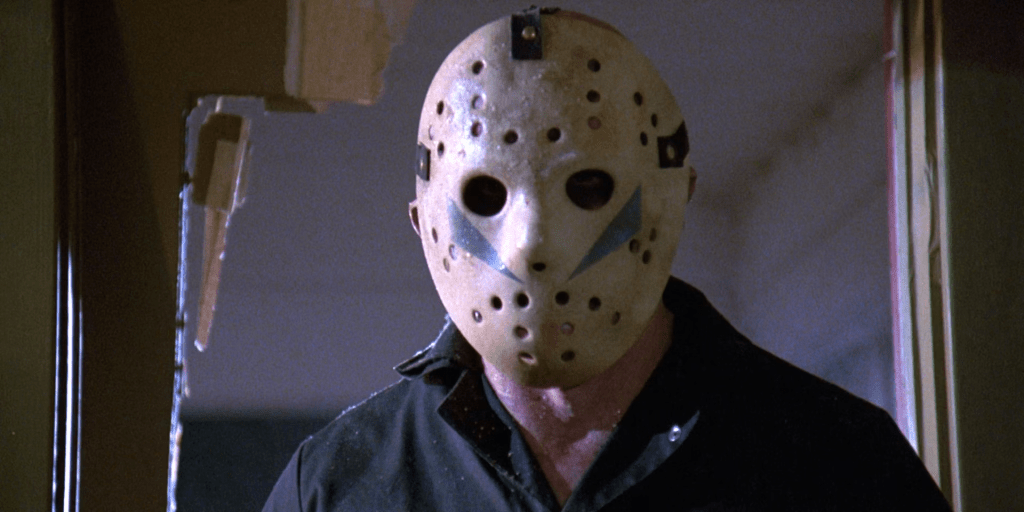

Having formally killed its Hockey-mask-clad central protagonist, Friday the 13th Part V: A New Beginning had nowhere to go but sideways. With the nominal franchise tetralogy concluded, but without the courage to shift away from the machete-wielding killer, the producers of Friday the 13th Part V took the cheapest possible route they could find. Rather than shifting to an entirely different story, a la Halloween III, or evolving the killer to include new emotional registers and shades of hate, a la Nightmare II, Friday Part V simply puts a new guy in a new hockey mask. His identity is technically a mystery but also entirely irrelevant and, famously, barely revealed in the moment of his ostensible, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it revelation. That may seem like a failure on the film’s part, but it also, oddly, recalls the spirit of a famous Edmund Wilson article called “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?” Focusing on an arbitrary narrative mystery asks the film to reduce itself to our conventional standards for judging cinematic quality. Does the identity of this killer matter? Could it? What does it say about us that we would want it to in such an empty film to begin with? Those conventional standards are fine if the film in question wants them, but Friday the 13th Part V is up to something, hacking its narrative to such tatters with Jason’s machete that it barely even registers as a film at all. Why can’t we search elsewhere for meaning?

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: A Nightmare on Elm Street II: Freddy’s Revenge

A Nightmare on Elm Street II: Freddy’s Revenge is a strange film to watch retroactively. It clearly isn’t yet fully aware of the expected texture of a Nightmare on Elm Street film because the weight of expectations hadn’t yet fully set in. But it’s also more liberated to follow its own energies, to treat the first film as a possibility to explore rather than a canvas to recreate on a larger, more absurdist scale, as the later films in this franchise did for better or worse. While Nightmare was a blinding light of cosmic terror, and the successive films would double-down on this formula to terribly successful (III) and just plain terrible (Freddy’s Dead) ends, the first sequel is a different creature all together. Queer in more ways than one, the film’s self-evident sexual subtext is all the more extraordinarily disarming because of how lurid and tortured it all is, like a film that hasn’t so much theorized its subject as felt it in its loins. Like its subject, this film is so unsure of itself and its structure that it seems to unleash energies it cannot quite explain or control. It is inverting formulas that it didn’t even yet know existed, partially lashing out at its forebears with a desire to be different and partially, simply, just not caring.

