The ‘60s music movie, in its many permutations, was an attempt to diagnose the manifold mutations of a shifting sociocultural landscape. D.A. Pennebaker’s seminal Don’t Look Back figures Bob Dylan as an almost malevolent blank void courting and interrupting power, a clown prince puppeteering every inch of his relationship to the audience’s desire and his prismatic manipulation of it with Warholian ineffability and Keatonesque implacability. Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night frames The Beatles as impish vagabonds harnessing the recalcitrant energies of an unreconstructed, uncontained modernity. Bob Rafelson’s Head, not to be outdone, mounts a vision of The Monkees as tortured poets of a world gone awry and unable to put itself together again. In these films, without always stating it, pop culture becomes a battleground for the fate of the future and an exploration of the limits of authenticity. In rock and folk music, the cinema of this era discovered a way of interrogating film’s very capacity to index reality itself. What, finally, did it mean to “document” truth when truth itself was a maelstrom, in which the method of inquiry itself – the visual representation of reality – confronted a subject that made visuality itself an unstable ground.

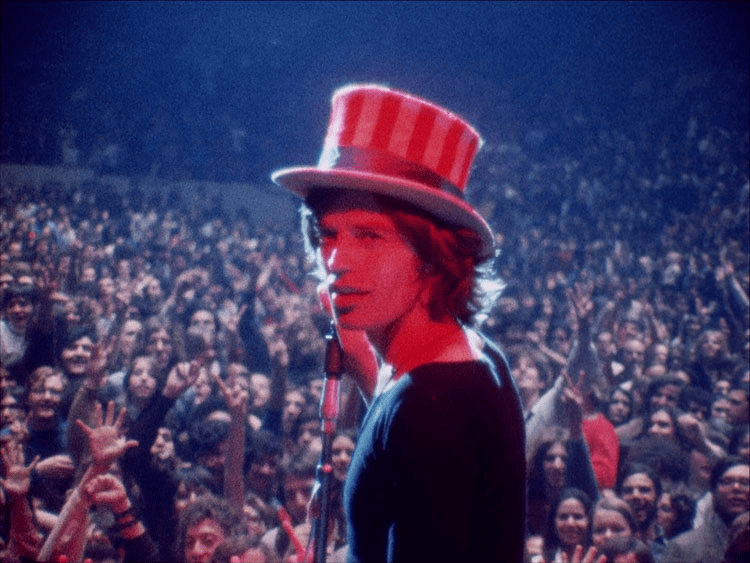

Gimme Shelter, a searingly banal documentary by direct cinema auteurs Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, seems, at first glance, to exhibit no such complication. Nor does the film’s subject, The Rolling Stones. Unlike Dylan, they do not thrum with calculated incalculability. They exhibit none of The Beatles’ self-aware, rakish charisma or peripatetic malice. When they are off-stage, they seem neither prey to nor predators of the forces that the Monkees found themselves wound up in. For the most part, they seem entirely unaware of the world around them, abstract ciphers approached by unknowing cameras.

The aforementioned movies and the aforementioned musicians all project a sense of interdependence and estrangement from the cultures that produce them. They are complex arrays of personal and social complexes, reflecting the ambiguities of gazes and desires that are offered, given, rescinded, and contested. Gimme Shelter, conversely, more or less depicts The Rolling Stones, who seem so happy to characterize themselves as willful collaborators with dark forces in songs like “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Paint it Black,” as entirely helpless. Gimme Shelter punctures the air out of countercultural acts of self-mythologization and optimistic social liberation not, as is usually written, by freighting these aspirations with self-inflated import and forcing them to confront a demonic ground labelled “the end of the 1960s.” What the film offers is more frightening and more thoroughly deflationary. Gimme Shelter implies that it may have meant nothing at all in the first place, that its most shining surfaces may have had much less going on underneath.

Continue reading