It ought not be a surprise that the greatest cinematic study of American iconography, both tangible and nebulous, was unearthed by a German. That film is not Kings of the Road, a sort of slantwise proving ground for greater things to come. It was Paris, Texas, a later film by Wim Wenders and a film whose name evokes the sentimental but bristling irony of a slice of Europe in America. Wenders was that slice, always infatuated with American cinematic styles and moods but trapped in the mortal coil of separation from his ideological homeland, with an unforgiving body of water blocking his way to the land that his heart so clearly desired. Continue reading

It ought not be a surprise that the greatest cinematic study of American iconography, both tangible and nebulous, was unearthed by a German. That film is not Kings of the Road, a sort of slantwise proving ground for greater things to come. It was Paris, Texas, a later film by Wim Wenders and a film whose name evokes the sentimental but bristling irony of a slice of Europe in America. Wenders was that slice, always infatuated with American cinematic styles and moods but trapped in the mortal coil of separation from his ideological homeland, with an unforgiving body of water blocking his way to the land that his heart so clearly desired. Continue reading

Review: Winter Sleep

You don’t feel the seasons in many movies. You don’t feel the grip of the seasons on the humans that would threaten the natural locales that beckon those seasons. You don’t feel the weight of temporal weather and the last forbidding gasp of a season’s tectonic force before it fades away having unleashed the heftiest dying breath it could fathom. You do not feel winter, especially. Frequently, the shorthand for the most temperamental of seasons is a lot of pale white, but we seldom see the nebulous majesty and the tactile dampness of a winter that vacillates between elegant and cruel, often both in the same moment. Continue reading

You don’t feel the seasons in many movies. You don’t feel the grip of the seasons on the humans that would threaten the natural locales that beckon those seasons. You don’t feel the weight of temporal weather and the last forbidding gasp of a season’s tectonic force before it fades away having unleashed the heftiest dying breath it could fathom. You do not feel winter, especially. Frequently, the shorthand for the most temperamental of seasons is a lot of pale white, but we seldom see the nebulous majesty and the tactile dampness of a winter that vacillates between elegant and cruel, often both in the same moment. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: The Mother and the Whore

I have written before that, more than any other cinematic movement, the French New Wave was a line in the sand. If so, Jean Esutache’s The Mother and the Whore is very likely the only film ever to divide up the line, or to redraw it. Not only that, but it draws on the face of the New Wave mythology by casting the mask most commonly associated with the movement – Jean-Pierre Léaud – as a blasé, wandering pseudo-intellectual with an endless pool for inhuman pontification but precious little wells of human warmth. He falls for a nurse named Veronika (Francoise Lebrun), less out of any joy found lurking in her personhood than in a blank need for sex that circles around his personhood like a vulture. He lives with his girlfriend Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who provides the lion’s share of his money, but he plays her as he plays Veronika; as objects and passive beings for him to use as he sees fit. Then, play is a questionable word. That would imply a passion in his heart, but from the beginning of the film until the very end, all we find is timidity and a pregnancy of nothing. Continue reading

I have written before that, more than any other cinematic movement, the French New Wave was a line in the sand. If so, Jean Esutache’s The Mother and the Whore is very likely the only film ever to divide up the line, or to redraw it. Not only that, but it draws on the face of the New Wave mythology by casting the mask most commonly associated with the movement – Jean-Pierre Léaud – as a blasé, wandering pseudo-intellectual with an endless pool for inhuman pontification but precious little wells of human warmth. He falls for a nurse named Veronika (Francoise Lebrun), less out of any joy found lurking in her personhood than in a blank need for sex that circles around his personhood like a vulture. He lives with his girlfriend Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who provides the lion’s share of his money, but he plays her as he plays Veronika; as objects and passive beings for him to use as he sees fit. Then, play is a questionable word. That would imply a passion in his heart, but from the beginning of the film until the very end, all we find is timidity and a pregnancy of nothing. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

Due to ease of access, I’ll be covering 1974 and 1975 before 1973.

Due to ease of access, I’ll be covering 1974 and 1975 before 1973.

Martin Scorsese has returned to the poisoned well of his proving ground far too often. Mean Streets was a vivacious, convulsing snarl of Catholic guilt and post-French Connection inner-city rot. Taxi Driver deepened his fixation on perverting classical Hollywood with a clanking, cantankerous pile of scrap metal as his weapon of choice. Raging Bull perfected all of his pet themes, themes he would relapse to a decade later when things got difficult and he needed a genuine corker of a gangster pic to build up a little good will again. Since then, having earned his cred already, he has too often made the fatal mistake of drinking the water of his own making again and again, and he’s built up a resistance that makes his new films on the same subject seem ironclad in a certain respectable distance and stateliness that devours their energy and liveliness. When he made The Departed, a fine film, he was doing nothing but reheating old leftovers that tasted better thirty years before. The genuine shape and form was still there, but the fascinatingly pungent odors and the sharp acid of the taste was gone. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Thieves Like Us

Due to ease of access, I’ll be covering 1974 and 1975 before 1973.

