Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice.

Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice.

This introductory image of the fire next time, both demonstrative and agnostic, willing to declare solutions with moral conviction and then pessimistically pockmark this conviction with shades of doubt, potently evokes the spirit of a filmmaker who has a certain feverish commitment to the belief that Hollywood style is a viable idiom for African-American stories – that the tools and tricks of old-school melodrama and cliche can be nervously renewed – and that these convictions must be interrogated. Like so many classical Hollywood films, Singleton’s vision is brashly direct in its viewpoints, but its confident forward stride belies a real shiver of hesitation. Not only a suspicion of its own decisions, mind you, but a mistrust of anyone’s ability to answer the fatalistic quandary – the choice between retaliatory violence and ostensible, possibly ephemeral peace – that genuinely emanates from the souls of these characters, a decision which we are all hopelessly unqualified to make.

Particularly telling is the way Furious Style’s sermon-esque pronouncements about institutional racism, with their flair for the didactic, suggest a personal anxiety about his son’s future which is nonetheless beholden to certain stuffy markers of respectability politics which the film, ultimately, can’t but query and reconsider as it goes along. It engages the supposedly faultless morality of mainstream society, with its presumably clear-sighted attitude toward rejecting violence, by considering the severity of ground-level conditions which perhaps preclude such ethical guarantees, all without dismissing the consequences of the actions perpetrated by the characters within.

Or without forgetting those characters. Where Ice Cube’s Doughboy becomes the ultimate moral avatar of the Faustian bargains made for success, or even survival, in the hood, there’s no sense that this is a screenwriter’s contrivance, or a hand-wringing moral imposition. Rather, it takes the form of a poetic evocation of the tragic inevitability of life on the streets, a sense of grim permanence that implies not the nihilistic denouncement of any possibility of change but the frightening cyclicality of a recurring nightmare. One that, perhaps, the characters could still hopefully wake up from. In the film’s artistic zenith, much more troubling than Ricky’s famous, melodramatic demise, his brother Doughboy suffers a final, vaporous disintegration, a ghostly reminder that some forms of escape go unvisualized, maybe cannot be visualized, in and by a film that nonetheless strives to materialize the potentially unimaginable dream of a fuller life.

Original Review:

With the release of Straight Outta Compton taking the world by storm, let us turn back the clock to a cinematic statement of urban life featuring the initial breakout star of the musical crew.

Occasionally, there are seismic shifts in the Hollywood landscape. The early ’90s influx of films made by and focused on African Americans doesn’t exactly fit the bill (it was cleansed from production schedules almost before it began, but vestiges retain, and a rebirth over the past few years, befitting the mid-2010s nostalgia for early ’90s culture, is still on the rise). For a while though, Spike Lee, John Singleton, and a few other African American filmmakers were unleashing some of the most vicious cinematic dogs upon society that America had seen in quite a while. The early ’90s were not happy times for Americans, and the recession brought forth increased public awareness of inner city poverty. With it, Hollywood wanted to do as it does and shed a little light on such problems in a way that ’80s cinema had uniformly overlooked. Continue reading →

With Spike Lee’s temperamental Chi-Raq finally unleashed upon us, let us turn to Lee’s last unambiguously popular film, a work that has now largely been forgotten and lamented with cries of “selling out”.

With Spike Lee’s temperamental Chi-Raq finally unleashed upon us, let us turn to Lee’s last unambiguously popular film, a work that has now largely been forgotten and lamented with cries of “selling out”.

What with Ash vs. Evil Dead trouncing the television world, a review of the film that started it all is in order…

What with Ash vs. Evil Dead trouncing the television world, a review of the film that started it all is in order… With Steven Spielberg at war again with Bridge of Spies, let us return to arguably his most famous war film.

With Steven Spielberg at war again with Bridge of Spies, let us return to arguably his most famous war film.  As there are reports of the Muppets on television for the first time in a few decades, a review of the first incursion of the Muppets into cinema was in order…

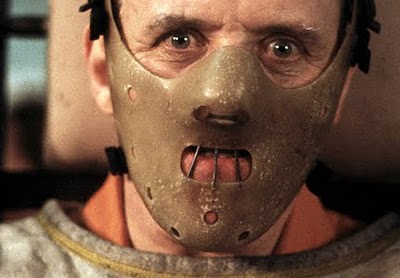

As there are reports of the Muppets on television for the first time in a few decades, a review of the first incursion of the Muppets into cinema was in order… What with all the hullabaloo around the televised Hannibal struggling to survive, let us turn our attention to the grand opus of the character and, with all apologies to Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the primary cause of the character’s continued social relevance today.

