What does it mean to watch a murder? What does it mean to meditate on the cause of a murder? What does it mean to plan one? What does it mean to watch one being planned? To what extent are these four things different, and to what extent are they the same? “We’re just not very skillful at that sort of thing,” the film reminds us, and demonstrates, and the statement might apply to all of the above. Even when we think we’ve got a bead on what will happen to Edward G. Robinson’s Professor Richard Wanley, or what bit of evidence will or will not convict him, we keep wondering what it even means to judge someone, or to find someone guilty, or whether we can or should rely on any evidence given how easily each agentive act is contaminated by context, each exhibit for the prosecution claimed in part by chance. The ease with which the two protagonists find themselves more prepared than they expected to cover up a death and facilitate a murder, and the methodical way they begin to calculate their own moral slippage, is quietly penetrating. When the lights go up and the machinations of fate are apparently reversed in the film’s final minute, the grim realization is not that this was all an unfathomable dream but that the membrane separating determinism from contingency, demarcating sudden relief from a nightmare of existential guilt, is only molecule-thin.

Continue readingCategory Archives: Review

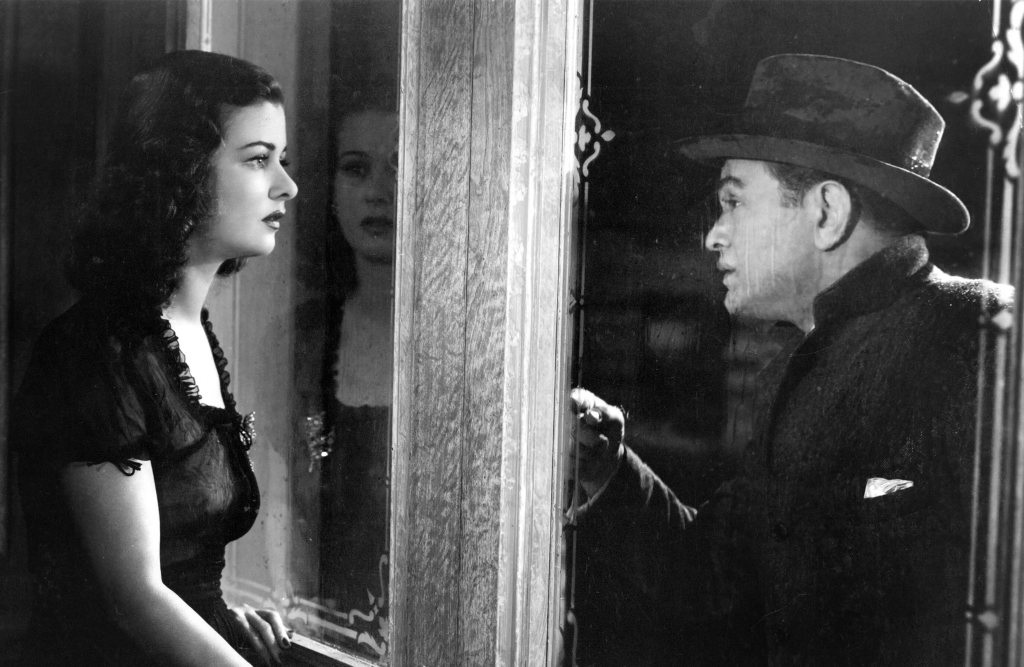

Midnight Screenings: Secret Beyond the Door

For a director most associated with expressive harshness, Fritz Lang was an abnormally varied, prismatic artist. Even his American sojourn, long considered a fall rather than a fault-line, an adventure of its own, reveals multiple distinct periods emerging out of one another. His despondent ‘30s texts, evocations of a Depression-beset nation submerged in restless ennui, are preludes to his flourishing film noir American missives in the ‘40s. Noir itself was a trend that Lang had, of course, precipitated in his German expressionist classics, but he would go on to break them down as well, essaying several coldly analytical later texts in the 1950s that abstract noir to nearly Kafkaesque levels of conceptualization, reflecting the return of European thought to a mid-century America wracked with anxiety about its Byzantine bureaucracies, corporate homogeneities, and ambivalent position in the global fight for a freedom that America had long claimed but also inhibited.

These final films were among his most despairing, anticipating the post-modern criticism of the ‘60s and suggesting that the soul-ravaging violence Lang worked through as a young man in Germany was an all-too-perfect waystation for his discovery of a more distinctly American violence. While Lang adapted to the particular anxieties of multiple time periods, from Depression-era miasma and social neglect to ’40s-era social consensus politics, he became a dark poet of life within the apocalypse at its most fatalistic.

