If Orson Welles truly did pine for the spotlight, he was nevertheless often at his best devouring all-comers while occupying the fringes. Maybe it was his passive-aggressive drive that forced him into a corner. Maybe having to struggle for his reputation was purifying for him. Maybe having his own little corner of cinema fed his ego and controlling belligerence. Maybe he needed to be left out in the cold, so he could burn even more dangerously. Whatever the case, whether Welles actively retreated into the nether realms of independent cinema or was coerced to hibernate there, Welles never let go of his dream. Becoming a Hollywood outsider, if anything, only made him angrier and more loathsome, and loathsome Welles was Welles at his most playful. His self-serving grandeur and operatic diction could take on a pompous hue when he was already at the top, but when he was picking his battles from the outside, as with Mr. Arkadin, his directorial bravura actually seemed carnivorous and challenging, even combative. Working from the outside gave Welles something to fight for, and Welles with fangs drawn ready to pounce is the only real Welles in my book. Continue reading

If Orson Welles truly did pine for the spotlight, he was nevertheless often at his best devouring all-comers while occupying the fringes. Maybe it was his passive-aggressive drive that forced him into a corner. Maybe having to struggle for his reputation was purifying for him. Maybe having his own little corner of cinema fed his ego and controlling belligerence. Maybe he needed to be left out in the cold, so he could burn even more dangerously. Whatever the case, whether Welles actively retreated into the nether realms of independent cinema or was coerced to hibernate there, Welles never let go of his dream. Becoming a Hollywood outsider, if anything, only made him angrier and more loathsome, and loathsome Welles was Welles at his most playful. His self-serving grandeur and operatic diction could take on a pompous hue when he was already at the top, but when he was picking his battles from the outside, as with Mr. Arkadin, his directorial bravura actually seemed carnivorous and challenging, even combative. Working from the outside gave Welles something to fight for, and Welles with fangs drawn ready to pounce is the only real Welles in my book. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Blow-Up

As beautiful and scandalously masterful as it is, nothing about Blow-Up will ever be able to trump the sheer bafflement of its existence. In the mid ’60s, at the height of all that was swinging and buoyant and laconic about the decade’s concept of effortless cool and before that cool would curdle into something nasty and paranoid by the late ’60s, someone thought Michelangelo Antonioni, a film director even more cruel and formally intellectual and difficult than Fellini or even Godard, should direct a chipper, sex bombshell of a motion picture. I have no idea what promoted this happenstance, although I assume the swinging ’60s were just so off-kilter, the drugs so hazy and befuddling, that a movie producer just heard about that Antonioni guy who made “modernist” films and said “yes him, we need him to direct our ode to all that is chic about the mid-’60s”. Needless to say, they probably didn’t get the film they were expecting, but it made a cool 20 million anyway (huge in those days), and the producers were probably happy in the end. Continue reading

As beautiful and scandalously masterful as it is, nothing about Blow-Up will ever be able to trump the sheer bafflement of its existence. In the mid ’60s, at the height of all that was swinging and buoyant and laconic about the decade’s concept of effortless cool and before that cool would curdle into something nasty and paranoid by the late ’60s, someone thought Michelangelo Antonioni, a film director even more cruel and formally intellectual and difficult than Fellini or even Godard, should direct a chipper, sex bombshell of a motion picture. I have no idea what promoted this happenstance, although I assume the swinging ’60s were just so off-kilter, the drugs so hazy and befuddling, that a movie producer just heard about that Antonioni guy who made “modernist” films and said “yes him, we need him to direct our ode to all that is chic about the mid-’60s”. Needless to say, they probably didn’t get the film they were expecting, but it made a cool 20 million anyway (huge in those days), and the producers were probably happy in the end. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Chimes at Midnight

When we last encountered old Orson meddling around in the realm of the most respected English author ever to grace the Earth (Welles prone to giving odes from one auteur to another), he was content to do nothing less than reshape Othello’s vocabulary from the ground-up, trading barbed words for jagged angles and producing the most vivaciously visual Shakespeare adaptation ever released, and also arguably the best. Admittedly, Othello was something of a little slice of miracle, an accident turned into an avant-garde masterwork not only by Welles’ intent but by the simple fact that the film Welles set out to make was interrupted by budgetary constraints, reshoots, haphazard location hopping, non-linear shooting times that required the piece to be shot piecemeal over several years, and seemingly every other plague Welles could sick upon himself. We may never know what Welles intended Othello to be, but he turned every adverse occurrence into an advantage by making one of the great scrap heap guerrilla masterpieces of the cinema. Continue reading

