A little old-timey cartoon before a feature for you all.

A little old-timey cartoon before a feature for you all.

Der Fuehrer’s Face

Among Disney’s most infamous cartoons, reapportioning Donald Duck as a reluctant Nazi, Der Fuehrer’s Face is gloriously disreputable and unexpectedly (or expectedly, if you’ve studied Disney’s early shorts) experimental in its exploration of desire, imagination, and fear. Casting our fine feathered friend as a Nazi conscript of sorts, Der Fuehrer’s Face coagulates around a broader question of the mechanization of the human consciousness not unlike Chaplin’s Modern Times. Donald is pushed and pulled around physical space, the old squash-and-stretch style manipulated to explore the liminal space between the existential terror of lacking consciousness and the comedic potential in upending similar notions of individual agency (after all, both comedy and horror are reactions to the uncanny, and what is more uncanny in our individual-fetishizing America than losing one’s willpower). Continue reading

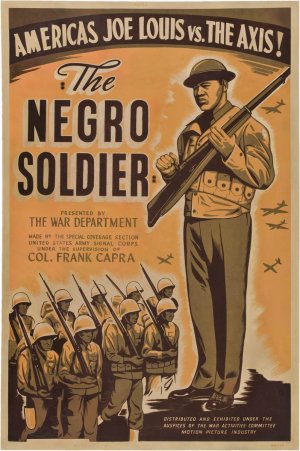

Defanging the shroud of mystical primitivism cast over African-Americans while also recasting black America as the spiritual center of American modernity, The Negro Soldier is simultaneously mildly hat-tip-able and deeply troubling in its propagandistic ideological concoction of egalitarian American opportunity for even the darkest and most neglected among us. Of the Frank Capra school of not-untroubled but always plausible American possibility, The Negro Soldier is one of the more documented “Why We Fight”-adjacent films even seventy years later, and also among the more inescapably despicable in its morally compromising sanding-over of racially-fraught American history in the name of the kind of hermetically-sealed war-time inclusiveness that only exists … well, it only exist in the motion pictures, as they say. This is the American road to freedom, with no pothole large or oppressive enough for Capra not to blanket over in warmth and saccharine sweetness (of course, a blanket isn’t going to stop you from falling into the American nightmare of racism if you get a little too close to reality for Capra’s comfort). One wonders what hell the devil John Huston would have wrought for one of his wartime propaganda films…

Defanging the shroud of mystical primitivism cast over African-Americans while also recasting black America as the spiritual center of American modernity, The Negro Soldier is simultaneously mildly hat-tip-able and deeply troubling in its propagandistic ideological concoction of egalitarian American opportunity for even the darkest and most neglected among us. Of the Frank Capra school of not-untroubled but always plausible American possibility, The Negro Soldier is one of the more documented “Why We Fight”-adjacent films even seventy years later, and also among the more inescapably despicable in its morally compromising sanding-over of racially-fraught American history in the name of the kind of hermetically-sealed war-time inclusiveness that only exists … well, it only exist in the motion pictures, as they say. This is the American road to freedom, with no pothole large or oppressive enough for Capra not to blanket over in warmth and saccharine sweetness (of course, a blanket isn’t going to stop you from falling into the American nightmare of racism if you get a little too close to reality for Capra’s comfort). One wonders what hell the devil John Huston would have wrought for one of his wartime propaganda films…  Mining conflicted stereotypes (alternately positive and negative and typically all of the above) of African-American culture wherein performance is nothing less than a fact of life and a principle of pure being, Stormy Weather reflects both WWII Hollywood’s sudden-onset awareness of black audiences and its indomitable drive to comb every inch of the American identity for souls to claim at the box office. Of course, this “sudden-onset awareness” was hardly circumstantial: with a significant portion of the movie-going audience abroad and embroiled in conflict (not that there wasn’t conflict on the homefront…) Hollywood suddenly discovered a reason to spread out its extremities in search of someone new to market to.