What with all the hullabaloo around the televised Hannibal struggling to survive, let us turn our attention to the grand opus of the character and, with all apologies to Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the primary cause of the character’s continued social relevance today. Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice.

Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice. Directed by David Wain and written by Wain and Michael Showalter, 2001’s Wet Hot American Summer is one of the few legitimate “cult classics” to have emerged post-2000. Sure, we’re always discovering new “old” films from the gutters and cemeteries of cinema history, some via revelatory re-releases or the increasingly miniscule parade of independent theaters pining for midnight screening success to fight the corporate behemoths of Big Theater. But a modern film that has emerged as a cult classic? Now that is a rarity, largely because most of the modern films we identify as cult classics don’t meaningfully fit the term. People can introduce the likes of Anchorman and The Big Lebowski within the halls of “cult classics” all they want, but that doesn’t change the obvious box office success of both films relative to their budgets. Calling them “cult” films only applies if “seemingly all Americans between the ages of 18 and 35” meaningfully qualifies as a “cult”.

Directed by David Wain and written by Wain and Michael Showalter, 2001’s Wet Hot American Summer is one of the few legitimate “cult classics” to have emerged post-2000. Sure, we’re always discovering new “old” films from the gutters and cemeteries of cinema history, some via revelatory re-releases or the increasingly miniscule parade of independent theaters pining for midnight screening success to fight the corporate behemoths of Big Theater. But a modern film that has emerged as a cult classic? Now that is a rarity, largely because most of the modern films we identify as cult classics don’t meaningfully fit the term. People can introduce the likes of Anchorman and The Big Lebowski within the halls of “cult classics” all they want, but that doesn’t change the obvious box office success of both films relative to their budgets. Calling them “cult” films only applies if “seemingly all Americans between the ages of 18 and 35” meaningfully qualifies as a “cult”.  Frankly, modern cinema is a little glazed-over, which isn’t the same thing as saying it is bad. Tons of great films are released every year, but even among the greatest, a certain stagnancy grips them, cuts off their heads, and keeps them grounded. Comedy and animation are arguably the two biggest offenders on this front; when was the last time you can recall a comedy with a legitimate eye for visual framing and using editing and composition to enhance or form the girders of the humor? Films still have interesting stories to tell, but they seldom have an interesting means to tell stories. Content can fly, but the technique, the art of film itself, has been grounded for too long.

Frankly, modern cinema is a little glazed-over, which isn’t the same thing as saying it is bad. Tons of great films are released every year, but even among the greatest, a certain stagnancy grips them, cuts off their heads, and keeps them grounded. Comedy and animation are arguably the two biggest offenders on this front; when was the last time you can recall a comedy with a legitimate eye for visual framing and using editing and composition to enhance or form the girders of the humor? Films still have interesting stories to tell, but they seldom have an interesting means to tell stories. Content can fly, but the technique, the art of film itself, has been grounded for too long.  Vacation was the first zeitgeist-defining hit for a young John Hughes, writer for National Lampoon and eventual savior of its brand name, albeit only temporarily. Hughes, who would go on to direct his fair share of generally more teen-focused films that tend to fall into the quintessential and unmatched “basically solid and fine but primarily unexceptional and more notable for not being the schlock coming out on either side of them” basket from the mid-to-late 1980s. Hughes wasn’t the funniest writer, or the most precise, but he had an unbridled warmth and generosity about him that melded with his legitimately caustic ear for everyday human experiences, a bond that ultimately allowed him to create his fair share of sentimental, humanistic films that sometimes veered into sickly sweet, but generally stayed on the right side of the line.

Vacation was the first zeitgeist-defining hit for a young John Hughes, writer for National Lampoon and eventual savior of its brand name, albeit only temporarily. Hughes, who would go on to direct his fair share of generally more teen-focused films that tend to fall into the quintessential and unmatched “basically solid and fine but primarily unexceptional and more notable for not being the schlock coming out on either side of them” basket from the mid-to-late 1980s. Hughes wasn’t the funniest writer, or the most precise, but he had an unbridled warmth and generosity about him that melded with his legitimately caustic ear for everyday human experiences, a bond that ultimately allowed him to create his fair share of sentimental, humanistic films that sometimes veered into sickly sweet, but generally stayed on the right side of the line.