Continue readingFilm Favorites: 12 Angry Men

In the opening minutes of Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men, justice transforms from a towering obelisk of American might into an embattled and deeply fragile conundrum. In the opening shot, the courthouse pillars leer, imposing edifices that might suggest a beatific monument to a concept solidified for eternity or, conversely, corroded into a hollow stillness. But what makes the building matter? The lawyers, who we do not see in the film, get a uniformly bad wrap, and the judge we temporarily witness seems more interested in playing with his pencil than in the conceptual, ethical, or logistical questions he doesn’t recognize are on trial (or, perhaps, he has already resigned to their assumed guilt). This seems like an evacuated justice, distorted by an unnamed McCarthyism and the daily inertia of boredom and limitation, a vaporous principle without a sturdy enough form to channel it.

12 Angry Men wants to save democracy though, or at least to argue that it is worthy of being saved, but it presents no legal armor worth a salt. This is a film in the unenviable position of mounting a battle for a principle that, it admits up front, has no army to fight for it. No formal army, that is. It is not the building, 12 Angry Men suggests, or those employed in it or by it, that form the cornerstone of American morality, but that most humble arm of democratic reasoning, the titular figures who assume they know before learning to appreciate that things might be otherwise. This, the film claims, is the soul of America, a dozen lost soldiers of democracy heretofore unknown to one another: “the people.”

Indeed, they become “the people” throughout the film. The opening tracking shot glides us through the courthouse and into the jury room, a gathering ground of difference communicated and contested, a town hall meeting in miniature. Juror #8 (Henry Fonda) marks himself as a redoubtable icon of justice by staring out the window of the room, reflection upon the wider world while preserving his own individuality, not yet fully, or only, participating in this temporary local community. When everyone sits at the table, the film christens the creation of a space of democratic give-and-take and competitive collaboration where friction produces, in theory, a truth as ragged and unfinished as it is steadfast and eternal.

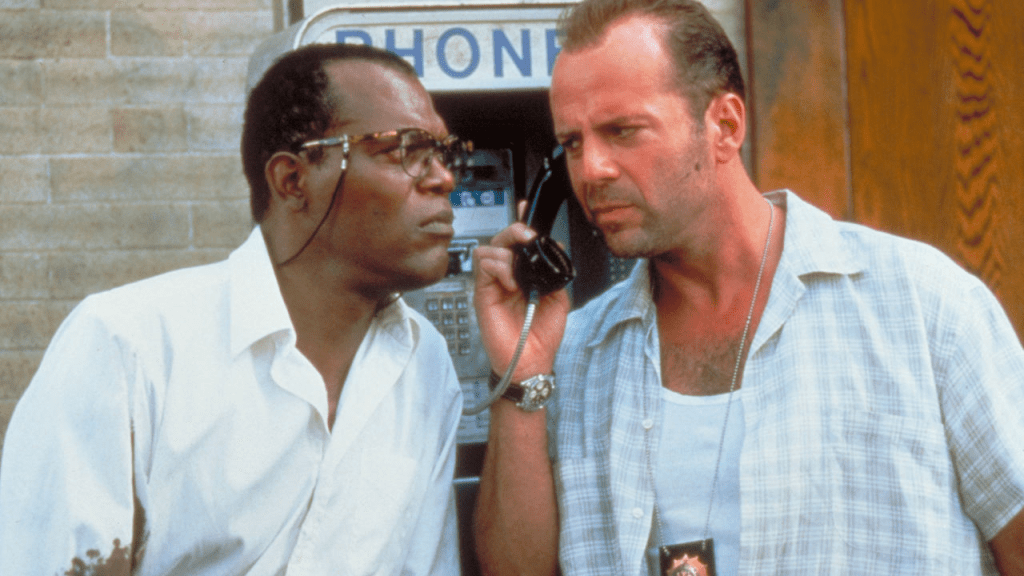

Continue readingMidnight Screenings: Die Hard with a Vengeance

People have been sleeping on this one, and Die Hard with a Vengeance is a film precisely about not falling asleep on the job. It’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the rare action movie that is interested not in demonstrating what it can show us but how it can attune us to the act of showing. So many times throughout this film, the camera gracefully and sinuously pivots around a character’s face and then zooms inward to the object of a dawning realization, either across the street or across the city, a recognition that consistently signals something is afoot but seldom explains what, exactly, is going on. Director John McTiernan repeats this maneuver so often throughout Die Hard with a Vengeance that it becomes a nervous tic, tweaking the text into a series of variations on a theme, a tilted, post-modern blockbuster for a tumultuous world.