Mining conflicted stereotypes (alternately positive and negative and typically all of the above) of African-American culture wherein performance is nothing less than a fact of life and a principle of pure being, Stormy Weather reflects both WWII Hollywood’s sudden-onset awareness of black audiences and its indomitable drive to comb every inch of the American identity for souls to claim at the box office. Of course, this “sudden-onset awareness” was hardly circumstantial: with a significant portion of the movie-going audience abroad and embroiled in conflict (not that there wasn’t conflict on the homefront…) Hollywood suddenly discovered a reason to spread out its extremities in search of someone new to market to.  One doesn’t exactly go into a “Victor Fleming Production” and expect a kind of trashy wail covered in barbed wire. And one doesn’t get it with Red Dust, but it still feels like a specter from another world, the Pre-Code Hollywood world to be exact. In stark contrast to his one-two Gone with the Wind, Wizard of Oz punch in the most golden of Hollywood’s gilded years, 1939, the trim, rough-housed Red Dust never aspires to greatness, and as such, it is never strangled by an imaginative affinity with histrionic hyperbole run amok (the latter mode being MGM’s most cherished tone). Instead, this earthy, husky MGM film is a vortex of lusty, vulgar brashness and disreputable puncture wounds. Unfortunately, though, it’s all haunted over by the never-ending specter of colonialism in an Orientalist world authored by the West to serve as a presentational backdrop, even a manicured garden, for white subjects to battle out their own individual problems while towering over darker faces that are little more than part of the museum-quality scenery. I suppose you can’t change everything that was part of the conservative MGM claw.

One doesn’t exactly go into a “Victor Fleming Production” and expect a kind of trashy wail covered in barbed wire. And one doesn’t get it with Red Dust, but it still feels like a specter from another world, the Pre-Code Hollywood world to be exact. In stark contrast to his one-two Gone with the Wind, Wizard of Oz punch in the most golden of Hollywood’s gilded years, 1939, the trim, rough-housed Red Dust never aspires to greatness, and as such, it is never strangled by an imaginative affinity with histrionic hyperbole run amok (the latter mode being MGM’s most cherished tone). Instead, this earthy, husky MGM film is a vortex of lusty, vulgar brashness and disreputable puncture wounds. Unfortunately, though, it’s all haunted over by the never-ending specter of colonialism in an Orientalist world authored by the West to serve as a presentational backdrop, even a manicured garden, for white subjects to battle out their own individual problems while towering over darker faces that are little more than part of the museum-quality scenery. I suppose you can’t change everything that was part of the conservative MGM claw.  Seventy-six years on, The Grapes of Wrath’s star has faded noticeably, but it’s hardly been marginalized to the corners of cinematic history, even if the film explores the perverse marginalization of the American populace and the necrotization of an American dream mutilated beyond recognition. One would be surprised if a student of cinema meaningfully preferred this Best Picture winner over director John Ford’s masterful prior film, 1939’s Stagecoach (the best film from what many consider the most important year in American cinema, but that’s a story for another time). Hell, a thoughtful formalist might even prefer Ford’s next film, the frequently marginalized How Green Was My Valley (it’s no Citizen Kane, but what film is?). Still, square as it may be compared to the rebellious upstarts of the ‘70s and the hip young things of the American independent movement in the ‘50s, Ford’s incomparable skill for marshaling the formal principles of cinema for tales of plain-spoken, relatively unromantic Romanticism was usually untouched in the Classical era. If The Grapes of Wrath isn’t actually close to the apex of his career, it’s a sturdy and lyrical, if hardly revelatory, tapestry all the same.

Seventy-six years on, The Grapes of Wrath’s star has faded noticeably, but it’s hardly been marginalized to the corners of cinematic history, even if the film explores the perverse marginalization of the American populace and the necrotization of an American dream mutilated beyond recognition. One would be surprised if a student of cinema meaningfully preferred this Best Picture winner over director John Ford’s masterful prior film, 1939’s Stagecoach (the best film from what many consider the most important year in American cinema, but that’s a story for another time). Hell, a thoughtful formalist might even prefer Ford’s next film, the frequently marginalized How Green Was My Valley (it’s no Citizen Kane, but what film is?). Still, square as it may be compared to the rebellious upstarts of the ‘70s and the hip young things of the American independent movement in the ‘50s, Ford’s incomparable skill for marshaling the formal principles of cinema for tales of plain-spoken, relatively unromantic Romanticism was usually untouched in the Classical era. If The Grapes of Wrath isn’t actually close to the apex of his career, it’s a sturdy and lyrical, if hardly revelatory, tapestry all the same.  Crying foul on director Mikhail Kalatozov’s deliriously unhinged, masterful slice of post-Bay of Pigs agitprop for its unapologetic commitment to ideology would be tantamount to artistic heresy and limpid emphasis on the political over the artistic if the film weren’t such a bold and brazen reclamation of that age-old fact that art is innately political no matter what. Plunging into the revelry of fantastical space as obviously euphoric as Lang’s Metropolis city was demonic, and as bodaciously animated as Lang’s vision to boot, Yo Soy Cuba is an aesthetic vision primarily. But with these aesthetics, the proof is in the proverbial politics to begin with. Separating this far-out vision of a largely fictive representation of Cuban life from its animated muse – its Soviet morality – is at some level impossible: like Eisenstein’s utilization of montage to stage ideas of collective conflict, cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky’s aesthetic revolutions aren’t apolitical. Yo Soy Cuba is a vivacious workout, a Communist high palpably star-struck by the wave of political revolution it presumed (or hoped) was on the horizon, a film bathed in all the passions genuine belief can muster, and a work that marshals an unmediated, even crazed support for Cuban life into a catalyst for unbridled cinematic experimentation positively running wild with screw-loose charisma.