To its credit, if sex is typically associated with moral judgement or parental anxiety in slasher cinema, Jack Sholder’s film clearly fames the problem as a lack of climax. This film in no way believes, even as a product of unthinking corporate osmosis, that teenagers should not have sex, nor that they should be subjected to immediate death if they wish to. This Nightmare self-evidently believes that sexual frustration of all stripes is the culprit, and that identifying and being true to one’s even unrecognized sexual desires is an unambiguous good. “Subtext” is the word that is often brandied about in discussions on this Nightmare, but this is really only because the film is generally more interested in disturbing and trespassing on its own territory than making sense of anything in particular, and because it plays by the ruleset of its own id rather than developing any particular argument. There isn’t a “text” here to work with, just many stray feelings and sensations vying to be made manifest, repressed and latent urges in need of being rendered on the surface. For a mid-‘80s horror film, this is no simple thing. This is the feel of a film either not quite sure what it wants to say or so sure that it starts to drip off the screen. That, of course, makes it a more worthwhile film in more ways than one. That the film achieves this through a mostly nonsensical metaphor is either a feature or a bug, and no reviewer can determine that for you.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Halloween III: Season of the Witch

It’s hard being Halloween III. To its detractors’ credit, the film barely makes a case for itself. It hardly even feels like a film. So much happens, all of which feels like it was hashed-out the day after it was filmed. You have to give John Carpenter and Debra Hill credit for patently wanting to reach out in new directions, to thoroughly divest from what made the first Halloween such a cultural and commercial touchstone. Their desire, it seems, was so palpable that they allowed such a thinly-sketched, hardly-convincing story to tell the tale. If Michael Myers was a demonic moan of horror minimalism as a descent into suburban abjection, this one is a positively demented howl of absurdist maximalism, high concept and even higher in its demand that we don’t question it. This is an unhinged film, one that goes way out on a limb with its conspiratorial vision of corporate control and capitalist satanism.

Yet Tommy Lee Wallace, who directs with much more control and precision than he writes, doesn’t really seem to commit to the bit. Ironically, this is the film’s saving grace. In treating all the material with a kind of nondescript superficiality, in not trying very hard, it gives the film an air of offhand, blasé malevolence that is hard to dismiss, even if it is easily mistaken for mere uncaring banality. And it is entirely befitting the subject matter, which examines a decidedly more strait-laced and corporate wickedness than the prior films in the franchise. Evil, Hannah Arendt famously wrote, is banal after all, and Season of the Witch is a delirious mix of the thoroughly evil and the positively banal.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Two Versions of The Fall of the House of Usher (1928)

The Fall of the House of Usher

Jean Epstein and Luis Buñuel’s adaptation of Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Fall of the House of Usher, in no uncertain terms, does not meaningfully understand the themes of the Poe story at all. Yet, at the same time, it absolutely nails the texture of it, even as it mutates that texture to alternative ends. Eschewing the story’s haunting, morbid diagnosis of humanity’s capacity for obsessive monomania, Epstein’s film evokes a romantic mood of sepulchral loss and lonely frustration, of wounded togetherness longing for fulfilled desire. Nonetheless, while it veers heavily from Poe’s intentions, it does resonate with Poe’s spirit, weaving a dense shroud of despondency and bitter regret that suggests Poe’s lovelorn, troubled life and the desolation that so frequently found their way into his pen. It’s more of gothic romance than gothic horror, but the way in which the world itself seems to lament the miscommunications of the characters is vintage Poe.

More a situation than a story proper, Epstein unchains cinema from reality and explores its expressive potential as a channeler of desire. Epstein’s film retains only the barest bones of Poe’s story, as an unnamed guest (Charles Lamy) visits his friend Roderick Usher (Jean Debucourt), who is painting an abnormally lifelike portrait of his wife Madeline Usher (Marguerite Gance), who, we are told, is dying. But this is more a pretext for the camera to resonate with currents of emotion lying underneath. When Usher plays a sonic lament for his wife on guitar, Epstein intercuts undulating waves that makes it seem like he is making the heavens move, or that they are weeping for him. An aria of billowing drapes suggest that the house too howls, as though cinema itself is reverberating with his consciousness. Nature, via cinema, seems to test architecture’s capacity to withstand.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Demons

