Arthur Penn’s name doesn’t linger in the cinematic imaginary like many of his New Hollywood co-conspirators. Like Robert Altman, he was an older man when the movement kicked into high-gear, which meant that he was not a product of the film school generation. Unlike Altman, however, he did have a background in commercial cinema and television. In other words, he didn’t cut his analytic teeth examining every nook and cranny of the ‘60s European interpretations of the American cinematic mavericks of the ‘40s and ‘50s. He developed his eye and hand by making those sturdy, silently subversive, culturally neurotic mid-century American films in the first place, which places him on a continuum with, say, Anthony Mann, Don Siegel, and Robert Aldrich rather than Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. He was less a student of the cinema of American waywardness than a traveler of American waywardness himself.

Befitting his journeyman sensibility, Penn’s films offered a more subliminal, less self-consciously auteurist perspective of what directing might mean. His sensibility was rooted in looking at reality through an odd angle in a mirror rather than, as his younger New Hollywood contemporaries would, shattering the mirror and holding up a serrated shard to reality’s throat. This scrappy, less avowedly personal stamp wasn’t necessarily a moral vision per-se, but the quiet compassion with which Penn contoured the emotional universes of his down-on-their-luck renegades reflected a serious empathy with the mundane nonetheless. One can think of him more as an extractor perceiving momentary realities than an artificer wholesale reconstructing that reality and conjuring meaning out of cinema’s defamiliarizing smoke and mirror show. His was a cinema of the silent tremor, not the sudden eruption.

Fittingly, then, Night Moves passes like a ship in the night, submerging a sinister vision of existence into a relatively streamlined neo-noir, one that seeks simply to embody the genre rather than deconstruct it with antic Altman-esque inconclusiveness (a la the masterful The Long Goodbye). Perhaps because it only embodies it – and doesn’t seem to want to say much about it – Penn’s film is able to explore reality’s smoke and mirror show, the minutiae of everyday subterfuge, without having to expose itself doing as such. Night Moves has as much to say about the era as any other film produced during its time, but it only tips its hand in a single scene of a man looking at a film, one which structures the entire narrative, transforming it from a narrative mystery into a Hitchcockian analysis of the act of looking. By the film’s end, we realize we’ve wandered from a distance into a narrative we thought we could watch and keep away from, before we realize that the narrative we thought we were watching and not participating in was actually, refracted in a watery mirror, not that different from our own.

I’ll get to the scene later. But the man doing the looking is Harry Moseby (Gene Hackman), an ex-star football player turned private eye presently investigating the disappearance of sixteen year old Delly Grastner (Melanie Griffith) on the request of her step mother Arlene Iverson (Janet Ward), also an ex-star surviving off of Delly’s trust fund. Like an inverse Rear Window, this is not a film about a man who likes to look to exert power through his passivity, who wants to silently observe with the subcutaneously sinister aura, but of an empathetic man who simply cannot recognize the overlap between the cases he pursues and his own life situation. His own wife Ellen (Susan Clark), presently having an affair with a man named Marty (Harris Yulin), seems far more aware of Harry’s habit of treating his personal life like a background to the lives of others, not because he wants to exert dominion over them but because he needs something to look at to avoid thinking about himself.

And, in Penn, a director who did not command the screen and announce an imposing, forbidding architecture like Hitchcock, Night Moves has an authorial voice who similarly likes to observe and similarly pretends to pursue his narratives with workmanlike acumen while actually quietly distracting us from the emotional core driving them, and driving him. Night Moves plays like it doesn’t care, or that it doesn’t matter, until it can’t anymore. As a detective film, it slowly circles around a mystery that isn’t really the point, and doesn’t really work up any steam until the final third, when nearly every occurrence suddenly compounds, or, rather, every character suddenly collapses inward into a story whose gravitational pull has been exerting its control over them, forcing them into the circle they orchestrated but could not recognize. Like them, like Harry, the film seems all too comfortable watching, until it realizes that it is much closer to the center of the storm than it knew.

For his part, Harry tries to make sense of a story he is at once apart from, drawn to, and an echo of his own life. When he follows Delly to the Florida Keys, he meets her step father Tom Iverson (John Crawford) and his girlfriend Paula (Jennifer Warren), and he makes the mistake of caring for both Paula and Delly, and of believing that his escape to this other American frontier, this liminal American outside, is a means to be a good person free of the tribulations of Southern California subterfuge, venality, superficiality. He wants a more authentic life, one unencumbered and uninfected by his history as an ex-star, Delly’s mother’s obvious disinterest in her daughter as she tries to keep up appearances of wealth, and of the conniving types he knows who spend their lives professionally manufacturing tools and mechanical devices for films.

