Motel Hell opens with an absolute pip of a silent sequence, a seemingly offhand shard – as though the film started too early, or we’re watching things sidle into place – that ultimately becomes the lens through which the whole film might be viewed. As the camera fades in, Vincent (Rory Calhoun) slyly and somewhat laconically smokes his pipe on the porch of his mostly defunct roadside motel Motel Hello, the “o” flickering out and the red bathing him in a warm but hellish glow. It’s a remarkably casual, easy-going, even lethargic bit of filmmaking – nothing is really happening, except another moment in this random person’s day in anywhere U.S.A. – and yet the texture of the scene folds us into a milieu and a mood. The font of the credits itself mimics the Motel font in a simple but effective means to suggest that we, ourselves, are now entering the headspace of the hotel itself. I have to say, readers, I was instantly smitten. Motel Hell is like that: it accomplishes more than most films, yet it barely does anything at all.

I’ve been fond of saying that the ideal horror comedy doesn’t compartmentalize its scenes into discreet genres but rather plays with the contours of the genre itself. Motel Hell is both a sterling example of the claim’s validity and a thorough-going travesty of it. Remarkably, none of this really plays as only horror or only comedy or as a mixture of both. If it augurs a potential slasher mode that never came to fully pass, it isn’t an anticipation of Friday the 13th: Part VI – that franchise’s overt stab at horror-comedy – but a premonition of that franchise’s phenomenally ugly duckling, the misbegotten Part V. As with Part V, almost the entirety of Motel Hell consists of watching a seemingly endless procession of passersby wander into the film, be taken care of by the killers, Vincent and Ida (Nancy Parsons). While there is technically a final girl, Terry (Nina Axelrod), she accomplishes almost nothing and is inexplicably attracted to Vincent from the get-go. And rather than noiseless, opaque killers, Vincent and Ida are decidedly quotidian terrors, comic parodies all the more unknowable because of how banal they are.

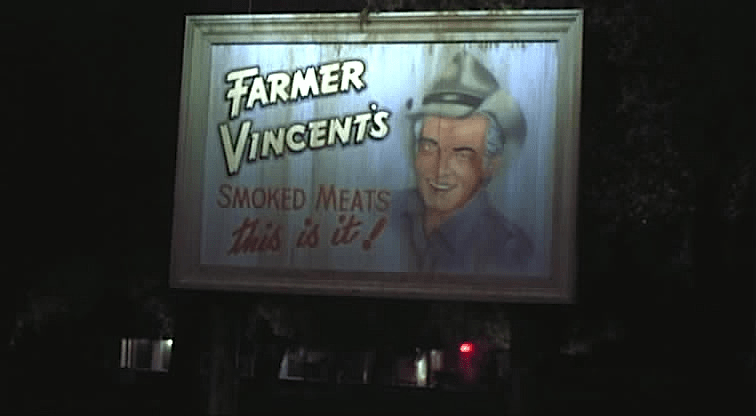

Rather than an intentional parody, then, Motel Hell feels like someone tried to prophesize a classic slasher film into being and smeared the crystal ball. As figured by Cochran, Vincent believes in his mission of providing food for America while curbing its population problem with a disarmingly naturalistic religious zeal. Playing Old Hollywood charisma as curdled charm, a kind of performative naturalism that vibes remarkably with the peculiar tonal tensions of the film itself. Tensions, I might add, which are inextricably baked into the very cinematic texture of the film. In that opening, Thomas Del Ruth’s cinematography calls forth a deeply everyday form of American demonism. The simple recontextualization of a random roadside sign, the tilting of a bright red into a phantasmic pink, becomes an uncanny channeling of the improbable in the familiar.

By the middle of the film, Del Ruth and director Kevin Connor crystallize the truly ingenious Proscenium garden where the protagonists bury their victims from the neck down, with their vocal cords severed, as they gorge them to cultivate their flavor. The lovingly devout, disturbingly paternalistic way they treat the humans like livestock is granted a kind of theater of the mind, the fervent stagecraft warping their backyard into the Grand Guignol playhouse they imagine it to be. We’re invited further in when they produce hallucinogenic fans to hypnotize their human-plants before killing them, so they don’t feel any pain. It’s as though the film is about to perform some devious act on us, and is letting us know that it knows that we’re already its prey. We’re too caught up in the act to not give in.

Although we do get our revenge. When Ida meets her demise in a frankly hilarious parody of zombie cinema with the ghouls as non-undead avengers, the warming pink of the opening scene suddenly flares into a burning crimson. We’ve returned to that introduction, which really remains the ideal lens through which to view the film, even as it grows progressively absurdist throughout. Watching Vincent and Ida simply exist in their own relatively unhurried, diligent manner is the film, which plays out less like a slasher picture than a slice-of-life story (pardon the pun, but it’s no worse than the ones the film wields) about an odd corner of America where the casual and the committed meet. American Gothic, indeed.

Score: 8/10