Demons is clearly up to no good right from the log-line: a group of movie theater attendees invited to an advance screening of a new horror film become demons, consumed by the film-within-a-film’s sheer vitality. Metaphoric subtlety is not this film’s strong suit. By the time we’re 15 minutes in, there’s precious little mystery about what is afoot. Then again, restraint isn’t everything when a director knows how to channel obviousness into a kind of cinematic blunt force trauma. Demons is a cinematic demiurge, a fearless force of a film that opens with a gambit so idiotically overbaked that it can’t but sell you at the cost of its, and your, own soul. For the first third or so of the film, we watch the characters watch the film, cutting, with almost equal screen time, between the film and the film-within-a-film, as the two oddly resonate and rhyme with one another. Metaphysical events on screen mimic metaphysical events on the screen within a screen. The dead come back to life in both. It’s so obvious and inane that it becomes subtle. Almost entirely at a formal level, the film posits that the cinema theater is itself a centuries old crypt, and that film watching is an act of necromancy, a portal to the past but also to the unholy regions of the soul.

Without much metanarrative shenanigans – with no Scream-like characters discussing films within the film, with only one brief speech about the dark art of cinema, and even then one that doesn’t even seem to believe itself – Demons justifies its existence by asking one simple question: are you actually seeing the film you are watching? What does watching do, and how does how you watch this film reflect something broader about the act of watching itself? I don’t mean simply that it meditates on the act of watching at the level of the screenplay; I mean that it actually asks us to assemble the connections between the film and the film-within-a-film, which are purely visual and associative, never remarked on in dialogue.

Now, the film itself hardly earns the lofty comparisons, and more than any high-minded philosophical gambits, it’s just as easy to see Demons as a demented bit of autocritique in which cinema has fun excoriating itself, enjoying its own act of assaulting us just for the hell of it. But perhaps the superficial spirit of pure play is the point. Sometimes, you try to make a masterpiece. Sometimes you try too hard and fail. Sometimes your film works in spite of itself. Rarest of all is the film that tries and fails, and doesn’t even really make its point with a lot of sophistication, and still somehow justifies its existence through sheer gusto, as though channeling some cinematic otherwise entirely. Which, of course, places this film right in the heart of giallo, the sub-genre of Italian horror that always managed to strand lone, happy-go-lucky Americans in European cities tormented by the undigested weight of history and the centuries of violence lying in weight beneath the surface. The genre, most famously shepherded by Mario Bava and Dario Argento, turned the film space into a veritable vortex of phantasmic energies and stray forces with designs on our nerves, an attempt to render visible those currents typically operating below the perceptual threshold. Demons is the calling card of Bava’s son Lamberto, and there’s a sense in which turning the film’s assault back on cinema itself is its way not of answering the genre’s questions but extending its energies. It’s as though the younger Bava needs to exorcise the demons of the genre his dad created.

The film itself fashions a thoroughly cosmic vortex of impressions and sensations, signs and wonders, beyond any realistic or geographic space. A portentous crimson seeps up from the shadows only to dance with an azure aura of crystal menace. And the elder Bava’s favored yellow seems to emanate from some putrescent sickliness caking the screen, including in a putrescent looking bathroom that seems to have been coated in puss. We submerge in a thoroughly undomesticated space.

The film has no real interest in domesticating it. When one character hears of the 16th century prophet and remarks “Nostradamus, sounds like a rock group to me,” the comment obviously satirizes her inelegance, her inability to wrestle with genuine history and the sort of predictive capacity it portends. She can’t see the ability of history to prophecize the future because she is too stuck in her own present, too entombed in ‘80s corporate culture, to notice. At one point, a cut of a downward knife in the film-within-a-film transitions to a woman moving in the same downward direction to look away from the violence on screen, unknowingly repeating it with her body. We, the film suggests, are possessed long before we start hunting for flesh.