When we last encountered old Orson meddling around in the realm of the most respected English author ever to grace the Earth (Welles prone to giving odes from one auteur to another), he was content to do nothing less than reshape Othello’s vocabulary from the ground-up, trading barbed words for jagged angles and producing the most vivaciously visual Shakespeare adaptation ever released, and also arguably the best. Admittedly, Othello was something of a little slice of miracle, an accident turned into an avant-garde masterwork not only by Welles’ intent but by the simple fact that the film Welles set out to make was interrupted by budgetary constraints, reshoots, haphazard location hopping, non-linear shooting times that required the piece to be shot piecemeal over several years, and seemingly every other plague Welles could sick upon himself. We may never know what Welles intended Othello to be, but he turned every adverse occurrence into an advantage by making one of the great scrap heap guerrilla masterpieces of the cinema. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Kwaidan

Any horror cinema enthusiast would do well to experience – to bathe, in fact – in the luscious spooks and rattling phantasmagoria of Japanese horror cinema in the 1960s. For fans of the genre, the only comparable historical periods for a nation’s horror cinema would be German horror in the 1920s and Italian horror in the ’70s. The German cinema topples anything for sheer awe and hanging-on dread, and the Italian cinema cannot be surpassed for pure maddening Grand Guignol calamity and grotesque, baroque, colorific ballets-of-blood. But, in terms of spectral atmosphere and cosmic displays of the painterly otherworlds lying just under the sheets of humankind’s darkest nightmares, Japanese horror cinema in the 1960s rises above any and all cinematic horror sub-groups for displaying the macabre in the most exquisite, transcendental, heavenly detail. Continue reading

Any horror cinema enthusiast would do well to experience – to bathe, in fact – in the luscious spooks and rattling phantasmagoria of Japanese horror cinema in the 1960s. For fans of the genre, the only comparable historical periods for a nation’s horror cinema would be German horror in the 1920s and Italian horror in the ’70s. The German cinema topples anything for sheer awe and hanging-on dread, and the Italian cinema cannot be surpassed for pure maddening Grand Guignol calamity and grotesque, baroque, colorific ballets-of-blood. But, in terms of spectral atmosphere and cosmic displays of the painterly otherworlds lying just under the sheets of humankind’s darkest nightmares, Japanese horror cinema in the 1960s rises above any and all cinematic horror sub-groups for displaying the macabre in the most exquisite, transcendental, heavenly detail. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

The de facto line about Jacques Demy’s bubbly musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is that it is so gleefully and willfully out of touch with the corpus of French New Wave films being released vociferously throughout the 1960s. This is a point of great merit. Compared to, say, Godard’s Breathless, Demy’s Cherbourg is a less cantankerous sort that is less tethered to being violently abusive to cinema. Demy, along with many of the Left Bank directors of the New Wave, was more classicist than someone like Godard to be sure, and he was less drawn to a critique of Hollywood styles. The spirit of defiant rejection of the defiant rejection of the New Wave is very much present and accounted for in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, as loving a tribute to the Hollywood musical as you could hope to find. Continue reading

The de facto line about Jacques Demy’s bubbly musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is that it is so gleefully and willfully out of touch with the corpus of French New Wave films being released vociferously throughout the 1960s. This is a point of great merit. Compared to, say, Godard’s Breathless, Demy’s Cherbourg is a less cantankerous sort that is less tethered to being violently abusive to cinema. Demy, along with many of the Left Bank directors of the New Wave, was more classicist than someone like Godard to be sure, and he was less drawn to a critique of Hollywood styles. The spirit of defiant rejection of the defiant rejection of the New Wave is very much present and accounted for in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, as loving a tribute to the Hollywood musical as you could hope to find. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: The Leopard

Has there ever been a more luxuriant filmmaker than Luchino Visconti? Probably not, and there was never a more applicable time for a Visconti tornado than in the early ’60s, when cinema all over the world was engorging itself to its breaking point. Of course, by the mid-point of the decade, it would erupt and the entrails would be so gluttonous that no hope of re-patching the beast that was cinema remained. The only chance, really, was to build a new cinema of sorts, and the scabrous knives of the French New Wave, which has been pricking their serrated edges into the balloon of cinema throughout the ’60s to quicken the imminent implosion, was as good a place as any to start. Continue reading

Has there ever been a more luxuriant filmmaker than Luchino Visconti? Probably not, and there was never a more applicable time for a Visconti tornado than in the early ’60s, when cinema all over the world was engorging itself to its breaking point. Of course, by the mid-point of the decade, it would erupt and the entrails would be so gluttonous that no hope of re-patching the beast that was cinema remained. The only chance, really, was to build a new cinema of sorts, and the scabrous knives of the French New Wave, which has been pricking their serrated edges into the balloon of cinema throughout the ’60s to quicken the imminent implosion, was as good a place as any to start. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: The Long Absence

