When they created Hangover Square, star Laird Creiger and director John Brahm had already collaborated on an American remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s silent classic The Lodger. That foggy cobblestone of a picture was as close as English language silent cinema ever got to the shadowy sublimity of German Expressionism, and the remake was a malevolent Hollywood horror-noir about European violence for a nation currently embroiled in the international contradictions of Western democracy. This follow-up, however, is even more capable of limning the thin line between the heavenly and the demonic, between modernity’s potential and its conundrums.

Adapted by Barré Lyndon from Patrick Hamilton’s popular 1941 novel of the same name, Hangover Square depicts progress’s gloomy underbelly in the story of a creator harboring a dark secret he isn’t even aware of, an inner shadow he cannot stabilize. For Laird Creiger, the man playing the tortured creative entity, it no doubt resonated with his desire for social acceptance, to be a hero in a world that had typecast him as a villain. By the time the film saw its release into the world, Creiger would be gone from it, dead from a self-imposed crash diet, including amphetamine use, the result of a rampant desire to be a leading man. By the end of this film, his character George Harvey Bone will likewise immolate himself in the poetry he pursued, releasing himself into a tragic uncertainty that he could not resolve in his life and which finds luminous resonance in his art.

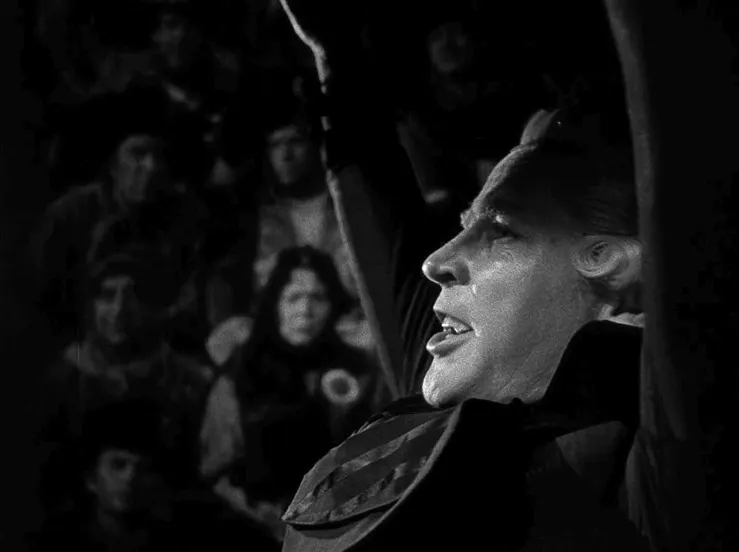

Creiger’s sudden demise, and the shatteringly nervous performance he delivers in a character that clearly channels his inner ocean of frustration, is probably the reason why Hangover Square lingers in the shadowy recesses of the public memory. But this magnificent phantom of a film is an unquiet mind in which George’s artistic confusion doubles for Creiger’s own appetite and his socially unallowable sexuality (rumors abounded, and constructed relationships were displayed in public to present him as a heterosexual face for a movie poster). His portrayal of Bone is deeply moving and frightening, a vicious caricature of a society that produces compromised selves and displays its violence onto the souls of the unwanted and the otherized. One of his lovers warns him not to be “so far away.” Elsewhere, she asks him if he is “with me or with somebody else?” But Creiger seems to not be with himself, to be at odds with his own body, deranged by a world that quickly moved him from the fringes to the center but which didn’t, finally, have a place for him.

His Bone is an aspiring, brilliant composer in Victorian London who suffers from sudden eruptions of confusion and piercing episodes of uncertainty. When one of them leads to fugue state on the same night as a murder occurs near his flat he and his fiancé Barbara Chapmen (Faye Marlowe) confront Dr. Allan Middleton (George Sanders), who assuages him but quietly harbors suspicion. We need no suspicion because we’ve seen him commit the act in the film’s misty opening which, via the lighting of a streetlamp and a track inward from the streets to a private domicile, announces its illumination of the hidden reservoirs of brutality beneath the modern world. But he genuinely cannot remember the act, and he had no intention of doing it. This inverse Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, who is not trying to unleash his inner primordial id but who is trying very desperately to keep it at bay because he seems unable to, presents a decidedly sympathetic mirror of the early 20th century’s vision of itself. Within this violence, Bone finds a kind of dark power that is also a lapse into nothingness, a trancelike agency that is also an unmaking of self.

This is a fractured man, a huge behemoth who was also a shivering mouse. His character is a deeply ambivalent protagonist, almost frighteningly undecidable. At one point, when this towering beast of a man walks toward the screen, the camera seems to cower in fear, as though he is pushing the screen toward him and it is running away at once. A later image suggests the subtlest outline of his coat and hat in the background with his umbrella handle looking like a knife stuck through the coat’s chest, a symbol for the death of self creeping around the background of his life that he is unable to directly acknowledge and confront. When he opens a pocket-knife in front of his face, he wields a weapon of selfhood that is also figured as a schism of the soul.

On-screen, Creiger finds an odd sort of power in harnessing his unacknowledged impulses, in unleashing his otherness onto the camera. When his other lover, singer and burlesque dancer Netta Longdon (Linda Darnell), who is transparently using him to advance her career, envelops him, the camera pulls in to the two of them, suffusing the material background in a black void. Absent the exterior world, the darkness consumes them in an absolute emptiness in the vehicle, a passage to a desire he cannot admit but which encloses him in a narcotic nonetheless. In the back-half of the film, he begins to accept himself as the beast that society made Creiger himself to be.

