One might think TCM2 is an obvious proposition: director Tobe Hooper attempting to escape the dark days of artistic poverty known as the ‘80s by returning to his most demonic days, forging a communion with the film devil and resurrecting the zombified corpse of his most famous film, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. But TCM2’s is no sycophant wearing its father’s clothes; more like a renegade fugitive dressing up like a horror film to throw the authorities off its trail. It is its predecessor’s polar opposite, as overt a case of a cinematic progeny rebelling against its parent with youthful indiscretion as the medium has ever birthed. Anticipating the devil-may-care comic mania of The Evil Dead 2 with as much brio but much less skill, Tobe Hooper’s sequel to his most famous film at least deserves points for attempting – rather openly – to misdiagnose its predecessors’ successes and run around in its own bizarre head-trip version of the original. An overt comedy, the film’s combustible zaniness is spirited even if it isn’t really inspired, and it sometimes feels like a colossally misjudged entity that is worth seeing only for the courage with which it misjudges itself. The quasi avant-garde set design and the ludicrous, anarchic disinterest in conventional mood skeletons mark Texas Chainsaw 2 as a fugitive inferno of sustained weirdness.

One might think TCM2 is an obvious proposition: director Tobe Hooper attempting to escape the dark days of artistic poverty known as the ‘80s by returning to his most demonic days, forging a communion with the film devil and resurrecting the zombified corpse of his most famous film, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. But TCM2’s is no sycophant wearing its father’s clothes; more like a renegade fugitive dressing up like a horror film to throw the authorities off its trail. It is its predecessor’s polar opposite, as overt a case of a cinematic progeny rebelling against its parent with youthful indiscretion as the medium has ever birthed. Anticipating the devil-may-care comic mania of The Evil Dead 2 with as much brio but much less skill, Tobe Hooper’s sequel to his most famous film at least deserves points for attempting – rather openly – to misdiagnose its predecessors’ successes and run around in its own bizarre head-trip version of the original. An overt comedy, the film’s combustible zaniness is spirited even if it isn’t really inspired, and it sometimes feels like a colossally misjudged entity that is worth seeing only for the courage with which it misjudges itself. The quasi avant-garde set design and the ludicrous, anarchic disinterest in conventional mood skeletons mark Texas Chainsaw 2 as a fugitive inferno of sustained weirdness.

Which is not the same thing as a good film, simply a potent one. Ripe and sour in equal measure, TCM 2’s basic line of attack is to inflate the corpse of its predecessor with noxious laughing gas until it explodes, toppling to the ground in chaotic convulsions of violence and beguilingly standoffish comedy. At the least, it has an identity – as baroque and strangely misguided as it can be – that is not synonymous with the dredged-in slasher glut so thick on the ground in the ‘80s. Possibly aware that the genre was waning (it was already on the way out by 1986, when TCM 2 was released), it at least diffuses the general tepidness of the genre and indulges in the incredibly toxic potencies of producers Golan and Globus, the most notorious producers of the ‘80s, responsible for a proper murderer’s row of cinematic monstrosities. Faced with the choice of going bad or going middle-of-the-road, let no one say the film wasn’t courageous. Proceed at your own peril. Continue reading

With the untimely passing of another horror icon, a quick look at a few of his films that aren’t *that one*.

With the untimely passing of another horror icon, a quick look at a few of his films that aren’t *that one*.  An astonishingly hopeless anti-myth odorized with the stench of failure and bloodstained with the tattered remains of hope, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? twists the idiom of dance away from its usual home in restless fantasy, treating human gyrations as the small-scale reverberations of a slowly-tilting edifice ready to crumble to the ground. For Sydney Pollock’s film, dance movements are first particles of movement that exist not to fling us into a hopeful future but to topple us from below, subsuming us to the movement of our feet that seem no longer tied to our minds or our personal agencies. Our bodies are no longer uncertain adventurers carving out a bold future but frantic chasers of a dream deferred, hoping to catch up to the scraps of nothingness thrown our way. They Shoot Horses is a parable of America as a collection of lost souls wandering into dancehall marathons – brandishing hopes and dreams of Grace Kelly and Fred Astaire, or the Charleston – and succumbing to the barren, unforgiving economic destitution that undergird and consume the romantic aspirations that nominally lacquer the surface of these activities. As Pollock sees it, bone-dragging, fall-out-of-bed-and-stumble-upwards days are the only ones America had in the ‘30s, and maybe ever again.