Thus the single scene where the film reveals its meditative core: Harry watching a film of an accident back in Los Angeles involving Delly and Hollywood stuntman Joey Ziegler (Edward Binns). Penn frames Harry as a viewer in a theater, before moving the camera into a tighter focus on just the film being watched, forcing us to focus in, to clarify a voluminous expanse into a tighter narrative, suggesting that detecting the truth, divining the criminal act out of the façade, is a matter of immersing oneself in the artifice, and potentially losing one’s grasp on the difference between looking and experiencing, reality and fiction. Although this is the only scene in the film in which Harry is literally watching a movie, Penn repeats this composition throughout, signaling that Harry fancies himself an observant caretaker of humanity who also doesn’t know what the difference is between watching a story and acting in it. When Harry later confronts a pivotal suspect lounging by a pool, showing very little apparent remorse for a recently deceased person, he is again framed as a viewer on a domestic aquarium scene, a kind of cinema in which he is both privileged, relative to the uncaring object of his gaze, and at a loss, in the dark, insofar as he is the only one who is unwilling to admit that the surface superficiality they live in is really who they are. For them, cinematic artifice is life. Harry’s most cinematic fantasy is that he believes they can be separated.

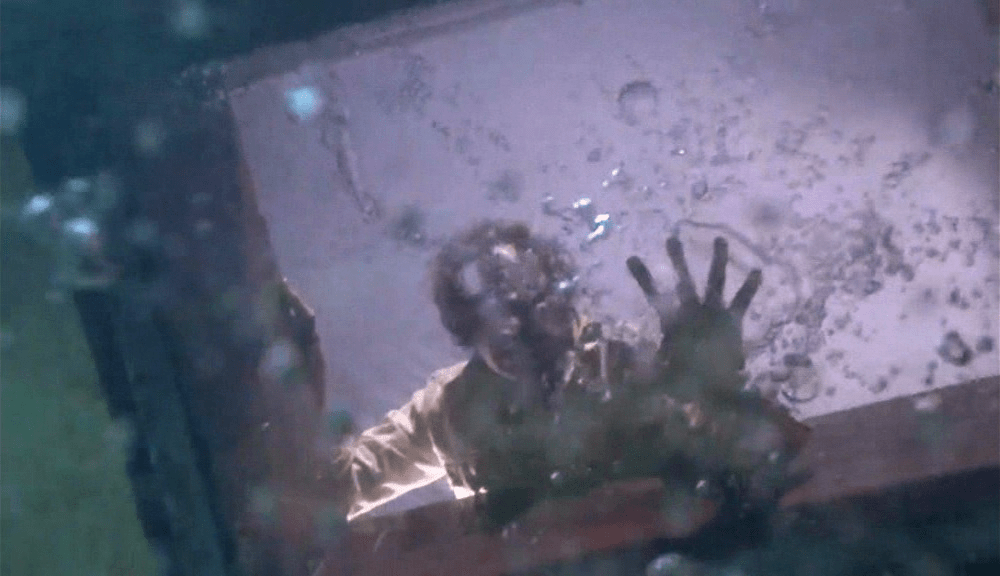

The transparent window at the bottom of a boat becomes the film’s most poetic, recurrent, and final movie-going experience. When Harry first looks down into it, he’s watching Delly discovering an underwater plane wreck, a liminal portrait of a freewheeling spirit in cosmic serenity with the world that suddenly encroaches on a violent current travelling in similar circles, one that was in fact always wrapping its tendrils around the characters.Near the end of the film, we again peer down into the depths, Harry now looking at a movie stuntman who has tried to kill him, presently drowning in his own, now underwater, plane. The boat itself has taken on water, lapping up against Harry’s ostensibly uninfected, clean side from within the boat, transforming the window from a clean bifurcation between a normal, mundane world and an underworld of Dionysian revelry and unspeakable chaos into a muddy, cinematic netherworld where Harry is neither in or out, up or down, dry or doused. If you didn’t know who was below who, either man in the shot-reverse-shot could seem like they’re presently dying.

