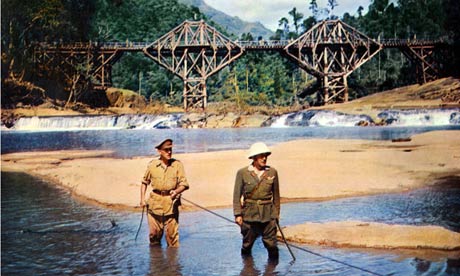

If The Bridge on the River Kwai is an inflection point in the bifurcated career of the most quintessentially British of all directors, David Lean, it is no victim of a split-decision. Emblazoned with both the staunchly intimate character focus of Lean’s earlier inspections of British life and the bellowing grandeur of his boldface later pictures, The Bridge on the River Kwai is a meeting of minds with a sweep that not only contrasts but amalgamates the luxuriant and the domestic. It lacks the fiercely enigmatic streak of Lean’s later Lawrence of Arabia – where delusions of self-immolating grandeur, imperialist mystique, and hot-headed rebellion conspire to denounce the essential vision of prodigious orientalism that sticks to Western cinema like a fly to excrement. But such concerns are valueless amidst Bridge’s vigorous cinematic workout and its scorching exegesis of the essential social codebook of Twentieth Century British life. Continue reading

If The Bridge on the River Kwai is an inflection point in the bifurcated career of the most quintessentially British of all directors, David Lean, it is no victim of a split-decision. Emblazoned with both the staunchly intimate character focus of Lean’s earlier inspections of British life and the bellowing grandeur of his boldface later pictures, The Bridge on the River Kwai is a meeting of minds with a sweep that not only contrasts but amalgamates the luxuriant and the domestic. It lacks the fiercely enigmatic streak of Lean’s later Lawrence of Arabia – where delusions of self-immolating grandeur, imperialist mystique, and hot-headed rebellion conspire to denounce the essential vision of prodigious orientalism that sticks to Western cinema like a fly to excrement. But such concerns are valueless amidst Bridge’s vigorous cinematic workout and its scorching exegesis of the essential social codebook of Twentieth Century British life. Continue reading

Monthly Archives: March 2016

Picturing the Best: Rebecca and How Green Was My Valley

Of all the Alfred Hitchcock films in existence, one shouldn’t feign surprise that it was Rebecca that was lovingly overcast with the radiant glow of the amber Oscar. Frankly, and as is often the case, the reality is that the singular Oscar glory was afforded to one of the more stolid, “respectable” pictures in the canon of a director that thrived when he was barreling away from respect at a hundred miles an hour. By the standards of sub-expressionist horror, mind you, Rebecca is plenty disturbed, with Hitch’s direction sterling and suffocating even if it’s less maverick and personal than it would be later in his career. But watching Rebecca, a ghoulishly charming little bedeviled jewel in bewilderingly trumped-up costume drama airs, it’s painfully obvious that he was playing mega-producer David O. Selznick’s mercenary at this point, and that the film’s Oscar glory is less a statement to any truly revolutionary or thought-provoking aims than to the sheer size of the film’s majesty. While Vertigo, Rear Window, Strangers on a Train, and a dozen other Hitch films animate wonderfully contradictory impulses to truly destabilizing ends, the only thing Rebecca animates is Selznick’s production budget. And the only thing it tests is the size of Selznick’s ego, his inimitable capacity to gild and ornament a competent husk of a film with all the production decorum his bottomless pockets could buy. Continue reading

