Love & Friendship

Love & Friendship

A lengthy sabbatical from filmmaking has clearly energized writer-director Whit Stillman, and if Love & Friendship is evidence, he has enough leftover vigor to spillover and whip long-dead, and long-enervated, authors into a frenzy as well. With this film, he redistricts the screen real estate of the Jane Austen adaptation – a genre long benighted by a paralyzing sense of respectability – toward an unhesitant embracement of her oft-misunderstood wickedness and lithe, animalistic verbal farce. Focusing on the conniving, frantic ambitions of sexual warfare subcutaneously thriving beneath the prim-and-proper rules and regulations of Victorian society, his new film feels like a vendetta against the decades of self-consciously airy beauty and antiseptic weightlessness infecting cultural assumptions and artistic interpretations of Austen and Victorian literature more broadly. With acerbic dialogue and a skewered, ruthlessly efficient visual sensibility, this is Austen set to kill. In Love & Friendship, it’s the scorching negativity that is infectious. Continue reading

Whatever your opinion of resident cinematic mad scientist Alejandro Jodorowsky, he’s not a docile creature. The Chilean director, whose El Topo ultimately helped found the inaugural class of Midnight Cinema, stages guerilla warfare against that often benighted subgenre of film with his second feature The Holy Mountain; as a work, it defies even the somewhat genre-bound surrealism of his debut and the relative sanity of most so-called midnight films which are, if more libidinous than most mainstream films, no more artistically provocative. An eyeful of imagery and a mouthful of anarchic social commentary, The Holy Mountain is a deranged field day. Replete with symbolism that Jodorowsky both embraces and mocks, this fragmented, fractal film feels like Jodorowsky’s attempt to replace all of film form with a medium more to his liking.

Whatever your opinion of resident cinematic mad scientist Alejandro Jodorowsky, he’s not a docile creature. The Chilean director, whose El Topo ultimately helped found the inaugural class of Midnight Cinema, stages guerilla warfare against that often benighted subgenre of film with his second feature The Holy Mountain; as a work, it defies even the somewhat genre-bound surrealism of his debut and the relative sanity of most so-called midnight films which are, if more libidinous than most mainstream films, no more artistically provocative. An eyeful of imagery and a mouthful of anarchic social commentary, The Holy Mountain is a deranged field day. Replete with symbolism that Jodorowsky both embraces and mocks, this fragmented, fractal film feels like Jodorowsky’s attempt to replace all of film form with a medium more to his liking.  With the pleasurably amusing The Nice Guys, writer-director Shane Black isn’t exactly treading on unstable ice; this ‘70s-riffing buddy comedy with a capital-B is the platonic ideal of a Shane Black movie released in 2016. Returning to his roots after his one-and-done tentpole picture Iron Man 3, itself an obvious get-out-of-jail attempt to rekindle Hollywood’s favor, The Nice Guys is a snarky, spiffy, not-too-smug time waster in Black’s best blowing-off-steam mode. It lacks the thorny neuroticism and paranoia of Black’s best screenplay, Lethal Weapon, or the zippy post-modernism of neo-neo-noir Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, his debut as a director. But the restless brio and cheery malfeasance of The Nice Guys is sufficiently delectable in a more straightforward, and refreshingly non-ironic, way nonetheless.

With the pleasurably amusing The Nice Guys, writer-director Shane Black isn’t exactly treading on unstable ice; this ‘70s-riffing buddy comedy with a capital-B is the platonic ideal of a Shane Black movie released in 2016. Returning to his roots after his one-and-done tentpole picture Iron Man 3, itself an obvious get-out-of-jail attempt to rekindle Hollywood’s favor, The Nice Guys is a snarky, spiffy, not-too-smug time waster in Black’s best blowing-off-steam mode. It lacks the thorny neuroticism and paranoia of Black’s best screenplay, Lethal Weapon, or the zippy post-modernism of neo-neo-noir Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, his debut as a director. But the restless brio and cheery malfeasance of The Nice Guys is sufficiently delectable in a more straightforward, and refreshingly non-ironic, way nonetheless.  Krull

Krull I meant to get to these a few months ago, but they’ve lingered around. With Batman vs. Superman continuing Warner’s desperate investment in doing the Marvel/Disney thing, here’s a look at some franchise-fighters to have come before. A note: We’re keeping this literal this time, much as I wanted to get cheeky and include something like Kramer vs. Kramer.

I meant to get to these a few months ago, but they’ve lingered around. With Batman vs. Superman continuing Warner’s desperate investment in doing the Marvel/Disney thing, here’s a look at some franchise-fighters to have come before. A note: We’re keeping this literal this time, much as I wanted to get cheeky and include something like Kramer vs. Kramer.

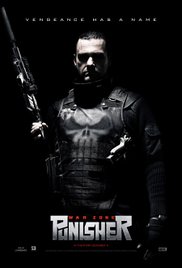

Meant to get to this a couple months ago, but better late than never. With that Daredevil “Punisher arc” raving up a storm, I thought a review of a real dust-kicker was in order.

