Rosewood’s most salient character is a figure who seems to recognize that he has walked into Rosewood out of an entirely different film and that he wears a century of American cinematic lore on his back. He is a cowboy, a disciple of the wandering lifestyle that has its roots in the nebulous core of American life. He is an opaque drifter as archetypal as Shane or The Man with no Name or McCabe. Indeed, he isn’t even a man with no name. He is named Mann (Ving Rhames), a self-consciously iconographic masculine drifter who wears his self-composure and cultivated distance from history on his sleeve. His icy competence, ably displayed throughout the film, is tethered to his dispassionate reserve, his displacement from the forces of history that have shaped him and his aspiration to act as though he is beyond those forces even as he fully embodies an icon that itself constellates and coagulates the forces of American lore. He can help save the town of Rosewood, an African American oasis in the middle of Jim Crow Florida that he wanders into, for the same reason that he doesn’t want to. He has seen history weighted against his, and their, Blackness, and he has decided to abscond from history. Rosewood is the story of that man recognizing his own complicity with those historical forces. It is his attempt to redirect them in an insurgent, counter-historical assault.

This film’s obvious interest in Mann’s predicament, and its concern about that interest, is felt in every frame, not only because it is the film’s story but because it is its ontology, which is to say, its own being. That’s because Mann is also a cipher for writer-director John Singleton’s own combative, conflictual relationship to the Hollywood machine, to a force he both wants to claim as his and a fear that it neither wants him nor he it. In hoping to wrangle forces of history and structures around him like an itinerant, independent maverick, a man who is inside and outside the world, he weaponizes the forces of his oppression against them. Just as Mann tries to embody the American cowboy figure against itself and emerges unsure about its final value, Singleton plunders the American picture-book both to invest in the cultural markers of resistant Americanism and to imply that they may not actually be worth saving.

Singleton’s neo-Western style, reinterpreted and strip-mined for a radical poetics, finds a cipher in Mann, an ex-soldier who, like many other African Americans after the Great War, aspired to “close ranks” with white Americans, a showcase of American piety that quickly became a reckoning with the limits of sacrifice. For many returning African Americans, an aspirational hope of national togetherness quickly exposed feelings that their faith had been misplaced. Displays of support for the American spirit, they realized, had severe limits as a basis for a progressive politics or the facilitation of a joint racial venture of national development.

The war, then, was also a frontier of a kind, a space in which many African Americans reported experiencing the loosening of social structures and the inherited assumptions from their life in the U.S., seeing equal treatment for people of multiple races for the first time not in the U.S. armed forces, which were segregated, but in European society. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that African Americans “returned from fighting” and they “returned fighting,” and the renewed vigor to fight oppression felt by many African Americans reflected a sensibility girded against forces of oppression at home and abroad.

Mann begins the film reflecting this ambivalence. He is certainly unqualified in his agency. He has no qualms about displaying his frustration with racism. But his solution is a retreat into a decidedly individual life, a turn to a world apart, one within the confines of himself. His frontier horizon is not to change the system, but to escape it. Yet Rosewood, the town he discovers, is also a frontier in another sense. Rather than easing us into the acceptable pathways of liberal American multiculturalism, as most Hollywood history films of its vintage did (and still do), Rosewood makes a claim on a region of Black history outside the harmonies of what Gunnar Myrdal called the “American creed.” The African American town of Rosewood is one in which the Black residents have fashioned a collective rejection of America. They’ve accepted the Faustian bargain of segregation as a slantwise path to possibility, if not progress.