Die Hard with a Vengeance is a highly-strung text, a film for the masses with the movements of the masses on its mind. For the series protagonist’s first film back in New York, John McClane’s ostensible home, the film dedicates itself to making us feel like a stranger, casting us adrift, unanchored, through transportations, transmutations, and teleportations. Die Hard with a Vengeance feels like the anti-Die Hard, and no surprise. Star Bruce Willis only agreed to return if the film zigged when the earlier texts zagged. Rather than the first film, a vicious bottleneck, Die Hard with a Vengeance splays outward, a murderous carousel rushing us back and forth while also tacitly and gravely intimating that it’s having maniacal fun with us. (Speaking of which, this film walked so that Fincher’s The Game could run.) An episode at Yankee Stadium is just the film giving the characters and the audience the runaround, showing us a New York City landmark merely because what would McClane’s return to NYC be without it? This is a rich, relational film about what it means to get across a city like this, and what it means to survive through it.

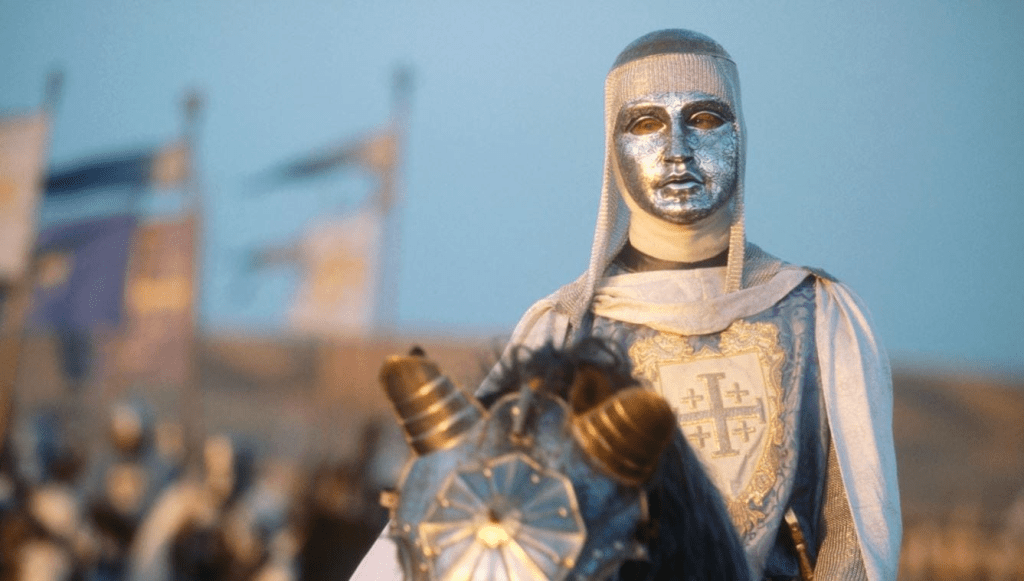

Continue readingFilm Favorites: Kingdom of Heaven (Director’s Cut)

It is embarrassing how much better Kingdom of Heaven is than the trivial, banal Gladiator, the film that did more than anything to kickstart the historic epic cinema trend at the turn of the 21st century and ensure director Ridley Scott financial solvency for eternity. I would only be being kind of hurtful if I were to say that this is the only one of Scott’s 21st century efforts that remembers that films think, rather than only represent things, visually. Scott works with real images in Kingdom of Heaven, visions that reward patient viewing, that express ideas that aren’t always fully worked out in a screenplay, that demand an attentiveness to conflict and polyphony on the screen, reminders of tension and multiplicity in real life. The man’s historical epics haven’t all been worthless. The Last Duel is at times amusingly rambunctious, raffishly brutal in its deconstruction of male idioms of medieval prowess. Napoleon is an ironist’s camp taxidermy exhibit of dead history, a complete evacuation of heroic power played as impudent impotence. But these are also misshapen things, and the kernels of value in them are often more intermittent amusements than the full-throated, painterly attention Kingdom of Heaven brings to a world that hasn’t changed as much as we’d hope. “Historical epics transmuting past idioms into timely political themes” is close to the least interesting film genre in the world to me, but I admired the combination of Old Hollywood earnestness and austere modern chilliness here, the David Lean-esque belief in the hope that well-observed compositions by observant and curious people can aspire to world historical importance and that, if they do fail, even because of their failures, they might mean something to the world.