They both are. One is just doing it more slowly. Harry got out of stardom long ago, and now he mostly circles around it, uncovering its secrets, or covering them up, maintaining a cynical distance that isn’t really a severance. He orbits around a kind of death, or something he views as a kind of death. The man drowning in the waterlogged plane still makes a living as a stunt coordinator on a Hollywood film set. He lives within death, and he is so cynical that he has no problem enacting it. We learn that he, like nearly everyone else in the film, is actually smuggling Native American artifacts from Mexico into the U.S. Hollywood subterfuge becomes an act of cultural appropriation. The man pays the price for it all, but it is Harry who is left looking through a partition where one vision of people violently living out fantasies and dreams, and another vision of people trying to not notice these dreams, meet in a murmuring portal between worlds. Putting his hand on the boat window-screen, he’s really witnessing the events of an underground movie playing out around him, a new world that is revealed yet still entirely murky, all the more disturbing because it doesn’t really need to hide itself, and essentially not that different from the world he was already living. When asked earlier about his case, Harry responds “I didn’t solve anything, I fell into it.” The film’s final joke is that the film noir that stumbled on him wasn’t really anything that should have surprised him, a subterranean world of comings and goings that is actually just the world, not its other.

It’s the easy-going indifference that makes Night Moves so nonchalantly disturbing. When Harry responds to an inquiry about regret with “I do regret it and I wasn’t even born yet,” the script by Alan Sharp radiates both a celestial disquiet and a deflationary, quasi-comic absurdity, as though whatever is wrong with him is wrong with the world and vice-versa. There’s a real sense of inertia here, of a world that keeps spinning in no direction, a movement that Harry doesn’t even know how to be involved in even though he keeps inviting himself to care. When one character hopes for more in life, another responds with “That’s not the way it happens,” exhibiting such a casually disarming fatalism that we barely remember to notice that the man speaking it ends up using that line of thought as an excuse to do ill unto others. Night Moves thus articulates both the essential necessity, and the fundamental impossibility and emptiness, of nihilism.

Crimes in Night Moves are expressed with as much casualness. We sort of learn what’s going on, and we basically know why, and we kind of always knew from the beginning, but the interesting thing about the film’s mystery is how banal it is, how basically any solution might have served to get us where we need to go, how we don’t really need to know what this crime entails in order to know that this is the structure of the world, and that some other group in the next town is doing a slightly different version of the same thing. When Harry asks “I want to know what it’s all about,” he is consummately told that he has essentially figured it out. His response, “what are you about?,” indicates that he has made the mistake of over-investing in the goodness of a bad world. He has solved a crime, he hasn’t really learned anything of value, and the real question that occupies the film is whether he should have expected otherwise. Hackman, as the film’s ostensible star, is remarkably, wonderfully opaque in exploring these questions. He interprets Harry as a man who genuinely can’t figure out what his place in the world is, and who has mostly resigned himself to an emptiness that he can’t quite convince himself to fully accept. He alone in the film retains a capacity to be surprised at the awfulness of the world, but we also sense that he has to be reminded to be surprised in the first place.

Perhaps the film’s quietly disarming fatalism, and the film’s value as an under-the-radar New Hollywood classic, isn’t really as surprising as it seems then. Penn did, of course, direct the ur-New Hollywood film Bonnie and Clyde, and it was certainly that film that re-Americanized the French interpretations of mid-century American classics like Nicholas Ray’s They Live By Night or Joseph Lewis’s Gun Crazy, and those were, after all, films about stray tangents and errant wanderers that, in their own acts of refusal, actually spoke to the itinerant centers of their time period. Those films suggested that escape was at best a necessary delusion, that fantasies of a world with potential might only be the structuring fictions of a nation obsessed with only one particular notion of freedom. Many of the French films were, to be frank, more infatuated with the poetics of Americans myth-making than the American films themselves were. The early, American texts had fewer ideas about freedom. They simply, nervously, followed those people who did light out under the sign of freedom, following a ragged-edged arc into an early grave. Maybe there’s potential in the pressured, directionless frustrations of these rebels without causes, visions of a world unencumbered by the rules of decorum and unfreighted with social pressure,or maybe these films expose the limits of escape. Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde dramatizes that tension like a volatile, runaway social embolism, where too much air in the national body leads to an explosion of unrepentant social energy. Night Moves chooses instead to treat freedom as a perpetual circular drift around what may be a sunken center, an orbit around a black hole.As one character in Night Moves ponders, it “sounds kinda bleak, or is it just the way you tell it?”

Score: 10/10