Crying foul on director Mikhail Kalatozov’s deliriously unhinged, masterful slice of post-Bay of Pigs agitprop for its unapologetic commitment to ideology would be tantamount to artistic heresy and limpid emphasis on the political over the artistic if the film weren’t such a bold and brazen reclamation of that age-old fact that art is innately political no matter what. Plunging into the revelry of fantastical space as obviously euphoric as Lang’s Metropolis city was demonic, and as bodaciously animated as Lang’s vision to boot, Yo Soy Cuba is an aesthetic vision primarily. But with these aesthetics, the proof is in the proverbial politics to begin with. Separating this far-out vision of a largely fictive representation of Cuban life from its animated muse – its Soviet morality – is at some level impossible: like Eisenstein’s utilization of montage to stage ideas of collective conflict, cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky’s aesthetic revolutions aren’t apolitical. Yo Soy Cuba is a vivacious workout, a Communist high palpably star-struck by the wave of political revolution it presumed (or hoped) was on the horizon, a film bathed in all the passions genuine belief can muster, and a work that marshals an unmediated, even crazed support for Cuban life into a catalyst for unbridled cinematic experimentation positively running wild with screw-loose charisma.  Simultaneously reaching a near artistic zenith and floundering in middling commercial anonymity with the giddy, off its rocker, positively deranged Bringing Up Baby in 1938, director Howard Hawks had obviously caught an itch that could not be quelled by merely retreating to a new genre (although Hawks was one of the foremost masters of genre-agnosticism in film history). Conscripting the dastardly trio of Charles Lederer, Ben Hecht, and Charles MacArthur to whip up a whirlygust of a screenplay conjured from the bones of the stageplay The Front Page (by the latter two of the trio), Hawks required another at bat for the genre. The progeny of this attempt, His Girl Friday, isn’t inherently the best Hawks film (it isn’t even the best Hawks screwball in my estimation). But as his second-chance screwball, it is the summit of his decade-long experimentation with the disconcerting, rebellious limits and possibilities of film sound.

Simultaneously reaching a near artistic zenith and floundering in middling commercial anonymity with the giddy, off its rocker, positively deranged Bringing Up Baby in 1938, director Howard Hawks had obviously caught an itch that could not be quelled by merely retreating to a new genre (although Hawks was one of the foremost masters of genre-agnosticism in film history). Conscripting the dastardly trio of Charles Lederer, Ben Hecht, and Charles MacArthur to whip up a whirlygust of a screenplay conjured from the bones of the stageplay The Front Page (by the latter two of the trio), Hawks required another at bat for the genre. The progeny of this attempt, His Girl Friday, isn’t inherently the best Hawks film (it isn’t even the best Hawks screwball in my estimation). But as his second-chance screwball, it is the summit of his decade-long experimentation with the disconcerting, rebellious limits and possibilities of film sound.  An aberration of the soon-to-be-implemented, puritanical Hays Code, Howard Hawks’ twitchy, rough-housed Scarface is a coarse rampage of firebrand cinematic verve, a sojourn into the underworld and death that paradoxically and perversely reflects cinema at its liveliest. Early sound cinema is often (falsely) denied vitality and dismissed as stodgy, but Scarface has a bullet or two to quell those who would deny it. Independently financed by Howard Hughes, Scarface trumpets its independent spirit as an ambivalently trashy social expose that wears its heart and its brain on its pistol. Cinema in the raw, it displays casual mastery of technique but invokes the shambolic one-take sloppiness of a killer Neil Young album.