Indeed, Rosewood travels in one of history’s forgotten trenches here, an unexpected, seemingly oxymoronic frontier not in the Wild West but in the Deep South, where the seeming fixity and entrenchment of history can belie odd occurrences and improbable freedoms born out of the trickster god that is history, a space in which people do not act according to code. It was in the backwoods of Florida that the first independent Black town in what would be the U.S. was founded near St. Augustine, when the area was still controlled by the Spanish. It was in Florida where Mary McLeod Bethune led an African American school for girls. Authors like Zora Neale Hurston would go on to parlay their life within modern independent Black communities in the South (Florida, in her case, as well) into inspired cultural commentary on the beauty and complexity of communal Blackness uncoupled from any claims on white society. The independent African American town of Rosewood, much like Mann’s recalcitrant refusal, suggests a renewed commitment not to invest all of one’s faith in the gradual evolution of American civic-national opportunity. Instead, the people of Rosewood look to make freedom and progress on their own terms, not by kindling with America’s hopes but by tracing America’s shadows. Focusing on their own space, the people of Rosewood suggest, might actually attack discrimination from a different front, wielding the admittedly back-stabbing weapon of segregation in a way that carves out some opportunity, however dubious, within it.

As with Mann’s masculine individualism and Singleton’s Hollywood filmmaking, this path is also an attempt to wield structures of inequality as best they could, to survive and work with the devil, to hold one’s own in the belly of the beast. History has been ambivalent about these paths, as, importantly, have Black radicals, many of whom, even in the 1920s and 1930s, felt that interracial class-based solidarity was the only viable way to pursue real, lasting change in a world of increasingly interconnected capital. A Black town would never escape the structures of racial inequality. It could only, much like Mann’s projected vision of cowboy charisma, hold them at bay.

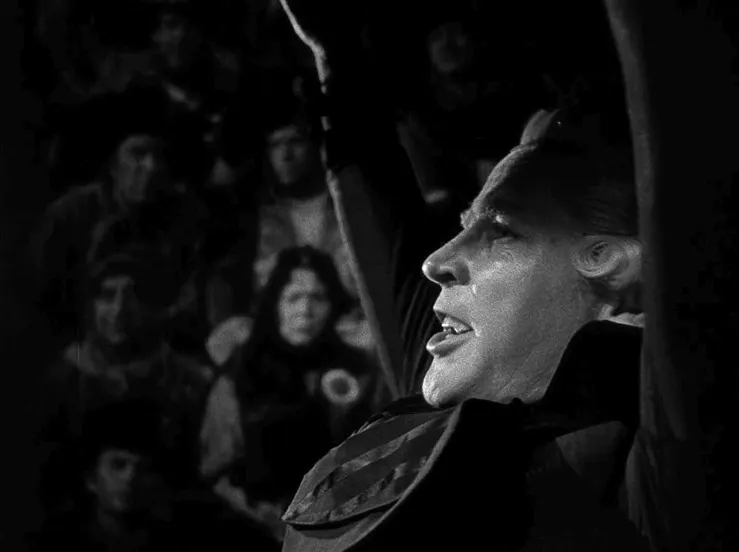

Rosewood recognizes this problem. While it is distinctly a film about a Black community’s hard-won, albeit incomplete, security, Singleton’s text is also unusually attentive to the dynamics of white attitudes toward Jim Crow, attitudes that inevitably limit the possibilities afforded the Black characters when a lie stokes the simmering racial tensions into a full-blown holocaust. When the white residents of a nearby town run riot over the residents of Rosewood, raising it to the ground, they show little remorse for their actions. Those who did, Rosewood suggests, may be no better. In a grave, gravitational shot, one that seems at once to center the film, to hold it close to the ground, and to force it to confront its demons, Sheriff Walker (Michael Rooker), who has been nominally trying to hold the white mob at bay, raises up in the foreground, center-frame, suddenly blocking the massacre’s first black body being hung directly behind him. This isn’t the film’s plea to empathize with this white man, a wounded expression of the white man’s soul asserting moral and epistemic precedence over the Black man’s body. The film will not shy away from raw confrontation with the desecration of Black flesh throughout, but, in this image, the point is precisely that this white man’s feelings of guilt are taking up time and literal screen space over the actual story of the dead Black person. Walker constantly adopts a masquerade of unearned beneficence in the interest of making the story about him rather than acknowledging the grotesque brutality he has condoned and legitimized. He looks forward in the frame, apparently certain yet actually lost amidst the contradictions of history he wants to have move forward and stand still, whereas someone like Mann effaces himself and relies on reticence and ambivalence to radiate a quiet dignity and, when need be, a brutal charisma. It is Walker who cannot see the myopia of his missionary self-image, and the limits of his self-aggrandizing brand of brittle liberalism, not Singleton. He is, as it were, an allegory for a white Hollywood happy to array itself against white racism when it is played with a country accent and knotted into a rope but not when it is wielded by apparently more enlightened forces.