I also admire how thoroughly this film manages to be both inspiring and deflating, often at the same time. This is a Hollywood blockbuster in which the final battle is a futile, grueling war of attrition, a vicious and unholy slog in which humans are physically saved, but not necessarily spiritually absolved, by an act of humility rather than might. Kingdom of Heaven is also a Hollywood blockbuster with an awareness of political economy, a genuine appreciation for the limits, but also the necessity, of human agency within impossibly wide systems of control and imperial conflict. There’s a fantastic sense of humans making their own future in a world not under conditions of their choosing, finding their way through a murk of conflict and confronting the forces of history that thrum far beyond their capacity to grasp them. Kingdom of Heaven manages to mark the characters as circumstantial antagonists in a tragic world, saved from mutual destruction by an act of strength through compromise and negotiation.

Continue readingMidnight Screenings: The Vampire Moth

There’s a proto-Giallo mischievousness to The Vampire Moth’s overstuffed story, an ever-cascading sense that this amounts to more and less than is on display, that the limits of logic are beside themselves, hopelessly unable to explain what we’re confronted with. The narrative implodes and folds in on itself, hurtling by with a feverish, feral brutality that is disarming in its disinterest in narrative closure. Written along with Hideo Oguni, and Dai Nishijima, director Nobuo Nakagawa’s The Vampire Moth is mostly a tatters from the beginning. In relation to post-war Japan, it feels mutational, like a nation growing quickly and in ways it hadn’t anticipated, organically following lines of inquiry that were not expected of it, a proliferating madness that the tidy rules of narrative cinema cannot contain.

Continue readingMidnight Screenings: The Invisible Man Appears

Most pre-Gojira Japanese science fiction cinema, even if it isn’t the no-man’s-land its reputation suggests, isn’t exactly self-conscious art. Its texture is blunt and suggestively playful, grimy and loaded with pulp. While Ishiro Honda’s apocalyptic Gojira unleashes an antediluvian earth resurrected by modernity’s godlike attempt to subject reality to what Martin Heidegger called “standing reserve,” and his later Matango evokes a world in which humanity was mutating in multiple directions, Nobuo Adachi’s The Invisible Man Appears doesn’t initially seem to have quite so much on its mind.

Yet Adachi’s film explores the entanglement of control and curiosity as shifting sand in a world where the possibilities, and perils, of the modern world seem both omnipresent and evaporative. In this tight potboiler, Dr. Kenzo Nakagato (Ryunosuke Tsukigata) tasks his two proteges, Shunji Kurokawa (Kanji Koshiba) and Daijiro Natsukawa (Kysouke Segi), with the development of an invisibility serum, offering his niece Ryuko Mizuki (Takiko Mizunoe) to the victor. Success in post-war Japan is a cut-throat intermarriage of private and public, in which personal ambition on all fronts is tethered to national and corporate well-being in a psychologically bruised and physically devastated ex-empire.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Hollow Man

The thing about Hollow Man is how trivial it is. I’m not the first to make that point, and I won’t be the last. This is an irrepressibly small-scale film for a Hollywood A-list director. Admittedly, Paul Verhoeven had been shunned by Hollywood with Showgirls and forgotten with Starship Troopers, but one senses this was less because the machine grew hip to his viciousness than because audiences hadn’t. They confronted these texts as incompetent films rather than self-conscious visions of Hollywood’s grotesqueness. With Hollow Man, it’s hard to blame the public for being ungenerous. It’s initially difficult to detect any critique altogether. It feels like this infamous self-hating Hollywood conspirator has finally been brought to his knees, forced to play along, as though he had lost any appetite for drawing blood. The American violence(s) explored by Robocop and Starship Troopers are forms of national fascism couched in ideological projects and delusory visions of a better world. Hollow Man is entirely devoid of any such romanticism, any grandness of vision, any sense that any of this amounts to anything. How does a film critique visions of American efficiency and brutality couched in aspirational opulence and moral zealotry when the film, itself, is so openly limited, so business-like, so blandly functional? There’s just so astonishingly little here.