But what is the film’s own suggestion other than that modern art itself constitutes its own divining rod, that it allows us to see better than we otherwise could, that pop cinema is part of a prophetic lineage? Art has haunted us, has us in its grasp, and that is a many-centuries-old pull, not a mere modern phenomenon. Early in the film, a key transition equates the projector in the film theater with the two headlights of a motorcycle in the film-within-a-film, which soon enough finds an echo in the flashlight of a movie theater usher. All of these seem to tease us with a direction, the hope of being guided somewhere, to something, but amidst all the light and shadow, just what we are meant to see, and how anyone could see it, is really the film’s thorniest conundrum. Bava shoves knife after knife (literally) into the assumption of cinematic sanity, into our ability to properly separate art from reality, to ground our viewing experience in prefigured ideas about the nature of the reality the film is conjuring. Demons is doing some fearless business chasing a metaphor it can’t quite earn, but bless it for trying.

Score: 8/10

Midnight Screamings: Monkey Shines

There’s a lot of mud around slung in Monkey Shines, and a lot of mess to survive if you want to appreciate it. It’s a sloppy film, in too many ways, in too many directions, but it genuinely tries to burrow into humanity’s bowels in search of a rich vein of terror. It was writer-director George A. Romero’s first studio picture, and his last for quite a while, the obvious fruits of his successes with his genre-defining Dead trilogy. It also reflects a kind of conceptual challenge to himself. While his most famous films redefined the zombie genre, clarifying one kind of fear rooted in mobile bodies unable to be controlled by unthinking brains, Monkey Shines inverts the dynamic. Focusing on Allan (Jason Beghe), a man who is rendered a quadriplegic after a running accident but retains full control of his “civilized” brain, Monkey Shines turns the loss of physical motion into a carnal meditation on the nature of masculinity, into whether a functioning brain is enough man for a man to accept when he doesn’t feel at home in his own body anymore.

Ironically enough, it’s a bit like John Carpenter’s studio horror picture Christine in that regard, but rather than a turning to man’s inner machine, Romero tries to dissect an inner beast. When Allan’s friend Geoffrey (John Pankow) recommends a trained chimpanzee to provide companionship and perform small tasks around the house, he neglects to mention that Ella has been injected with an experimental drug designed to boost her intelligence, and that companionship with Allan may be what she needs to excite the mind. While things initially work out for the better, Allan’s rage issues seem to metastasize almost instantly, and he is also receiving visions of something running outside with an oddly simian gait, despite Ella ostensibly being locked in a cage. More than a scientific symbiosis, the relationship is a kind of mental merge between the two, with Ella coaxing out the rage in Allan and Allan galvanizing Ella to act.

There’s a lot packed in here, and Monkey Shines is an odd beast, one that mixes metaphors and both over and underexplains itself. The film’s narrative makes a kind of hash of its themes. Is Allan’s anger metastacized by the psychic attachment to Ella, or is Ella simply acting on an already violent personality, which we aren’t given any clues of beforehand? Are the outburst latent manifestations of his frustration or is it restoring something that was always there? Poignantly comparing himself to a machine in an early moment, the film doesn’t need the underscore of the scene’s on-the-nose final line to clarify the point that his masculine self-possession has been underwritten by his organic nature, his physical and bodily masculinity, and that he feels threatened without it. More poignant is a brief, unremarked comment by Melanie (Kate McNeil), Ella’s trainer: “she’s your slave,” implying that mastery over an animal is his way of feeling whole again.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: A Bay of Blood

At the dawn of the 1960s, a number of Italian directors came to prominence with the rise of world cinema (or, rather, the construction of “world cinema” as an idea). Among the most famous, and certainly the most invested in dissecting the tensions of modernity, was Michelangelo Antonioni, whose 1960 film L’Avventura spreads outward in search of an exit from the present rather than following its line. Following two people who lose interest in searching for their suddenly-evaporated friend, the film suggests the limits of the detective’s epistemology, the hunt for the smoking gun. As we expect it to hone in, the film’s narrative seems to diffuse into the ether, as though something in the air and atmosphere was sucking dry the capacity to link cause to effect. Antonioni’s film suggests a search for an answer that, before long, blinds the protagonists to what question they were originally searching for. The need to reclaim a past, to resolve a conundrum, soon enough, unloosens into a wayward, wandering space where we can search around and within but not move toward.

