-fighters to have come before. A note: We’re keeping this literal this time, much as I wanted to get cheeky and include something like Kramer vs. Kramer.

I meant to get to these a few months ago, but they’ve lingered around. With Batman vs. Superman continuing Warner’s desperate investment in doing the Marvel/Disney thing, here’s a look at some franchise-fighters to have come before. A note: We’re keeping this literal this time, much as I wanted to get cheeky and include something like Kramer vs. Kramer.  Political scorn has embarrassed Forrest Gump for two decades now, with the most common source of critique being the film’s glimpse of the rise (or return) of the American right in the mid-’90s, a revolution led by Newt Gingrich, a Southerner like Gump, although a considerably more blustery one at that. The attacks aren’t unfair – for a film that sometimes aggrandizes itself on a second-by-second basis, its social conscious is valid critical fodder, and the film’s exclusionary attitude toward gender and racial unrest proposes an almost oblivious Southern wait-and-see gentility toward civil disobedience. Gump is in fact an almost willfully obedient motion picture, with its then-new-school technology a masquerade for its rigorous cinematic traditionalism.

Political scorn has embarrassed Forrest Gump for two decades now, with the most common source of critique being the film’s glimpse of the rise (or return) of the American right in the mid-’90s, a revolution led by Newt Gingrich, a Southerner like Gump, although a considerably more blustery one at that. The attacks aren’t unfair – for a film that sometimes aggrandizes itself on a second-by-second basis, its social conscious is valid critical fodder, and the film’s exclusionary attitude toward gender and racial unrest proposes an almost oblivious Southern wait-and-see gentility toward civil disobedience. Gump is in fact an almost willfully obedient motion picture, with its then-new-school technology a masquerade for its rigorous cinematic traditionalism.  I’ve decided to post shorter reviews of various films I’m seeing for the first time via courses I’m enrolled in.

I’ve decided to post shorter reviews of various films I’m seeing for the first time via courses I’m enrolled in.