Of all the Alfred Hitchcock films in existence, one shouldn’t feign surprise that it was Rebecca that was lovingly overcast with the radiant glow of the amber Oscar. Frankly, and as is often the case, the reality is that the singular Oscar glory was afforded to one of the more stolid, “respectable” pictures in the canon of a director that thrived when he was barreling away from respect at a hundred miles an hour. By the standards of sub-expressionist horror, mind you, Rebecca is plenty disturbed, with Hitch’s direction sterling and suffocating even if it’s less maverick and personal than it would be later in his career. But watching Rebecca, a ghoulishly charming little bedeviled jewel in bewilderingly trumped-up costume drama airs, it’s painfully obvious that he was playing mega-producer David O. Selznick’s mercenary at this point, and that the film’s Oscar glory is less a statement to any truly revolutionary or thought-provoking aims than to the sheer size of the film’s majesty. While Vertigo, Rear Window, Strangers on a Train, and a dozen other Hitch films animate wonderfully contradictory impulses to truly destabilizing ends, the only thing Rebecca animates is Selznick’s production budget. And the only thing it tests is the size of Selznick’s ego, his inimitable capacity to gild and ornament a competent husk of a film with all the production decorum his bottomless pockets could buy. Continue reading

Picturing the Best: It Happened One Night

It’s easy to reduce Frank Capra to a series of benighted adjectives of excessive sentimentality, markers of his supposedly clueless optimism in the face of pressing danger. But it’s wilder still to witness the willful disobedience of his early films, to evoke their blithe defiance of the dejected spirit of their times. While other directors were content to apply the “sound” eruption as a buttress to the burgeoning demand for cinematic “realism”, Capra’s spirit was to laugh in the face of crushing reality, to play within the confines of poverty and, in doing so, to trace the contours of not only national desperation but the everyday performers and players who resist it. In 1934, on the eve of his rise to gargantuan fame overnight, this meant upending the laissez-faire classism and degradation of opportunity in society, expelling a spitfire, screw-loose comedy that made mincemeat out of America’s aristocracy and paid homage to the zealous can-do Americana he fell in love with. Continue reading

It’s easy to reduce Frank Capra to a series of benighted adjectives of excessive sentimentality, markers of his supposedly clueless optimism in the face of pressing danger. But it’s wilder still to witness the willful disobedience of his early films, to evoke their blithe defiance of the dejected spirit of their times. While other directors were content to apply the “sound” eruption as a buttress to the burgeoning demand for cinematic “realism”, Capra’s spirit was to laugh in the face of crushing reality, to play within the confines of poverty and, in doing so, to trace the contours of not only national desperation but the everyday performers and players who resist it. In 1934, on the eve of his rise to gargantuan fame overnight, this meant upending the laissez-faire classism and degradation of opportunity in society, expelling a spitfire, screw-loose comedy that made mincemeat out of America’s aristocracy and paid homage to the zealous can-do Americana he fell in love with. Continue reading

Picturing the Best: All Quiet on the Western Front

I meant to get around to these a month ago, but you know. I guess time stands still for a now not-so-timely tour of historical Best Picture winners, with two reviews per full decade (meaning I’ve omitted the handful of years in the late ’20s because, I mean, I’ve already reviewed Sunrise). Generally, although not exclusively, they’ll be presented in pairs so as to keep the length down at a reasonable level. For the first decade, to salvage the horrors of one of the most useless superlative awards in the film world, I’ve decided to begin with the two instances that got it right.

I meant to get around to these a month ago, but you know. I guess time stands still for a now not-so-timely tour of historical Best Picture winners, with two reviews per full decade (meaning I’ve omitted the handful of years in the late ’20s because, I mean, I’ve already reviewed Sunrise). Generally, although not exclusively, they’ll be presented in pairs so as to keep the length down at a reasonable level. For the first decade, to salvage the horrors of one of the most useless superlative awards in the film world, I’ve decided to begin with the two instances that got it right.