An astonishingly hopeless anti-myth odorized with the stench of failure and bloodstained with the tattered remains of hope, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? twists the idiom of dance away from its usual home in restless fantasy, treating human gyrations as the small-scale reverberations of a slowly-tilting edifice ready to crumble to the ground. For Sydney Pollock’s film, dance movements are first particles of movement that exist not to fling us into a hopeful future but to topple us from below, subsuming us to the movement of our feet that seem no longer tied to our minds or our personal agencies. Our bodies are no longer uncertain adventurers carving out a bold future but frantic chasers of a dream deferred, hoping to catch up to the scraps of nothingness thrown our way. They Shoot Horses is a parable of America as a collection of lost souls wandering into dancehall marathons – brandishing hopes and dreams of Grace Kelly and Fred Astaire, or the Charleston – and succumbing to the barren, unforgiving economic destitution that undergird and consume the romantic aspirations that nominally lacquer the surface of these activities. As Pollock sees it, bone-dragging, fall-out-of-bed-and-stumble-upwards days are the only ones America had in the ‘30s, and maybe ever again.  Sydney Pollock’s Jeremiah Johnson is, paradoxically, a resolutely, almost defiantly, old-school production, but it discovers a modernistic rejection of modernity in this very backward-looking milieu. As a Western, its interpretation of nature and mankind within it finds imaginative camaraderie with American art dating back to the Romantic painters of the mid-1800s who looked to nature – America’s bounty, they felt – to rebel against the earliest American painters, who mostly copied European high-art style, which codified as individualistic portraits lionizing heroic figures. These mid-1800s American painters, the first art rebels of the American vernacular, sought to uncouple themselves from European identity and establish a uniquely American sensibility. They found safe harbor in ruminating on, and enlarging the imaginative mythology of, the landscape, prophetically proposing – and thus clarifying into being – that America’s identity would be corporealized in the society-shunning, and paradoxically society-creating, individualism of a transient, undomesticated life on the road and through the forest.

Sydney Pollock’s Jeremiah Johnson is, paradoxically, a resolutely, almost defiantly, old-school production, but it discovers a modernistic rejection of modernity in this very backward-looking milieu. As a Western, its interpretation of nature and mankind within it finds imaginative camaraderie with American art dating back to the Romantic painters of the mid-1800s who looked to nature – America’s bounty, they felt – to rebel against the earliest American painters, who mostly copied European high-art style, which codified as individualistic portraits lionizing heroic figures. These mid-1800s American painters, the first art rebels of the American vernacular, sought to uncouple themselves from European identity and establish a uniquely American sensibility. They found safe harbor in ruminating on, and enlarging the imaginative mythology of, the landscape, prophetically proposing – and thus clarifying into being – that America’s identity would be corporealized in the society-shunning, and paradoxically society-creating, individualism of a transient, undomesticated life on the road and through the forest.  A new Annabelle sequel I haven’t seen is out; faced with the grim opportunity of reviewing its immediate predecessor, here is a much better killer doll film.

A new Annabelle sequel I haven’t seen is out; faced with the grim opportunity of reviewing its immediate predecessor, here is a much better killer doll film.  Queens of the Stone Age

Queens of the Stone Age The wide-ranging berth of writer-director Jia Zhangeke’s multipartite, all-across-China film, A Touch of Sin, cannot deny its impeccable eye for the specificity and complication of even the least of its individual tales. A Touch of Sin is obviously the story of a society; its nature is polyphonic, paralleling four individual tales and hinting at many others, asking us to look at a wider portrait of the world, even one in which many souls feel atomized and alienated. But, despite the length and size of this film, it never feels like a belabored or overly-grandiose obelisk, a sky-high statement that attempts to encompass all of China. Its rhythms are minute and intimate, its portrait of modern-day China finding its genesis not in any declamatory, macro-level statements but in the tight minutiae of four tales playing out on canvases of inward regret, internal dissolution, and people yearning for other selves.

The wide-ranging berth of writer-director Jia Zhangeke’s multipartite, all-across-China film, A Touch of Sin, cannot deny its impeccable eye for the specificity and complication of even the least of its individual tales. A Touch of Sin is obviously the story of a society; its nature is polyphonic, paralleling four individual tales and hinting at many others, asking us to look at a wider portrait of the world, even one in which many souls feel atomized and alienated. But, despite the length and size of this film, it never feels like a belabored or overly-grandiose obelisk, a sky-high statement that attempts to encompass all of China. Its rhythms are minute and intimate, its portrait of modern-day China finding its genesis not in any declamatory, macro-level statements but in the tight minutiae of four tales playing out on canvases of inward regret, internal dissolution, and people yearning for other selves.  It would be astonishingly difficult to convince a viewer to watch director Christi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu if they weren’t already predisposed to adore Puiu’s strange, sardonic, drunken but deeply compassionate 150-minute account of exactly what its title suggests. The plain-spoken brutality of the film’s title is not an ironic or even a metaphysical signpost for the symbolic scholar. It is not simply an imaginative foothold for the audience to understand that the film is really using its narrative to plumb some epochal commentary on life in modern-day Romania, to expose a “death” that is abstract or societal in nature, as though the world’s compassion is withering away. The title is not merely an intimation or a whispered poeticism, a literary flick of the pen meant to draw us into the film’s thematic caverns.