Robert Altman, bless his soul, has probably done more to review and rekindle American genre cinema than any other American director. He was, in his own less radical but no less effective or warped way, a Godard of the American vernacular, which means both that he released films like he woke up in the morning and that his knowledge of cinema history was prismatic and unencumbered by the mortality of mere humans. Remember, he was older than many of his American New Wave counterparts, and his awareness of the past was more fully grown than even Scorsese’s, a far more famous filmmaker but not necessarily a better one. If you put a gun to my head, Robert Altman would probably be my favorite director at work since the 1970s (Terrence Malick is the only other possibility). Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Solaris

Solaris is many things, but it is most of all the greatest answer film in all of cinematic history. By 1968, Andrei Tarkovsky had already earned the cinema’s eternal respect and humility by debuting as a major world director with the greatest film ever released about the nature of spirituality as it exists in relation to humanity, as it is felt in the senses. He clearly saw the light in Andrei Rublev, but it asked him not to falter or recede, but to continue to preach his gospel. Eying Stanley Kubrick’s eternally cryptic, disquieting, rigidly and pointedly mechanical work of genius, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky plainly grasped the film as a battle cry, as I certainly am not the first to notice. It was Western, for one, and scripturally infested in machines and production, and Tarkovsky was so fundamentally a bleeding-heart humanist that even the early Soviet focus on labor and metal had no use for him, let alone a Western focus on materialism. With 2001 shaking its head at humanity’s ambition and positing a certain greater humanity found in space we could never hope to understand or know, Tarkovsky no doubt refuted the ghostly specter and vast, echoing void of inhuman spaces in Kubrick’s film. Tarkovsky, essentially, felt a calling to bring out the guiding light for humanity once again. Continue reading

Solaris is many things, but it is most of all the greatest answer film in all of cinematic history. By 1968, Andrei Tarkovsky had already earned the cinema’s eternal respect and humility by debuting as a major world director with the greatest film ever released about the nature of spirituality as it exists in relation to humanity, as it is felt in the senses. He clearly saw the light in Andrei Rublev, but it asked him not to falter or recede, but to continue to preach his gospel. Eying Stanley Kubrick’s eternally cryptic, disquieting, rigidly and pointedly mechanical work of genius, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky plainly grasped the film as a battle cry, as I certainly am not the first to notice. It was Western, for one, and scripturally infested in machines and production, and Tarkovsky was so fundamentally a bleeding-heart humanist that even the early Soviet focus on labor and metal had no use for him, let alone a Western focus on materialism. With 2001 shaking its head at humanity’s ambition and positing a certain greater humanity found in space we could never hope to understand or know, Tarkovsky no doubt refuted the ghostly specter and vast, echoing void of inhuman spaces in Kubrick’s film. Tarkovsky, essentially, felt a calling to bring out the guiding light for humanity once again. Continue reading

Un-Cannes-y Valley: Death in Venice

Luchino Visconti sort of had it all, huh? A chameleon by trade, he spent a few decades hop-scotching from proto-Nouvelle Vague Italian Neo-Realism (Rocco and his Brothers) to ghostly melodramas (Senso) to gravid poetic epics with long takes like nitroglycerin by way of molasses (The Leopard) to out and out scorching the Earth with Molotov cocktails of Grand Guignol (The Damned). But his final masterwork was not a picture of succulent opera or intentional, declamatory fire or ice. It was simply a story of an elderly man, played by Dirk Bogard with melancholy sangfroid and still emptiness battling with impenetrable longing in his eyes, and the boy he comes to love while on vacation in Venice. It is an almost wordless work that consists almost exclusively of that man walking around and that boy walking around, and the two sometimes crossing paths with nary a word spoken between them. It is not necessarily Visconti’s best film, but it is his most misread, and possibly for the same reason, his most human. Continue reading