The Pre-Code Hollywood era, although short-lived, is often wielded as a talking point for the unwound, comparatively flexible, nimble naughtiness of the early days of American sound film. And sure enough, brusque, punchy works like Scarface and I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang upended traditional mores and continue to shock audiences who build the perception bridge to classic cinema out of a mortar as inflexible as modern expectations about the gentle, naïve nature of early sound cinema. Continue reading

Films for Class: Harold and Maude

Despite nominally tenanting the early days of the New Hollywood, Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude achieves a frisky, mischievous barrel-house piano playfulness more at home with the mid-’60s works of Richard Lester, who made films masquerading as larks that nonetheless disobediently dissected society’s fascination with identity with a manic frivolity that both epitomized and upended the giddy image of the 1960s . Prefiguring and serving as an advance riposte to the grisly grottos of Scorsese and friends that embodied the dejected, askew stench of the 1970s, Harold and Maude reflects the unbridled romanticism of the hippie movement, a time before carefree mania was played in the frenzied register of abject pandemonium. Continue reading

Despite nominally tenanting the early days of the New Hollywood, Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude achieves a frisky, mischievous barrel-house piano playfulness more at home with the mid-’60s works of Richard Lester, who made films masquerading as larks that nonetheless disobediently dissected society’s fascination with identity with a manic frivolity that both epitomized and upended the giddy image of the 1960s . Prefiguring and serving as an advance riposte to the grisly grottos of Scorsese and friends that embodied the dejected, askew stench of the 1970s, Harold and Maude reflects the unbridled romanticism of the hippie movement, a time before carefree mania was played in the frenzied register of abject pandemonium. Continue reading

Film Favorites: The Sacrifice

Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film is not his greatest work, but with the weight of his passing hanging over the piece, it emerges as something even more notable, even more trenchant. The Sacrifice remains a foremost reminder that the cinema’s most pressing, most exploratory wanderer left the world the way he would want to: without an answer, still wandering and exploring. For, unlike most of Tarkovsky’s contemporaries (excepting maybe Terrence Malick in America), the Russian poet’s films defy answers, riddles, destinations, or arrivals. They laugh in the face of finalitude, they eschew completeness, they stage a coup against the idea of conclusion because their very caliber as cinema is inextricably tied not to the arrival at knowledge, as every other film stresses, but to mechanisms of knowing and to the experience of feeling. For Tarkovsky, how we sense the world is the divining rod to what we sense. Continue reading

Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film is not his greatest work, but with the weight of his passing hanging over the piece, it emerges as something even more notable, even more trenchant. The Sacrifice remains a foremost reminder that the cinema’s most pressing, most exploratory wanderer left the world the way he would want to: without an answer, still wandering and exploring. For, unlike most of Tarkovsky’s contemporaries (excepting maybe Terrence Malick in America), the Russian poet’s films defy answers, riddles, destinations, or arrivals. They laugh in the face of finalitude, they eschew completeness, they stage a coup against the idea of conclusion because their very caliber as cinema is inextricably tied not to the arrival at knowledge, as every other film stresses, but to mechanisms of knowing and to the experience of feeling. For Tarkovsky, how we sense the world is the divining rod to what we sense. Continue reading

Review: Zootopia

Although the tone of Zootopia is more buddy-cop than genuine neo-noir, the most startling, bracing moments of Disney’s newest blissful concoction are when the busy animation suffuses into sly dances of negative space and subfuscous, shady imagery. A nimble midnight fright dalliance to the rainforest district of the mega-city of Zootopia evokes memories of Val Lewton as it plays with impressionistic fog to visualize the hidden darkness and barely-subsumed discontent lingering in the hearts and minds of the vague, surface-level utopia the film is set in. The sequence, where the overbearing, cotton-candy lightness of the city is set adrift to reveal the brimming darkness lurking undertow, encapsulates the concealed friction and fissure underlying the post-racial visage of Zootopia. Continue reading