Singleton’s investment in and ambivalence about Hollywood cinema is apparent in nearly every frame of Rosewood, a film that sees him shun the position of a fervent acolyte of cultural inclusion to become, instead, an armored interpreter of America’s worth. He adopts the position of a volatile vagabond moving through Hollywood’s trenches, a renegade man wrestling with his own inner frustration, perhaps his own inner complicity, and turning those aspects of himself against the system that condones them. His film doesn’t fully escape this system. But that’s the point. This is tenuous stuff for a provisional history. Rosewood imagines no inexorable march of progress. It doesn’t lead us, Moses-like, into a better world. It submerges us into a conflictual netherworld in which the forces at play in the world are never stabilized, in which the niceties of civilizational advance are always potentially surface level masquerades for churning material tensions that have to be constantly maintained by implicit threats and by the possibility of more overt forms of violence.

Ever attentive to these knots of history, Singleton does exquisite compositional work throughout. His multi-sided, prismatic frames situate humans with and against each other, their surroundings, and the wider world. Unexpected truths are clarified to our eyes that are only dimly apparent to the characters themselves. Late in the film, for instance, John Wright (Jon Voight), a liberal white store owners and one of the few white residents of Rosewood, walks back home to his house, perhaps the only building left standing in town, when the camera attunes us, but not him, to the body of his Nlack employee in the foreground. She lies dead in the road because she couldn’t bear the thought of being harbored by the man who, although seemingly caring, nonetheless showed little compunction about asserting himself onto her sexually earlier.

The shot inverts the image of the sheriff rising above the dying black man. Here, an ambivalent, if finally more heroic, white man recedes into the distance, perhaps to a renewed conviction or perhaps to an unchanged moral compass, as the camera moves us to the position of displacing him with the body of a dead Black women who he has, metaphorically, turned his back on. This is a vastly more frustrated, frustrating, hesitant portrait of white liberalism than another Hollywood film, with its self-serving, artificially redemptive aura, would have managed. Wright is an essentially permissive man, open to the structures of liberal modernity, but he is also a capitalist who obviously feels good about himself for exhibiting a more enlightened disposition to the Black residents of the town. He is a vision of Janus-faced white American modernity, embodied most clearly in the film’s final climax, where he boards a confiscated train, a symbol of modernity, to Jacksonville, while the two Black men who are the film’s other heroes ride off together on horses, unable to participate in this story of modern progress and unwilling to forget the violence it was built on.

When Mann and Wright salute at the end of Rosewood, having worked together to save the Black children of the town, the film doesn’t necessarily understand this as a moment of commiserative honor. Their ex-military camaraderie, consummated in a shared salute, is as much a display of their confusion about their own commitment to any cause other than their own survival throughout the film. These are the two most liminal men in the film, neither with or apart from the Black town. Mann, for his part, has finally decided where he stands. Wright, conversely, seems to want to sit on the fence. He is a man who is theoretically likely to go back to his own ways, who disowns abject violence but is also accepting of structures of oppression insofar as it suits him. Rosewood is fully aware that his participation in the heroism of the climax may be pyrrhic, that Wright may go back to his old life, whereas Mann and Rosewood resident Sylvester (Don Cheadle) seem to be riding through a nation that has no safe place prepared for them.