An aberration of the soon-to-be-implemented, puritanical Hays Code, Howard Hawks’ twitchy, rough-housed Scarface is a coarse rampage of firebrand cinematic verve, a sojourn into the underworld and death that paradoxically and perversely reflects cinema at its liveliest. Early sound cinema is often (falsely) denied vitality and dismissed as stodgy, but Scarface has a bullet or two to quell those who would deny it. Independently financed by Howard Hughes, Scarface trumpets its independent spirit as an ambivalently trashy social expose that wears its heart and its brain on its pistol. Cinema in the raw, it displays casual mastery of technique but invokes the shambolic one-take sloppiness of a killer Neil Young album.  In the early golden years of classical Hollywood, Universal Studios somehow always tempted, and summarily avoided, being left hanging in the lurch. Unlike the five major studios, all of which owned their own theaters and thus guaranteed distribution of their films, Universal wasn’t born with a silver spoon in its mouth. The spendthrift glamour of the MGM musical machine was but a cloudy daydream for a studio that, while hardly poverty row, needed to carve out its own niche to go toe to toe with the big boys. Rather than trying to assimilate to the studio heavies with facsimiles of their Dream Factory productions, Universal ensconced itself in the out-of-the-way places, the boondocks of cinema, testing out more unsavory realms befitting their more hardscrabble existence. Unwilling, or unable, to lull the masses with luxuriant A-picture opulence, the company decided not to soothe America to bed but to lower itself into the murk of mutated German Expressionism and raise a shrieking countermelody, the kind of rattling cadence that could wake the dead.

In the early golden years of classical Hollywood, Universal Studios somehow always tempted, and summarily avoided, being left hanging in the lurch. Unlike the five major studios, all of which owned their own theaters and thus guaranteed distribution of their films, Universal wasn’t born with a silver spoon in its mouth. The spendthrift glamour of the MGM musical machine was but a cloudy daydream for a studio that, while hardly poverty row, needed to carve out its own niche to go toe to toe with the big boys. Rather than trying to assimilate to the studio heavies with facsimiles of their Dream Factory productions, Universal ensconced itself in the out-of-the-way places, the boondocks of cinema, testing out more unsavory realms befitting their more hardscrabble existence. Unwilling, or unable, to lull the masses with luxuriant A-picture opulence, the company decided not to soothe America to bed but to lower itself into the murk of mutated German Expressionism and raise a shrieking countermelody, the kind of rattling cadence that could wake the dead. Possibly the most explicitly thematic among the famously un-explicit Terrence Malick oeuvre, The New World’s de facto state of mind is the untamable wonder and bedeviling awe of the unexplored tracts of physical land and the unexplored mental topography of human longing and desire. Beginning with a human marooned in a strange world, the man’s only outlet to reformulate their essence is to couple the corporeal material of the physical world with his spiritual or extra-real essence of self-awareness within nature for the first time. This rigid “physical” and “mental/emotional/spiritual” dichotomy has historically been if not eroded then at least imperiled by non-Western cultures who have often adopted more fluxional conceptions of how physical, mental, and spiritual Western categorizations are instead more dialectical and interweaving, even possibly the same thing (materials are given use value beyond their capitalist physical money value). Malick’s own temperament has for decades obviously occupied a realm at least parallel to this distinctly non-capitalist mental wavelength. His films unstitch the iron-clad demarcations of the physical and the spiritual by basking in the ability of the human, untethered from their normative mental shackles, to approach new mental resplendence, new mental exultancy, by opening up to the capacious confines of the natural world.

Possibly the most explicitly thematic among the famously un-explicit Terrence Malick oeuvre, The New World’s de facto state of mind is the untamable wonder and bedeviling awe of the unexplored tracts of physical land and the unexplored mental topography of human longing and desire. Beginning with a human marooned in a strange world, the man’s only outlet to reformulate their essence is to couple the corporeal material of the physical world with his spiritual or extra-real essence of self-awareness within nature for the first time. This rigid “physical” and “mental/emotional/spiritual” dichotomy has historically been if not eroded then at least imperiled by non-Western cultures who have often adopted more fluxional conceptions of how physical, mental, and spiritual Western categorizations are instead more dialectical and interweaving, even possibly the same thing (materials are given use value beyond their capitalist physical money value). Malick’s own temperament has for decades obviously occupied a realm at least parallel to this distinctly non-capitalist mental wavelength. His films unstitch the iron-clad demarcations of the physical and the spiritual by basking in the ability of the human, untethered from their normative mental shackles, to approach new mental resplendence, new mental exultancy, by opening up to the capacious confines of the natural world.