What does it mean to watch a murder? What does it mean to meditate on the cause of a murder? What does it mean to plan one? What does it mean to watch one being planned? To what extent are these four things different, and to what extent are they the same? “We’re just not very skillful at that sort of thing,” the film reminds us, and demonstrates, and the statement might apply to all of the above. Even when we think we’ve got a bead on what will happen to Edward G. Robinson’s Professor Richard Wanley, or what bit of evidence will or will not convict him, we keep wondering what it even means to judge someone, or to find someone guilty, or whether we can or should rely on any evidence given how easily each agentive act is contaminated by context, each exhibit for the prosecution claimed in part by chance. The ease with which the two protagonists find themselves more prepared than they expected to cover up a death and facilitate a murder, and the methodical way they begin to calculate their own moral slippage, is quietly penetrating. When the lights go up and the machinations of fate are apparently reversed in the film’s final minute, the grim realization is not that this was all an unfathomable dream but that the membrane separating determinism from contingency, demarcating sudden relief from a nightmare of existential guilt, is only molecule-thin.

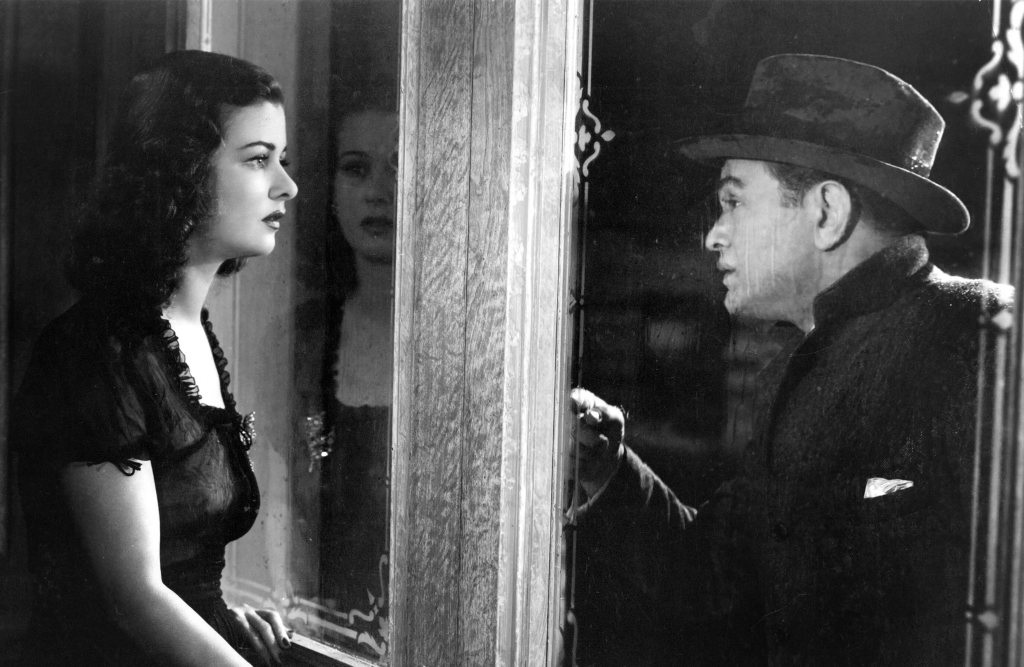

If you’re paying attention, this finale is also less of a sudden twist than a final admission of the film’s much earlier transfer from one imaginative plane to another. When Richard encounters Alice Reed (Joan Bennett) for the first time, the suddenly abstract visuals transpose the text to a transparently interior plane, moving him, and us, to a completely existential space where a thought can become a cataclysm, and a figment we might otherwise avoid becomes a new frame of reference. A late-night drink, where the two commiserating souls are both shrouded and illuminated by halos of light, announce their mutual curiosity and potential capacity for darkness. When she calls him back later that night, having accidentally killed a mafia man she isn’t quite a moll to, he promises to help her remove the body, knowing full well that the evidence will increasingly point to a mutual act of intentional and premeditated murder.

This film is, you can tell from everything I’ve already said, an excursion into the dark side, but it tellingly doesn’t really choose to produce an argument so much as engage an atmosphere. The film is not taking steps to mount a case but amassing potential evidence for many arguments, claims for simultaneous innocence and guilt and the fundamental contingency between them. The “femme fatale” here isn’t any more or less ambiguous than the rest of us, and she is no more or less complicit or willing to entertain her capacity for violence than Richard, or, presumably, us.

