Exploring the inexpressible, ineffable qualities of desire pressed tenuously and incompletely but immediately onto the surface of screens that cannot quite accommodate those desires but nonetheless must try to relate to them, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film remains one of cinema’s great meditations on human communication in all its valences: both achieved and failed, asked and given, demanded and foiled. For the same reasons, it remains one of the great films about the possibilities of the medium, exploring cinema at both its barest essentials and its furthest reaches. What, the film ponders, does it mean for its titular character, nominally the historical figure Joan of Arc, French hero of the Hundred Years’ War during the 15th century, to doubt and feel and desire, to commit against the flow of the world, to sense other flows unacknowledged by the powers that deny her? What does it mean for actress Renée Falconetti to essay a soul-rending performance of a woman she never knew outside of her work to recreate (and thus create) her? And what does it mean for us as viewers to confront the senses essayed in this film, largely unknown but somehow known to us, to wrestle with the very capacity of imagery to explore the possibilities and limits of representation, to represent connection across space and time? What, simply, does it mean to visualize Joan’s desire, which, the film makes clear, is unmaterial, is beyond visual comprehension? What does it mean to know a human from their face? What even is it to be interested in the material on screen?

Continue reading

I meant to get this out a month ago for Halloween, but here’s a (delayed) review of one of the great, deranged, unsung horror classics of 1968, and one which by virtue of totally refusing to put its finger on the pulse of that year, seems to encapsulate it all the more so.

I meant to get this out a month ago for Halloween, but here’s a (delayed) review of one of the great, deranged, unsung horror classics of 1968, and one which by virtue of totally refusing to put its finger on the pulse of that year, seems to encapsulate it all the more so.  A classic of Cuban Marxist-inflected cinema, director Tomas Gutierrez Alea’s La Ultima Cena offers an intimate portrait of the paradoxes that arise when attempting to reconcile “Western” Christianity and slave life on the plantation. Focused on a slave master’s self-fashioned “benevolence”, La Ultima Cena examines how slave masters’ self-regarding visions of personal sacrifice – their collective belief that they were moral patriarchs sacrificing for their slaves in hopes of “teaching” them “civilization” – couldn’t but require them to engage their slaves in ways which sometimes invited the latter to announce their humanity through means the master wasn’t likely to want to hear. Alea’s film depicts slaves themselves debating real freedom on the sham stage of a master’s faux-freedom, pushing liberation’s meaning well beyond the pale of what their master could possibly imagine.

A classic of Cuban Marxist-inflected cinema, director Tomas Gutierrez Alea’s La Ultima Cena offers an intimate portrait of the paradoxes that arise when attempting to reconcile “Western” Christianity and slave life on the plantation. Focused on a slave master’s self-fashioned “benevolence”, La Ultima Cena examines how slave masters’ self-regarding visions of personal sacrifice – their collective belief that they were moral patriarchs sacrificing for their slaves in hopes of “teaching” them “civilization” – couldn’t but require them to engage their slaves in ways which sometimes invited the latter to announce their humanity through means the master wasn’t likely to want to hear. Alea’s film depicts slaves themselves debating real freedom on the sham stage of a master’s faux-freedom, pushing liberation’s meaning well beyond the pale of what their master could possibly imagine. No special occasion here, just a re-watch for a course, and because I haven’t updated the site in a few weeks.

No special occasion here, just a re-watch for a course, and because I haven’t updated the site in a few weeks.  I originally wanted to write this up in reference to the release of Craig Brewer’s My Name is Dolemite next week, without even realizing the highly appropriate irony that the last (only?) great Blaxploitation film was released almost one decade ago to the day.

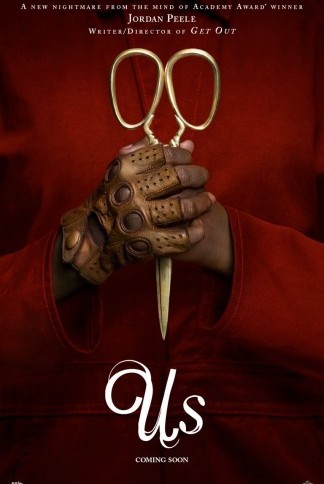

I originally wanted to write this up in reference to the release of Craig Brewer’s My Name is Dolemite next week, without even realizing the highly appropriate irony that the last (only?) great Blaxploitation film was released almost one decade ago to the day.  Jordan Peele’s Us bears many obvious linkages to Get Out, Peele’s 2017 box-office slayer, but Us feels less like a retread or even an update or extension of Get Out than a perversion, a disruption, a chaotic disfigurement of the earlier film’s elegant simplicity. Us is both more existential and more surreal, more playful and more brutal, and, above all, more experimentally distended, exhibiting a newly ravaged and warped texture that is very much to my taste, but not necessarily to those looking for a clean like of argumentation in the film, or even a clear subject. Get Out’s comparatively streamlined metaphor for sight, sightlessness, and embodiment was tight, vicious, and tenacious – perfect for itself, and perhaps for a first film – but not nearly so troublesome as Us, which actively and conspicuously refuses the snug moral logic and trimmed-down narrative of Get Out. Us isn’t avant-garde in any overt sense, but where Get Out’s story fell into place, this new film buckles, utilizing horror for its demonic textural and thematic elasticity and indescribability rather than merely as a generic skeleton for a moral parable. It’s storytelling by way of allusion, digression, and disturbance, a film that benefits or suffers greatly (depending on your proclivity) from writer-director Jordan Peele’s obvious enthusiasm overtaking his discretion, his ensuing disdain for hedging his bets and, probably, his frustration with heeding the rules and regulations of Hollywood storytelling. It’s as if, having mastered the art of skillful middlebrow horror cinema, Peele decided to dismember it.

Jordan Peele’s Us bears many obvious linkages to Get Out, Peele’s 2017 box-office slayer, but Us feels less like a retread or even an update or extension of Get Out than a perversion, a disruption, a chaotic disfigurement of the earlier film’s elegant simplicity. Us is both more existential and more surreal, more playful and more brutal, and, above all, more experimentally distended, exhibiting a newly ravaged and warped texture that is very much to my taste, but not necessarily to those looking for a clean like of argumentation in the film, or even a clear subject. Get Out’s comparatively streamlined metaphor for sight, sightlessness, and embodiment was tight, vicious, and tenacious – perfect for itself, and perhaps for a first film – but not nearly so troublesome as Us, which actively and conspicuously refuses the snug moral logic and trimmed-down narrative of Get Out. Us isn’t avant-garde in any overt sense, but where Get Out’s story fell into place, this new film buckles, utilizing horror for its demonic textural and thematic elasticity and indescribability rather than merely as a generic skeleton for a moral parable. It’s storytelling by way of allusion, digression, and disturbance, a film that benefits or suffers greatly (depending on your proclivity) from writer-director Jordan Peele’s obvious enthusiasm overtaking his discretion, his ensuing disdain for hedging his bets and, probably, his frustration with heeding the rules and regulations of Hollywood storytelling. It’s as if, having mastered the art of skillful middlebrow horror cinema, Peele decided to dismember it.