Meant to get to this a couple months ago, but better late than never. With that Daredevil “Punisher arc” raving up a storm, I thought a review of a real dust-kicker was in order.  The late ‘40s were a high noon for the horror genre, easily the most desecrated ghost town era for a genre that has reinvented itself time and time again. From the irrepressible expressionist deviants of the ‘20s to the chiaroscuro nightmares of the early Universal films in the ‘30s to the sly, insidious Val Lewton carnival of the early ‘40s, horror was on a hot streak for decades until it hit the ice wall of WWII. Not that the real world horrors of the war inherently superseded the desire to thaw out the terror of the cinematic variety, but the will to nightmare was to be discovered somewhere else until the dawn of the atomic age ‘50s films, before horror would draw its fangs and get downright pernicious with the turn of the ‘60s and the prestige variant of the genre in the New Hollywood of the ‘70s. In the century of cinema thus far, only the late ‘90s can go blow for blow with the late ‘40s for sheer abandonment as horror packed up and went out to the country to cool its heels.

The late ‘40s were a high noon for the horror genre, easily the most desecrated ghost town era for a genre that has reinvented itself time and time again. From the irrepressible expressionist deviants of the ‘20s to the chiaroscuro nightmares of the early Universal films in the ‘30s to the sly, insidious Val Lewton carnival of the early ‘40s, horror was on a hot streak for decades until it hit the ice wall of WWII. Not that the real world horrors of the war inherently superseded the desire to thaw out the terror of the cinematic variety, but the will to nightmare was to be discovered somewhere else until the dawn of the atomic age ‘50s films, before horror would draw its fangs and get downright pernicious with the turn of the ‘60s and the prestige variant of the genre in the New Hollywood of the ‘70s. In the century of cinema thus far, only the late ‘90s can go blow for blow with the late ‘40s for sheer abandonment as horror packed up and went out to the country to cool its heels.  Although Universal was nearly dead in the water by 1946, RKO’s Val Lewton-Jacques Tourneur B-movie cavalcade was just a few years past its prime, and Warner Bros. The Beast With Five Fingers, released in that year, isn’t a patch on the dueling acmes of that cluster: the impossibly well crafted Cat People and the impressionistic, lyrical I Walked with a Zombie. So obviously, and honestly, we’re grading on a curve with The Beast With Five Fingers when we champion it – after all, this was a year in which the near-dead quasi-corpse of the genre was struggling to let its vaguely beating tell-tale heart be heard. But, with Warner Bros. playing Universal Horror for the only time in the whole decade, The Beast With Five Fingers is about as studious and sturdy an update of the even-then hoary Old Dark House format as you might imagine a struggling studio to release when they were stepping their toes in the sand of a genre that wasn’t really their own.

Although Universal was nearly dead in the water by 1946, RKO’s Val Lewton-Jacques Tourneur B-movie cavalcade was just a few years past its prime, and Warner Bros. The Beast With Five Fingers, released in that year, isn’t a patch on the dueling acmes of that cluster: the impossibly well crafted Cat People and the impressionistic, lyrical I Walked with a Zombie. So obviously, and honestly, we’re grading on a curve with The Beast With Five Fingers when we champion it – after all, this was a year in which the near-dead quasi-corpse of the genre was struggling to let its vaguely beating tell-tale heart be heard. But, with Warner Bros. playing Universal Horror for the only time in the whole decade, The Beast With Five Fingers is about as studious and sturdy an update of the even-then hoary Old Dark House format as you might imagine a struggling studio to release when they were stepping their toes in the sand of a genre that wasn’t really their own.  Years of experience with Lucio Fulci and Dario Argento, the reigning post-Bava Italian giallo masters, will give you Stagefright. For Michele Soavi, actor and assistant director to the masters turned first-time director here, this meant conjuring up this 1987 pseudo-slasher as his big come-up. The original title, Deliria, being vastly more apposite, this is less a slasher dressed up in giallo airs than a giallo putting on slasher clothing to sneak into the mainstream so it can uncloak its true self when the moment beckons. Like any good disreputable giallo, Stagefright is a bodacious concoction of performance-art murders choreographed like installation pieces, on one hand, and pure, unbridled instinct and impulse on the other. So while the kills may be judiciously filmed and planned, Soavi never lets anything as trivial as common sense or good taste trounce on his funhouse; his film is orchestrated but never programmatic.

Years of experience with Lucio Fulci and Dario Argento, the reigning post-Bava Italian giallo masters, will give you Stagefright. For Michele Soavi, actor and assistant director to the masters turned first-time director here, this meant conjuring up this 1987 pseudo-slasher as his big come-up. The original title, Deliria, being vastly more apposite, this is less a slasher dressed up in giallo airs than a giallo putting on slasher clothing to sneak into the mainstream so it can uncloak its true self when the moment beckons. Like any good disreputable giallo, Stagefright is a bodacious concoction of performance-art murders choreographed like installation pieces, on one hand, and pure, unbridled instinct and impulse on the other. So while the kills may be judiciously filmed and planned, Soavi never lets anything as trivial as common sense or good taste trounce on his funhouse; his film is orchestrated but never programmatic.