If this positions Creiger only as a doomed other who falls prey to his own monstrousness, Hangover Square also presents Bone’s tormented “black little moods” as cracks that open the world around him, that gouge out a vision of the social abyss pressing itself upon him. The city streets are pock-marked with ditches one might fall into, indicators of a modern London violently etching its way into the world, forcibly being made and unmade repeatedly. Fire torches, through graphic matches, become gas lamp lights, implying a modernity that is only ever a tightrope between a cavern of unmaking and a void of violent possibility. When George kills a victim off-screen, a bicyclist tragically runs over his cat, a kind of psychic tremor transported by his sensitive soul through the caverns beneath the city being dug for the subway system, as though London and everyone in it is tied together with a garrote of their own nerve endings.

This tension, not unlike the cord George wields like he’s tying his necktie, becomes truly vertiginous in the film’s harried, apocalyptic depiction of a Guy Fawkes Night party. Brahm and cinematographer Joseph LaShelle figure a celebration of national unity as a deranged homogeneity, a mountain of fake bodies all-too-easily crowned by a hidden real corpse all too easily masked as another effigy. Nationalism’s hidden brutality, here, is publicly acceptable, and yet still finally masked. Bone easily anoints himself the apex of a bonfire of collective chaos, not as its shunned outside but its repressed inner instability.

Of course, that’s being too cohesive for the film’s sensibility, and perhaps too radical. To read a film as restless and feverish as this one may be a fool’s errand, or it may suggest a text that was simply confused about what it was trying to say, or it may suggest that good art is, like Bone, tortured by its irresolution, by a drive for composure and Apollonian form entangled with an unraveling impulse to engage Dionysian force. The film is neurotic, and so were the people who made it. Creiger, of course, no doubt wouldn’t connect his own internal frustrations with this man’s murderous energy in any one-to-one way, but the point is society might have, an uncomfortable fit that allows the film to work multiple angles of social discord. Indeed, his two supposed lovers – although both relationships are notably, suggestively chaste – are clearly marked and opposed as arbiters of light and darkness, classical virtue and modernist force, yet they are often paired and echoed in various shots. This all may indicate that the film doesn’t hold up to a sophisticated and choker-tight reading, but that it prefers to run rampant, even to corrupt its own self-interpretation, and that the text is, like Bone, too uncanny and too bruised to do much other than unleash itself upon a world that has confused it.

Indeed, the film self-consciously rejects any stable reading of its drama. In one moment, we see Bone from behind, his face visible in a tiny mirror, and we sense that Bone can only see a miniaturized yet aggrandized version of himself, both smaller and bigger than he really is. The film won’t finally settle on the right way to view him, so instead it discharges him upon the world in a conflagration of a final performance in which the maddened Bone combines pieces written for both women into a swirling vortex of ravishing light and swooning darkness. His hands play fiercely and restlessly, not quite the unthinkingly violent automatons from the 1920s WWI, where the pianist’s hands were often figured in German horror as uncontrollable, runaway machines at odds with the reasonable, thinking mind. There, we get the sense that the misbehaving parts could be extracted, that inner cohesion and its capacity to produce and temper creative form could find he right balance between mechanization and human soul. Here, instead, the hands mark the artist as a savage, sublimated portal finally unloosed in an ecstatic blossoming of personal serenity and self-destructive turmoil, a man entirely in control of his own dialectical and dialogic exasperation and conjuring it in a tempestuous release of sheer energy. In this view, the artist harnesses the world’s buzzing natural chaos and complexity, scouring the shadows for signs of a dark and nebulous otherworld and hoping to stay in the penumbra, somewhere in between announcing social unrest and succumbing to complete malevolence, hovering between dark and light.

Bone, in this sense, is the tortured chronicler of a nation unsure of what composure means in the ascendant 20th century. His fits of rage are set off by loud, discordant noises, by the shocks of city life that interrupt the surface-level harmonies of the mind and of reality itself. At one point, he is disturbed by metal tubes falling of a transportation cart, by the scaffolding of technological modernity itself. They look uncannily like Luigi Russolo’s famous tube-like instruments invented to capture and channel the democratic polyphony of a frayed modern urban landscape, what at least one scholar has called the “emancipation of dissonance.” Russolo promised a new sound, a conduit for the discordant polyphony of a modern landscape, and his effervescent, corruptible vision of the 20th century would both climax in revolutionary and radical movements like the Situationists and curdle into the oppressive, reactionary currents of Italian fascism, each with their own visions of how to reconceive harmony for European cities in the 20th century.

These dueling and overlapping tendencies are uncannily embodied in Hangover Square, in its sense of a quiet instability moving equally and simultaneously toward potentially liberating disruption and that liberation’s imminent capacity to be rerouted into sheer brutality and hateful violence. This energy can only find refuge in a final symphony that, in combining different modalities of music, both traditional and modernist, cannot remain a guardian of classical composure and virtue without acknowledging the murmurs of uncertainty and otherness that already haunt it. The camera ultimately pans out and swirls around the artistic maelstrom Bone conjures and channels into blasphemous rage, taking ownership over the violence that haunts him, uniting his agony and ecstasy in a poesis consummated in a fire that portends the coming tremble of the 20th century. It dooms him as both a casualty of modernity and its purest form.

Score: 9/10