Robinson or Bennet, for that matter, are amazing in this. The ambling and somewhat aloof way Robinson walks to the phone to call the police, aware of his comforting resignation to the status quo and neither willing to acknowledge nor to truly challenge it, is deeply perceptive and quietly devastating. Bennett, meanwhile, is breathtaking, her voice absent any ego, her face capable of solidifying into a rock of sober dejection and dogged physical perseverance. When she backs up like a piece of furniture etched into a room she doesn’t even understand, she isn’t a femme fatale because she has given in to modernity’s pressure but because we suspect that we would.

For director Fritz Lang, one of the masters of deconstructing cinematic mastery, the contours of control and the limits of personal agency in the labyrinthine infrastructure of a spiraling modernity remained a perennial concern. His American films, which remain a cinematic after-thought to his towering German texts in the popular cinematic consciousness, are really variations on his perennial themes that expose the shifts in popular consciousness and the nature of power in the modern world. His American texts turned away from questions of elite sovereignty and toward the quotidian minutiae of people contorted into channels of fate they didn’t anticipate, summoning capacities they couldn’t even imagine. These are not omnipotent masters but fallible and entirely banal humans circling through life. Violence, its pull and propensity, seems fully beyond representation here, no longer localizable to a Mabuse or a Rotwang, no longer indexable via cinema’s ability to leap across time and space to tether causality together through violent dominion. Woman in the Window, fully immersed in mid-century film noir – a term which this very film was instrumental in the development of – sketches an architecture of ambivalence, an equivocal world not only of clandestine control but dormant psychological responses.

Who, or what, is the self in this unstable modernity, an addled and equivocal space in which we are all potentially criminals, in which we are all so easily not “ourselves”? Motifs of self-examination abound, a woman looking on at her own complicity in a mirror and a man looking at his decorous lifestyle organized in books. These are people not reckoning with external modes of manipulation but decidedly internal mechanisms of control, the depths of a more personal worry. Is Richard’s friend (Raymond Massey), a detective investigating the case, knowingly circumspect, or is he simply doing his job? Is Richard giving away slips of information, or is he really just making conversation? When Richard and Alice connivingly accept the killing the dead man’s reptilian bodyguard (Dan Duryea), who enters late-stage with enough oily, indirect charisma to make the screen break out in hives, are they negotiating a tragically unresolvable conundrum or are they announcing themselves as willing conspirators in the moral abyss of human existence?

Lang’s film engages the darker textures of self-renewal. Richard’s midnight trek to dispose of the body in the forested outskirts of New York (rendered as a fringe of sanity by cinematographer Milton Krasner) suggests the opposite of Stanley Cavell’s magical space of Connecticut, which here is an unfamiliar Gothic forest practically made to house a corpse with a horrid rictus grin. Once we enter this world, we see every wire-cut, every shoe mark, every second forward, as evidence for a hypothetical prosecution that doesn’t yet exist, or as potential exoneration for something he hasn’t done. Everything that confirms Richard’s guilt also deflates it. Everything that reignites him also disfigures him.

In this ambiguity, it is cinema. The film makes an extraordinarily obvious case that he is a culprit and that he won’t really be considered one because of his respectability and that it only makes sense to us that he did it because we’re watching a movie with him as the protagonist. We really wouldn’t assume anything notorious of him if the camera hadn’t winnowed our gaze down to him and focused us on the question of guilt. Cinema, the film proposes, indicts the world, returns us, as Walter Benjamin wrote of photography, to the scene of the crime, suggesting that everything could be a crime, but that the crime goes far beyond the individual actor at the tail end of the act. What even does guilt mean in this world? Woman in the Window is deliciously circumstantial, somehow both razor-tight and ragged-loose. It moves with bullet-like precision and yet somehow produces so many intangibles that both do and do not matter. Police officers materialize out of nowhere and then evaporate into a haze of anxiety and liminality just as quickly. This is the realm of cinematic life, in which every item is expanded and accentuated and yet every meaning is also questioned and rendered contingent. The totemizing of an image, Lang offers, is not tantamount to lacquering it in inflated meaning or artificial purpose but, instead, acknowledging its fundamental iridescence.

Score: 9/10