American Gigolo is usually described as a key neo-noir text. It strikes me as a kind of anti-noir, not a text that skirts the shadows of a seemingly bright modernity but a film that has accepted how the shadows themselves aren’t as threatening when the light is so obviously hollow. American Gigolo treats noir as banal, unequipped for the violence of the modern world. This is a world that has made peace with its shadows and lacquered them in a façade of beauty.

The key moment, to me, is an encounter where protagonist Julian Kaye (Richard Gere) accosts a threatening conspirator in front of a movie theater, dwarfed by a poster of The Warriors. If that film was the apotheosis of the New York of Schrader’s most famous script, Taxi Driver, murder as a spontaneous, bodily, nocturnal emission, this film is L.A. warfare: cold, calculated, and all-too-mechanical. That 1979 film cavorts with denizens of a social netherworld, caged creatures of a modern void looking to escape it in ways they haven’t fully fathomed. They lived by the images they paint on, the masks they wear, second skins as authentic selves. They form entire sub-cultures, leaping into jeans and leather pants and each other’s personal spaces with the ramshackle, reaching energy of unbridled youth. The Warriors pounces on everything. American Gigolo is always knowingly keeping a distance from itself, aware that it lives in a world that is completely alienated from itself. It can only live in that gap, slowly stalking prey that gets trapped in the space between truth and fiction.

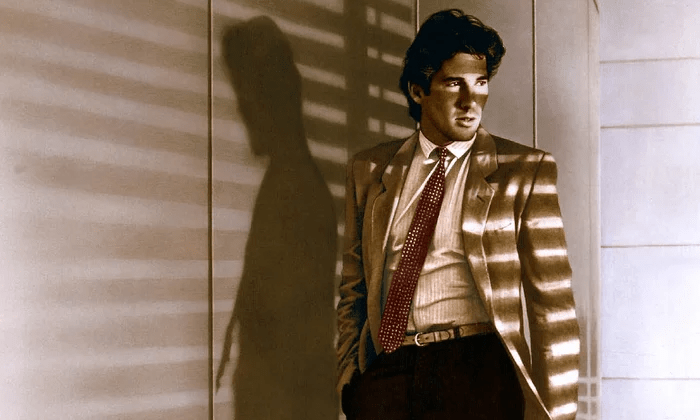

Kaye, too, is being stalked by this film. He is rendered background, wallpaper, a hastily-put-together man of disposable, posable parts sitting with leering torso images behind him. “You were frameable,” Bill Duke brutally intones near the end of the film, something the text wisely never underscores as double entendre, but it’s clearly the governing motif of the film’s mise-en-scene. A key image of him looking at himself in the reflection of a chic print writes his fate in an image. Gere’s Kaye is a walking specter of a person here, a mannequin violently controlling his self-image, manicuring every moment until he finds himself lost in an honest-to-God narrative outside his control. The trouble is that, while the narrative he steps into has its sights set on him, it is also very much the world he wants to inhabit.

Surfaces shape this narrative. They both bind it and unravel it. Kaye is a high-priced male escort for upper-class older women whose life funds and determines his lifestyle, a mode of being that he protects with a devotional fervor that borders on divine ardor. Yet he seems essentially opaque, a blank space whose zealotry is unthinking. It’s hard even to call it blind belief. He doesn’t seem to believe anything, and his reaction to being framed for a murder entangled in his work is less anger than robotic curiosity, as though saving his name is simply his automatic response to the machinery of his world being interrupted. Kaye is little more than a cog of the machine working to set itself right.

In a sense, it’s not much of a narrative then. There’s little contingency or chance. It’s a mood pretending to be a narrative, mocking us with how little is really going on in the story we’re being told to watch out for, and how much is being slipped in between the frames. The camera looms from above, something Schrader would metastasize in his next film, 1982’s Cat People. But here it evokes less a negligible line barely covering a nebulous depth – a thin strand holding a black hole at bay – than a flat, planar surface with no depth at all. It seems to watch, from above, as the world empties itself out of possible meaning. Light tries to peek in, but shutters, also from above, break up the illumination into violent black and white lines, silently fractalizing Kaye into light and shadow, deconstructing him into his component parts. The light through the blinds seems to be breaking the facade apart, fissioning the image of the man into pieces, and he either doesn’t know how to respond or can only cope with it by doubling-down on his alienated sangfroid.

The film is, in this respect, not unlike The Warriors after all. Walter Hill and Paul Schrader were two of the bastard children of the New Hollywood movement, birthed within it but in search of their other forebears, namely the chilly art-house ennui of European avant-garde cinema. The dominant texture of the ‘70s New Hollywood was spontaneous, cobbled-together, and live-wire, a vision of brutal and ragged reality tearing through the façade papering it over. Men like Hill and Schrader fold in a cryptic and impressionistic gaze that seems unsure of what breaking through the images that consume them might really mean. These directors engage modernity’s conundrums not with the ravenous, mischievous human vivacity of the ‘70s directors but with a near-apocalyptic loss of self. Where earlier films unleashed something vital and rotten underneath the surface of an apparently accepting, compassionate society, American Gigolo is all surface.

Thus, the film is all tone and texture, a collective act of stylistic theft in which the depth of the text, the possibility of a world with layers, is stolen by a cabal of conspirators insisting on the emptiness beneath their efforts. Giorgio Armani’s costumes are stark and warmly forbidding, inviting but entrapping like a Lycra straight-jacket. Ferdinado Scarfiotti’s cannily controlling production design is an open-air prison. Most devious of all is Giorgio Morodor, a man who would help redefine a decade of cinema music by turning to smooth, brittle sounds lost between analog pasts and digital futures. Here, they mark the film as a febrile commentary on modernity itself. Even the exquisite Greek Chorus of Blondie’s “Call Me” feels like an ambivalent, absolutely iridescent refrain: how much can the film do with so little, and is this a manifesto of artistic imagination or a statement of creative death?

Gigolo is too good a film to not make the case for imagination, but it requires serious moral rectitude, one that, Schrader suggests, isn’t going to come easy. In the film’s final scene, one woman sacrifices everything that her life has been building to, her entire social and public image, for a moment of personal grace. Whether or not Julian has come to understand the value of this sacrifice, after all he’s been through, remains a question mark. Putting their hands on a glass protrusion between them, one surface that finally, explicitly literalizes their separation from one another, they try to transform a canvas of alienation into a forge of redemption, a zephyr of personal authenticity to cut through the surfaces that is nonetheless formed by those very surfaces. In a deliciously ambivalent frisson, Schrader asks whether the image itself can become a weapon of something that looks quite a lot like absolution, at least on the surface.

Score: 9/10