At the same time, while Antonioni was exploring the limits of cinema’s capacity to follow narratives, prove conclusions, or answer problems, another Italian director was taking the old-school cinematic detective’s epistemology in another direction that, ultimately leads to a similar and similarly cruel meditation on the birth pains of the late 20th century. While no one would mistake Italian horror maestro Mario Bava’s 1964 Blood and Black Lace for Antonioni – it is a loving Hitchcock tribute rather than Antonioni’s tribute to all that was inadequate about Hitchcock – Bava’s films also explored the inadequacy of their own governing principles, also investigated themselves. But they did so less out of Antonioni’s deconstructionist intellect, his interest in perusing the world’s death throes, than a desire to playfully push the living to their limits. Bava’s early films nominally replicate Alfred Hitchcock’s style, but like the master, you can see him breaching unasked questions, testing and contesting their own frameworks. Bava’s bold, primary-hued splotches of color and narrative looseness, where the trajectory of the character’s arcs and the flow of the narrative become increasingly difficult to parse, suggest a touch of the surreal, a dream logic taking Hitchcock’s parts and recombining them for their own purposes just as surely as Godard did with old Hollywood gangster pictures.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: The Blob (1988)

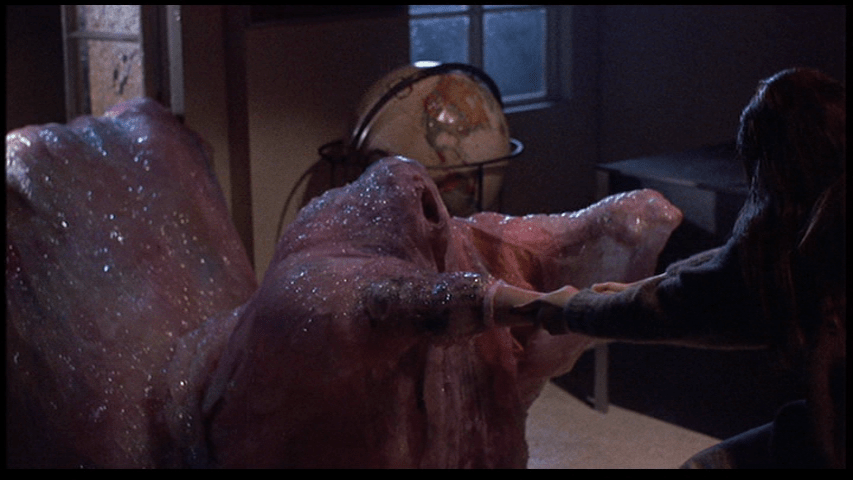

Released at the tail end of a number of remakes of mid-century horror pictures, Chuck Russell’s The Blob often gets the short end of the remake stick. If the remake trend was the fruit of the decade’s fixation with recovering, or rather creating, a mid-century optimism, the 1988 The Blob was released at the end of the trend, on the cusp of Bush-era cynicism, and is usually considered an also-ran amongst the heavy hitters of the era’s remakes. Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Don Siegel’s 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers started the trend with a new version that updated that ultimate meditation on Eisenhower-era conformism into a critique of the failures of ‘70s individualism, the exsanguinating of the possibility of ‘60s liberation into a cult of mere personal difference. John Carpenter’s brutally poetic 1982 film The Thing recognizes and laments the fact that a group of men stranded and with even a little reason to worry are fundamentally willing to destroy one another. (His Christine one year later also turns mid-century iconography and masculinity into an auto-erotic death-drive and a failure to genuinely progress, but it is not a remake). David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986) refigures Frankenstein as a post-industrial blues for the neoliberal era and a striking meditation on the human mind overtaking and corrupting the human body.