Luchino Visconti sort of had it all, huh? A chameleon by trade, he spent a few decades hop-scotching from proto-Nouvelle Vague Italian Neo-Realism (Rocco and his Brothers) to ghostly melodramas (Senso) to gravid poetic epics with long takes like nitroglycerin by way of molasses (The Leopard) to out and out scorching the Earth with Molotov cocktails of Grand Guignol (The Damned). But his final masterwork was not a picture of succulent opera or intentional, declamatory fire or ice. It was simply a story of an elderly man, played by Dirk Bogard with melancholy sangfroid and still emptiness battling with impenetrable longing in his eyes, and the boy he comes to love while on vacation in Venice. It is an almost wordless work that consists almost exclusively of that man walking around and that boy walking around, and the two sometimes crossing paths with nary a word spoken between them. It is not necessarily Visconti’s best film, but it is his most misread, and possibly for the same reason, his most human. Continue reading

Midnight Screening: Edward Scissorhands

And another Midnight Screening, because I had it prepared this week anyway, and because it celebrates the 25th anniversary of a personal favorite.

And another Midnight Screening, because I had it prepared this week anyway, and because it celebrates the 25th anniversary of a personal favorite.

Once upon a time, Tim Burton loved cinema. He loved everything that cinema had been and everything it could be, thus his penchant for reworking cinema’s history into warmly inviting, devilishly cunning new wholes. It is also why he fell for characters who, in one way or another, resembled himself. In his masterpiece, Ed Wood, it was the titular character – a warped conjurer of perverse kitsch and American lore – who Burton no doubt saw in himself. In Edward Scissorhands, though, Burton’s proxy isn’t the titular character, but the gentle old inventor, played with loss in his eyes by Vincent Price, finding an avuncular warmth struggling to survive the cryptic winter of the life of an outcast inventor known only to his creations. His life is an attempt to meld a friend for himself, a gentle, sweet variation on the mad genius myth of so many horror films long past, and a tacit reflection of Burton’s undying sympathy for his material. Continue reading

Midnight Screaming: The Hills Have Eyes

It is with a heavy heart that I post this Midnight Screening on the occasion of horror maestro and professional boogeyman Wes Craven’s untimely demise. But what better way to honor his legacy than with a review of his best film?

It is with a heavy heart that I post this Midnight Screening on the occasion of horror maestro and professional boogeyman Wes Craven’s untimely demise. But what better way to honor his legacy than with a review of his best film?

Once upon a time, Wes Craven was a wandering journeyman horror director of the micro-budgeted exploitation cinema school, wielding a fancy for American genre cinema and European art-house works (his debut remains cinema’s most demented Bergman remake, after all). He spent five years struggling up the funds to direct his second feature, 1977’s The Hills Have Eyes, after unleashing one of the most controversial features of the modern era in 1972: The Last House on the Left. As important as that film is, however, The Hills Have Eyes is a superior effort in every way. More impeccably crafted yet more divorced from the respectable doldrums of “prestige” that craft often carries with it, Hills is the Wes Craven film that feels most like tetanus. Continue reading

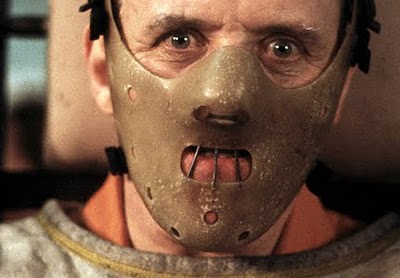

Progenitors: The Silence of the Lambs

What with all the hullabaloo around the televised Hannibal struggling to survive, let us turn our attention to the grand opus of the character and, with all apologies to Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the primary cause of the character’s continued social relevance today.

What with all the hullabaloo around the televised Hannibal struggling to survive, let us turn our attention to the grand opus of the character and, with all apologies to Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the primary cause of the character’s continued social relevance today.

It’s not that good, but it’s pretty good, as they say.

Jonathan Demme’s baroque 1991 exercise in rekindling the exploitation fire that stoked his loins twenty years before is something of a coming home party. Remember, this man’s first directed feature was a tried-and-true “women in prison” film, arguably the most exploitative of all exploitation sub-genres, and in the intervening years, the greatest concert film of all time notwithstanding, Demme largely retreated to the more stable, less satisfying regions of “respectable cinema” for middle-aged suburban couples, a state he has since, unfortunately, returned to. It is no surprise that The Silence of the Lambs boasts an undeniable passion of craft, right from the misty, positively soaking wet autumnal forest it begins in all the way to the audience-implicating, voyeuristic conclusion. Demme’s heart is in it, and his heart was in it so much that he managed to have it both ways and tally up a few Oscars (a lot of Oscars) and a tidy paycheck or two. The Hollywood machine is a shame, but sometimes, and only sometimes, it gets it just right. Continue reading