Yet Hollow Man is major vision because it occupies such a minor key. I would submit that its viciously un-visionary nature is core to its vision of mercenary corporate cinema. Paul Verhoeven’s final English language Hollywood film is not arbitrarily banal but self-consciously inconsequential, a mercenary shiv to Hollywood’s gut from a double-crossing hired goon. Its vehemently local texture is the point. The aspirations and delusions of scientist Sebastian Crane (Kevin Bacon) are distinctly post-modern. His desire is not to control the world but to inhabit it, to fulfill himself more efficiently, to unlock his own personal capacity. Once he allows himself to be injected with the invisibility serum he has been developing, he has no interest in marketing this to the American military-industrial complex as a weapon to expand American hegemony. He just wants to become a more efficient killing machine all his own, to get off on his own competence, his own ability to manipulate sheer matter, light and shadow, to his own effects.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Sleepwalkers

That 1992’s Sleepwalkers was the first film Stephen King wrote directly for the screen is both a promise and an enigma. The idea suggests an unadulterated slab of Stephen King, the pure, uncut thing, untempered by the guiding hand of a translator. Watching the film, though, I can’t say I have any idea of what King thinks cinema is, or what its relationship to the written word is supposed to be. Sleepwalkers is quite a bedeviling monstrosity itself, actually. On one hand, it feels like a shredded expanse, the forced tightening of a larger, deeper, book-length text, the kind of thing that people refer to as the result of badly adapting an “unfilmable novel.” On the other hand, it feels equally like the product of King in the full grips of his drug-infused mania, badly grasping at half-finished ideas before they fade into murky nothingness.

In a literal sense, this film is neither of these. He was sober when he wrote it, and it was not, apparently, based on a larger text. But it feels like both. There are both too many and no ideas within it. It feels both overworked and entirely unfinished. It suggests the offspring of a man in the apparent full command of his own artistic invention who nonetheless doesn’t understand the core of what he has produced. It is a film whose genesis is as opaque as its final state. This is, charitably speaking, not a fully fleshed-out storyline. For all the flesh that gets ripped, shredded, broken, serrated, and corn-cobbed (read on), there’s very little meat on the film’s bones. It has the patina of a man who isn’t quite remembering why he has released this into the world, or where he wants this to go. The film accretes in, and is best remembered in, a fog.

Continue readingMidnight Screenings: Godmonster of Indian Flats

Godmonster of Indian Flats is like its titular creature in more ways than one. It shares its unruly, mercurial nature, its frustrated friction. It comes out of nowhere, from the abyss of an American id, or from some dim region of consciousness. And, above all, it has our souls on its conscience, the weight of the world impressing upon it. This is an alien being, a wonderful cinematic monstrosity that looks and sounds like nothing else, that feels like nothing else, and that was bequeathed to us, lost children in need of salvation, at the twilight of one period of American growth to teach us the error of our ways and offer, in the ugly, beautiful, grotesque, revolting fact of cinema, a shock that might help us see through the darkness, to see our darkness. In spite of it all, the film says, art, with all its misshapen curiosity and lumpy monstrosity, remains.

But saving us, the film posits, may mean destroying us. Godmonster of Indian Flats projects no beautiful harmony with the earth, no romantic image of art as a channel for grace. It is angry with us, a forgotten creature born unto this earth to witness our failings and prey that we might do better. It is an impossible creature of a film, a truly mad object, the prodigal creation of a nation and the scion of a mad scientist of an artist trying his hand at cinema. Writer-director Frederic Hobbs, was by day a wild bricoleur stitching solar energy and nomadic errantry and mid-century ideas about ecology and technology into something called Art Eco, one of those micro-artistic mid-century forms that resonated with a constellation of ‘60s modes, from the ever-curious, ever-deflationary termite art of Manny Farber to the more purely explosive tornadoes of internal energy produced by Jackson Pollock to the anti-technocratic romanticism of Frank Herbert’s Dune to the collective eulogy for a myopic world that was Buckminster Fuller’s Spaceship Earth. All of these frameworks, mechanisms of social critique and machine-work for a more humane world, invite us to rethink our relation to the rhythms of the cosmos, to expend less energy, or expend the right energy, to appreciate the irreducibly uncertain nature of reality and the horizontality of our diffuse formations and strange interconnections with one another.

Hobbs’s paintings celebrated this sensibility. His film, however, seems much less sure of our worthiness for salvation. We begin with a spirited journey to the margins of the nation, a group of youths on the path to adventure, “lighting out” to the territories, as they used to say. Cut to them pushing in on the camera, like a zombified parade of the damned, soon driving to nowhere, on the edge of an abyss. Perambulating into an uncertain future, this is the American road trip not as a long night of the soul but a night of the living dead. Promising a bounty of possibility, this Nevada-set film only offers a parched desert permafrost, a harbinger of a national thaw.

Continue reading