Although the tone of Zootopia is more buddy-cop than genuine neo-noir, the most startling, bracing moments of Disney’s newest blissful concoction are when the busy animation suffuses into sly dances of negative space and subfuscous, shady imagery. A nimble midnight fright dalliance to the rainforest district of the mega-city of Zootopia evokes memories of Val Lewton as it plays with impressionistic fog to visualize the hidden darkness and barely-subsumed discontent lingering in the hearts and minds of the vague, surface-level utopia the film is set in. The sequence, where the overbearing, cotton-candy lightness of the city is set adrift to reveal the brimming darkness lurking undertow, encapsulates the concealed friction and fissure underlying the post-racial visage of Zootopia. Continue reading

Review: Triple 9

Filmed in Atlanta and set in a New Englander’s nightmare vision of a Southern city contaminated with centuries of race and class disparity, Triple 9 at least deserves some credit for marinating its city with the grime and grotto typically reserved for world cities like New York. With images of the Big Peach still fraught by the oppressive genteel paternalism and antebellum haze of Gone with the Wind and the cringe-inducing respectability politics of Driving Miss Daisy, Triple 9 at least relies on the now cosmopolitan city to construct an identity out of more modern visions of race and class consternation. Triple 9 is not trapped in the streamlined racism of old, but fraught with the combative, confrontational contortions of a city that pummeled its way into the future while still remaining trapped in the past. Continue reading

Filmed in Atlanta and set in a New Englander’s nightmare vision of a Southern city contaminated with centuries of race and class disparity, Triple 9 at least deserves some credit for marinating its city with the grime and grotto typically reserved for world cities like New York. With images of the Big Peach still fraught by the oppressive genteel paternalism and antebellum haze of Gone with the Wind and the cringe-inducing respectability politics of Driving Miss Daisy, Triple 9 at least relies on the now cosmopolitan city to construct an identity out of more modern visions of race and class consternation. Triple 9 is not trapped in the streamlined racism of old, but fraught with the combative, confrontational contortions of a city that pummeled its way into the future while still remaining trapped in the past. Continue reading

Progenitors: Days of Heaven

Now that the release of Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups upon us, a review of his second film is in order.

Now that the release of Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups upon us, a review of his second film is in order.

With theme and character sublimated to the level of the gushingly sensory and a stream-of-consciousness structure that pronounces its own subjectivity, Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven is not only one of the defining works of cinematic experience but the closest that film form has come to replicating the semiotics of William Faulkner’s literary imagination. The outline of the narrative – laborer Bill (Richard Gere) courts Abby (Brooke Adams) and stages her marriage to land owner Farmer (Sam Shepard) in a ploy to escape their workaday miasma – is suffused with forlorn Southern atmosphere. But, as with Faulkner, the texture of Malick’s work is not explaining or exploring that narrative but rendering it untenable and deferential to fluid, impermanent figments of memory, perspective, and subjectivity. In both imaginations, experience is not – as in most fiction – assured and objective, but cursory, fugitive, and ultimately perhaps inestimable. Continue reading

Pop!: The Dirty Dozen

A pair of reviews from a series last year I never got around to publishing…

A pair of reviews from a series last year I never got around to publishing…

The Dirty Dozen, a war film perched on the cusp of the New Hollywood and preluding the obstreperous cynicism of the 1970s, feels like a new breed of war film more akin to the nasty, capricious revisionist Westerns waiting in the wings of the late ’60s. The film, directed by low-flying Hollywood stalwart Robert Aldrich, insulates itself from the stodgy, antiquated chamber-bound quality of most anti-war films by inducing a feral fit that, in the final third, explodes into an outright anxiety attack. Although military cruelty is on the mind, The Dirty Dozen is hardly a courtroom drama; befitting its brusque title, it’s a grubby grotto of unmanaged anger that sands itself down sometimes not to detach itself but to express the dehumanized, dispassionate nature of war altogether. Casting Lee Marvin in the role of a military commander tasked with training a motley crew of reprobates and military prisoners to dismantle and destroy a Nazi high command party on the eve of the D-Day invasion, Robert Aldrich’s film casts a ghostly pallor over the so-called last moral war by threatening it with its own essential amorality. Continue reading