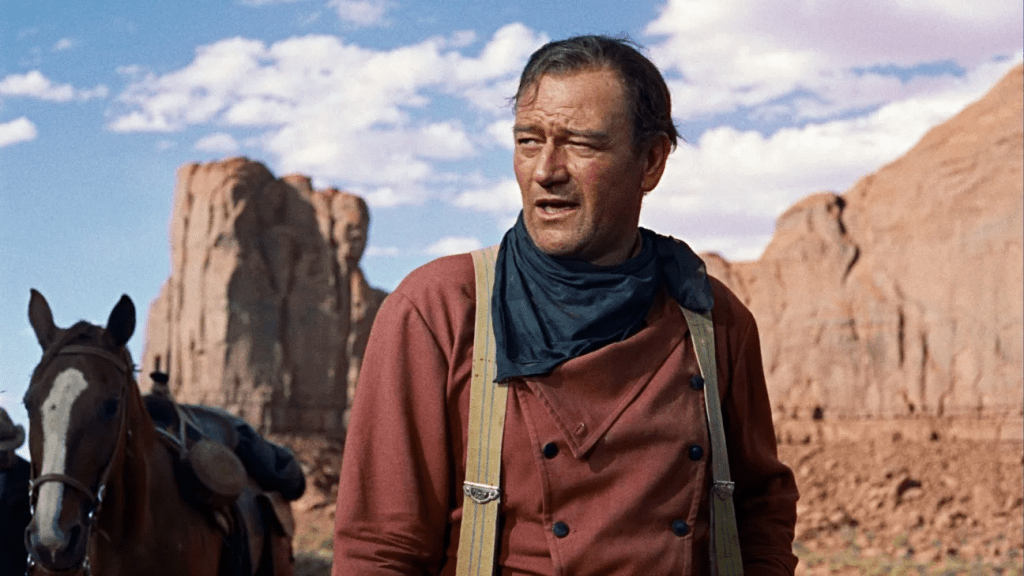

While the received wisdom about the Western genre presents it as an assured space of spiritual solitude or a canvas for self-betterment through restorative strenuousness, you’d be hard-pressed to find a Western more worried about its own beliefs than John Ford’s The Searchers. The only thing really working against the film is how thoroughly its reputation precedes it. Its self-critical nervousness has paradoxically been suppressed and composed over decades into a vision of the solemn, self-assured object imperially judging its forebears. This is a supposed masterfulness that the film itself may not need, nor ask for. But, of course, that is the difficulty, and the paradox, of John Ford. The Searchers is entirely aware of the cultural baggage it carries. Far more than era-concurrent works like Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73, it self-consciously courts, and creates, the mythopoetics of the frontier space as a moral battleground – rather than Mann’s amoral void – on which the fate of the proverbial nation is to be staked. Its screenplay by Frank S. Nugent, based on the novel of the same name by Alan Le May, is transparently freighted with the heavenly wisdom of the noble stranger archetype, the paradigmatic American: isolated in their heroic, if tragic, dignity while being able to fluidly move into and out of various social milieus without being “of them.” This is a film that seems to have recognized how important it was before it was released, something that usually spells death for a living, breathing work of art. Yet rather than solidifying itself into a work of serene self-criticism, the interesting thing about Ford’s film is how worried it seems to be that it hasn’t actually figured out what to say about the genre laid out before it. The genre, in Ford’s vision, is not a passive resource to be either churned into self-conscious mastery nor to be dismissed or depleted into a ruse, which of course would only be another way for the film to celebrate its own assurance that the genre was morally repugnant. The West, in The Searchers, is neither a landscape to excoriate nor to celebrate. It is a vast store of uncertainty, a wellspring of consternation.

That doesn’t mean The Searchers doesn’t court the favor of its genre. The film’s interest, unlike so many heroes of the classic West, is that it transparently can’t escape its history, which means it must draw on the very mythos it can’t figure out. Wayne’s Edwards, the Western wanderer, is clearly the most capable man in the film, but he is also the most dangerous. He remains the film’s icon figure, like any good Western, but he is also the vortex around which the film distorts itself and the precipice it must confront but cannot fully peer into. While Wayne’s famous character introduction in 1939’s Stagecoach projects an imposing, all-consuming monolith overcoming a figurative landscape which he himself apexes and dwarfs, here he enters the film strolling in from a landscape that still seems to consume him, into a door that cannot fully protect him. While Stagecoach literally enacts the triumph of human over landscape in that moment of charged, almost phallic agency, The Searchers is a world in which humans seem essentially trapped in a tide of violence and vengeance that defrays the teleological, progressive structure that Manifest Destiny was predicated on. This is a not a man erected as a savior and defiler of a material, almost anthropomorphized abundance, but a lonely fellow who has come in from the cold, only to find that he imperils the very domesticity that he claims to protect.

Continue reading