The Blob is, arguably, the least essential of these films (I wouldn’t quibble with the claim), and the comparisons arguably invite expectations The Blob itself doesn’t have much interest in validating. Plus, it only slightly precedes the end of this remake cycle and the birth of a second round of remakes: Savini’s Night of the Living Dead (1990) and a third version of Invasion, simply titled Body Snatchers, anticipating a decade of ‘70s nostalgia. Nonetheless, The Blob does feel of a piece with these earlier films. It lacks Carpenter’s meditative sangfroid and Cronenberg’s psychosexual energies and exploratory fixation on the limits of the human body, but it is, in its own way, a terse and cunning quasi-satire of ‘80s-era cultural conformity. When the film begins, a phenomenally moody, empty town suggests a derelict, post-apocalyptic hellscape for several minutes before the film cannily reveals seemingly the town’s entire population at the local football game. The titular mass of metastacizing pink extraterrestrial goo, it seems, hardly needs to get to work. Small town life has already eaten itself alive.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: The Exorcist III

Lord save The Exorcist III. While never succumbing to the dark depths that suffered John Boorman’s delirious 1977 The Exorcist II: The Heretic, writer-director William Peter Blatty’s 1990 attempt to salvage his beloved franchise from the mismanagement of other voices fared little better among critics when it is released. While William Friedkin’s adaptation of Blatty’s original book The Exorcist was a truly epochal zeitgeist hit in 1973, a refraction of social backlash to the free-wheeling ‘60s, Blatty was always uncomfortable with Friedkin’s quintessentially ‘70s quasi-nihilistic hopelessness. Following Stephen King’s own famous critique of Stanley Kubrick’s demonically beautiful adaptation of The Shining, Blatty took it upon himself to reframe the film franchise that was surely his greatest claim to fame, turning it into what he’d always intended it to be: a beacon of light in the face of unmitigated evil in the world. Suffice it to say, the resulting film wasn’t what audiences or critics, deeply enmeshed in post-Reagan era cynicism, wanted.

Friedkin’s original The Exorcist, despite barely resembling his other films, is unmistakably the work of a man who was fascinated with psychic, social, and cosmic forces assaulting porous bureaucracies and systems in crisis. The deeply disturbed Exorcist II: The Heretic, a cosmic fracas of late ‘70s entropy as the decade tried to figure out what it was up to, was simply a psychic force all itself, not a film with something to say but an energy with designs on our consciousnesses. While Friedkin was a skeptic and Boorman a crank, Blatty was a zealot. Gone from The Exorcist III are Friedkin’s muscular mercuriality and Boorman’s psychedelic maelstrom. Instead, Blatty creates a comparatively unambiguous, deeply sober examination of the potential for evil in the world, a film that could for all intents and purposes be called simplistic, even “square.” But this is certainly not for lack of trying. The Exorcist III was released during a remarkably unimpressive few years for the horror genre, and, whatever else it does or does not do, it is certainly the work of someone seething to unleash something upon the world.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Christmas Evil

I am making a New Year’s Resolution to return to blogging during the year 2024, starting with a slew of horror films in January to start the new year off on the dark side. But I had one or two holiday lumps of coal that just couldn’t wait until the calendar year switches over. Happy Holidays.

Christmas, an ostensible apotheosis of human togetherness, is also the apex of modernity’s hypocrisy and self-contradiction. While Christmas offers possibilities, it also implies assumptions and standards, and smuggles in judgement and failure. In addition to exacerbating consumerism, it metastasizes potentially possessive orientations toward compassion doled out in objects rather than genuine empathy. It is, as many have remarked, the loneliest time of year. While this isn’t a new observation, few films dissect these paradoxes as viciously and unapologetically as Lewis Jackson’s Christmas Evil. In the guise of an exploitation film – or because it is an exploitation film – it exploits the gap in our stated and performed values, scratching at it until it bleeds.

You know you’re in for something special almost immediately: Christmas Evil joins the wonderful club of films whose on-screen titles are different from their marketed titles. Christmas Evil’s in-credit title is You Better Watch Out, whose declarative claim suggests a moralistic missive which can’t quite match the blunt vagueness of Christmas Evil, perhaps the most straightforward title one could conjure for the narrative presented, but also the opaquest. “Christmas Evil” is almost totally unrevealing – it tells us next to nothing – yet it really tells us everything we need to know. It evokes the real feel of this film, a kind of brute poetry that puts in very little ostensible effort but radiates a kind of demonic sorrow. The vicious simplicity of the title anticipates a film that is both, minutely observed and deeply abstract, extremely simple and deceptively complex, a film that reveals more with every viewing, a gift that keeps on giving.

Continue reading