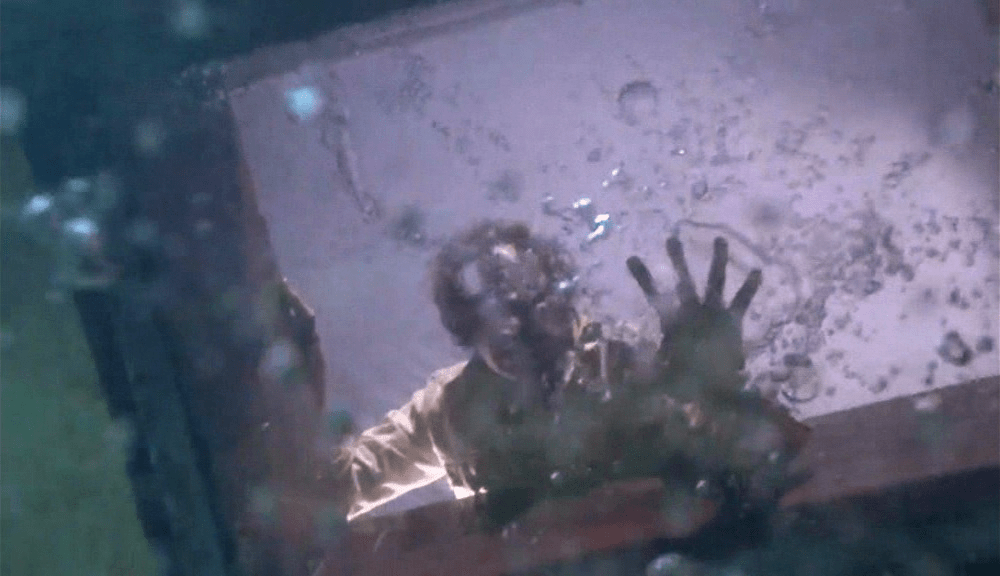

It is Sylvester, then, who exhibits the film’s other revealing arc, the one which forces him neither to recognize his participation in a hopeful community nor to reckon with his complicity with an oppressive one but to acknowledge the decimation of his community and apprehend its continuance, albeit in a new form. A member of Rosewood, Sylvester is an embodiment of the educated Black landowning class who is emboldened and hesitant, who knows how to wield a veiled threat and stand up for his rights and to demur and mask his indiscretion without fully denying it. He is, with a piano or a gun, good with his hands. Yet he can only survive the film by hiding in his mother’s casket at a pivotal moment. He is nearly buried with the remains of the woman who reared him, played by Esther Rolle, whose most famous role, matriarch of a compassionate, fragile Black family for the modern urban world, reared many youths on intra-relationships in the Black community and the liminality of freedom even in the “progressive” North.That character, of course, was named Florida, an echo of the Black Southern past still alive in the North. Sylvester’s return at the end of the film is a metaphorical rebirth born out of a closeness to death, a near-demise that hammers a new man out of the currents of historical oppression and human agency. His is a life through which Singleton weighs the competing urges of staying and going, resisting and demurring, holding onto the possibilities etched out of an oppressive past and locating a new future.

With a fire and brimstone cinematic charge, Singleton creates a historical double-sided sword that exhumes the hellish currents of Jim Crow segregation as a lamentable, damned land that nonetheless radiates collective humane warmth and possibility forged in spite of the structures around it. While Mann has to relearn what it means to connect to a history and a community, Sylvester transmutes his inheritance into a new creation, not as something to myopically hold onto and curate but as material out of which something living might be created. This is perhaps Singleton’s vision for himself, as an interpreter of classic Hollywood luster and a griot harnessing cinema’s potential for coaxing out the collective, compositional relations tying humans and structures. He weaponizes the history of people in place, living and dying in a horrible world, bearing witness to an imperfect existence as they act with the feel for a better one insurgently pushing its way into the grime of the now.

Score: 8.5/10