An obvious crux for analyzing European cinema during its proliferation in the 1950s and 1960s is to tether analysis to European cinema’s expression of post-war dislocation and trauma. A critique that is not only fair but unavoidable. I have tended to avoid it in this Cannes series because writing about WWII for every review would get a touch redundant after the first few. Not only that, but context is sometimes a crutch and a shackle in reviewing cinema. Surely, a film like Fellini’s La Dolce Vita or Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel arguably couldn’t have existed without the fallout of the increasingly small world after a steamrolling German blitzkrieg swept across the continent. The war brought disruption to the oppressive order of the old world by forcing the European nations to realize the self-immolating limits of their quest to always expand and rule the world, and such disruption seems instrumental to the trauma essayed in many European films from the time period. Continue reading

An obvious crux for analyzing European cinema during its proliferation in the 1950s and 1960s is to tether analysis to European cinema’s expression of post-war dislocation and trauma. A critique that is not only fair but unavoidable. I have tended to avoid it in this Cannes series because writing about WWII for every review would get a touch redundant after the first few. Not only that, but context is sometimes a crutch and a shackle in reviewing cinema. Surely, a film like Fellini’s La Dolce Vita or Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel arguably couldn’t have existed without the fallout of the increasingly small world after a steamrolling German blitzkrieg swept across the continent. The war brought disruption to the oppressive order of the old world by forcing the European nations to realize the self-immolating limits of their quest to always expand and rule the world, and such disruption seems instrumental to the trauma essayed in many European films from the time period. Continue reading

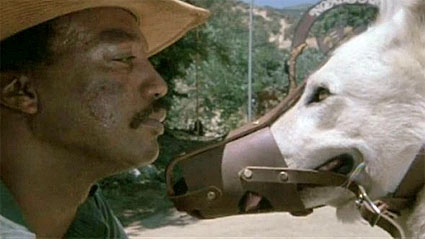

Midnight Screening: White Dog

Two Sam Fuller films this week for Midnight Screenings, one from the very beginning of his career and one from the mature, weary Fuller nearing his end.

Two Sam Fuller films this week for Midnight Screenings, one from the very beginning of his career and one from the mature, weary Fuller nearing his end.

You just want to feel bad for White Dog. No film should be subject to the dogged (excuse the pun) beating Samuel Fuller’s 1982 social expose was, especially coming hot on the heels of the studio absolutely decimating Fuller’s seminal 1980 war picture The Big Red One. Even a worthless production shouldn’t have to wait over a quarter-century to receive any meaningful public exposure after failed preview screenings. No film, I say, should bear this sort of weight. But especially not White Dog, one of the greatest films to even glance at racism head-on. After the film was shunned from theatrical distribution in 1982 and Sam Fuller grew disinterested in making American film productions ever again, its eventual release by Criterion 25 years late is no great consolation prize. Continue reading

Midnight Screening: Pickup on South Street

Two Sam Fuller films this week for Midnight Screenings, one from the very beginning of his career and one from the mature, weary Fuller nearing his end.

Two Sam Fuller films this week for Midnight Screenings, one from the very beginning of his career and one from the mature, weary Fuller nearing his end.

When Pickup on South Street begins, contorted, confrontational eyes are already prowling, lurking, and snapping at one another in a sweatily-packed train. We do not know who is who, and the film relies on that fact, as well as director Samuel Fuller’s acid-tinged eye for the jungle gyms of human collectivity. Scrawled into the film in harsh black-and-white lines by Fuller, a train is an accident waiting to happen, a self-immolating battering ram to the backside of the human ego. There is no community on the train. Just competing interests and faces that almost shout about how they would rather be anywhere else, or anyone else. Continue reading

Review: It’s Such a Beautiful Day

Frankly, modern cinema is a little glazed-over, which isn’t the same thing as saying it is bad. Tons of great films are released every year, but even among the greatest, a certain stagnancy grips them, cuts off their heads, and keeps them grounded. Comedy and animation are arguably the two biggest offenders on this front; when was the last time you can recall a comedy with a legitimate eye for visual framing and using editing and composition to enhance or form the girders of the humor? Films still have interesting stories to tell, but they seldom have an interesting means to tell stories. Content can fly, but the technique, the art of film itself, has been grounded for too long. Continue reading

Frankly, modern cinema is a little glazed-over, which isn’t the same thing as saying it is bad. Tons of great films are released every year, but even among the greatest, a certain stagnancy grips them, cuts off their heads, and keeps them grounded. Comedy and animation are arguably the two biggest offenders on this front; when was the last time you can recall a comedy with a legitimate eye for visual framing and using editing and composition to enhance or form the girders of the humor? Films still have interesting stories to tell, but they seldom have an interesting means to tell stories. Content can fly, but the technique, the art of film itself, has been grounded for too long. Continue reading