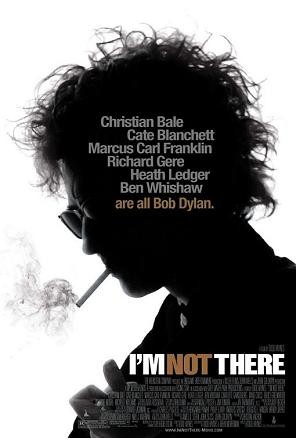

It would be astonishingly difficult to convince a viewer to watch director Christi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu if they weren’t already predisposed to adore Puiu’s strange, sardonic, drunken but deeply compassionate 150-minute account of exactly what its title suggests. The plain-spoken brutality of the film’s title is not an ironic or even a metaphysical signpost for the symbolic scholar. It is not simply an imaginative foothold for the audience to understand that the film is really using its narrative to plumb some epochal commentary on life in modern-day Romania, to expose a “death” that is abstract or societal in nature, as though the world’s compassion is withering away. The title is not merely an intimation or a whispered poeticism, a literary flick of the pen meant to draw us into the film’s thematic caverns.  A whirlygust of synapses fire, intellectually, emotionally, and sensually in director Todd Haynes’ thematic invocation of Bob Dylan, I’m Not There, which is a tone poem about Dylan as a concept, as an ache in the belly, as a mind for dissent, and as a troubadour that infects the minds of everyone willing to listen. It is not a picture about Dylan as a human being or a flesh-in-blood person, although it is defiant in its unabashed humanism, calling on a panoply of styles and personhoods to refract Dylan across numerous time spaces and identities to reveal not only his polyphonic self but the many valences of the nation he both represented and challenged. Dylan here is omnidirectional, paradoxically both a symbol for anything you want and a hungrier creature that swallows symbols whole and runs away in his (or her) own direction. Most biopics – a genre I’m Not There is only very tenuously related to – are a kind of pedestrian par excellance, as cinematically dead and intellectually bankrupt as any Michael Bay film, even though biopics wear their intellects less lightly and call on the spirit of the middlebrow rather than the lowbrow. They draw a decisive quotient of their beings from their belief that they can unravel and pin-down their subject-matter, that they are educators imparting true knowledge to the viewer. In contrast, I’m Not There cannot be pinned down, and it shows that its subject cannot either.

A whirlygust of synapses fire, intellectually, emotionally, and sensually in director Todd Haynes’ thematic invocation of Bob Dylan, I’m Not There, which is a tone poem about Dylan as a concept, as an ache in the belly, as a mind for dissent, and as a troubadour that infects the minds of everyone willing to listen. It is not a picture about Dylan as a human being or a flesh-in-blood person, although it is defiant in its unabashed humanism, calling on a panoply of styles and personhoods to refract Dylan across numerous time spaces and identities to reveal not only his polyphonic self but the many valences of the nation he both represented and challenged. Dylan here is omnidirectional, paradoxically both a symbol for anything you want and a hungrier creature that swallows symbols whole and runs away in his (or her) own direction. Most biopics – a genre I’m Not There is only very tenuously related to – are a kind of pedestrian par excellance, as cinematically dead and intellectually bankrupt as any Michael Bay film, even though biopics wear their intellects less lightly and call on the spirit of the middlebrow rather than the lowbrow. They draw a decisive quotient of their beings from their belief that they can unravel and pin-down their subject-matter, that they are educators imparting true knowledge to the viewer. In contrast, I’m Not There cannot be pinned down, and it shows that its subject cannot either.  Inhabiting a gradient from electrifyingly un-ironic romanticism to baleful malevolence to existential calamity, Jonathan Glazer’s follow-up to his debut Sexy Beast is subtle in its implication but implosive in touch, feel, sensation, and style. It hangs over you, with premonitions of doubt and stenches of inclement weather overhead, but it avoids many (most) of the easy tricks films use to evoke the shadows of modernity: expressionistic shadows, a thick gauze of lighting, canted angles. Many films today are embalmed in expectations and mental prisons for what horror might mean, and here is the fiercely alive Birth, an otherworldly film not because of the presence of diegetic aliens or space travel but because it confronts our world through an alternate perspective from the one most of us call home. Although its intellectual and sensory channels were undeniably forged from the ghostly modernistic vibes of Resnais and the self-inquiry of Antonioni, it nonetheless inhabits the frontiers of consciousness.

Inhabiting a gradient from electrifyingly un-ironic romanticism to baleful malevolence to existential calamity, Jonathan Glazer’s follow-up to his debut Sexy Beast is subtle in its implication but implosive in touch, feel, sensation, and style. It hangs over you, with premonitions of doubt and stenches of inclement weather overhead, but it avoids many (most) of the easy tricks films use to evoke the shadows of modernity: expressionistic shadows, a thick gauze of lighting, canted angles. Many films today are embalmed in expectations and mental prisons for what horror might mean, and here is the fiercely alive Birth, an otherworldly film not because of the presence of diegetic aliens or space travel but because it confronts our world through an alternate perspective from the one most of us call home. Although its intellectual and sensory channels were undeniably forged from the ghostly modernistic vibes of Resnais and the self-inquiry of Antonioni, it nonetheless inhabits the frontiers of consciousness.