People have been sleeping on this one, and Die Hard with a Vengeance is a film precisely about not falling asleep on the job. It’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the rare action movie that is interested not in demonstrating what it can show us but how it can attune us to the act of showing. So many times throughout this film, the camera gracefully and sinuously pivots around a character’s face and then zooms inward to the object of a dawning realization, either across the street or across the city, a recognition that consistently signals something is afoot but seldom explains what, exactly, is going on. Director John McTiernan repeats this maneuver so often throughout Die Hard with a Vengeance that it becomes a nervous tic, tweaking the text into a series of variations on a theme, a tilted, post-modern blockbuster for a tumultuous world.

Die Hard with a Vengeance is a highly-strung text, a film for the masses with the movements of the masses on its mind. For the series protagonist’s first film back in New York, John McClane’s ostensible home, the film dedicates itself to making us feel like a stranger, casting us adrift, unanchored, through transportations, transmutations, and teleportations. Die Hard with a Vengeance feels like the anti-Die Hard, and no surprise. Star Bruce Willis only agreed to return if the film zigged when the earlier texts zagged. Rather than the first film, a vicious bottleneck, Die Hard with a Vengeance splays outward, a murderous carousel rushing us back and forth while also tacitly and gravely intimating that it’s having maniacal fun with us. (Speaking of which, this film walked so that Fincher’s The Game could run.) An episode at Yankee Stadium is just the film giving the characters and the audience the runaround, showing us a New York City landmark merely because what would McClane’s return to NYC be without it? This is a rich, relational film about what it means to get across a city like this, and what it means to survive through it.

Can McClane get through it, and at what cost, and to what new world? “I’m a soldier, not a monster,” remarks the cool, Machiavellian Simon (Jeremy Irons) who has it in for McClane for undisclosed reasons, and is presently dragging him all around the city on a wild goose chase. This is his world, the film suggests, a labyrinth of lines and dots and comers and goers manipulated, Mabuse-like, by an embodiment of late modernity’s casual cruelty. Simon is a smooth and skillful operator who is both McClane’s antithesis, in his professional dispassion, and his double, in his capacity for confusing and befuddling others and propensity to merge the social and the personal in ways that ask us to question which he is really fighting for. More than in any of the other films, there’s a sense that McClane is both a good man and an asshole (in the latter sense, he’s very much like Hans Gruber before him), that he means well but that his claims about intentional compassion may just be a smoke-screen for a compulsion to get on bad guys’ nerves.

McTiernan, a master visualist and theorist of vision, does real dirty work with the film’s view of McClane, to impressively thorny ends. At one point, McClane, our resident heroic Irish flatfoot cop, plays an Irish flatfoot construction worker, glimpsed by a perpetrator only through a rearview mirror, before shooting a man in the back. Earlier, a bank invasion is shot as a mock inversion of American militarism, a parody of the nation’s martial politics and America’s fetish for espionage. A key kill in this sequence is visualized on a camera feed, a frightened man too busy looking forward at what he assumes is his opponent to appreciate the killer stalking his periphery. Without a word being spoken, the film informs us that McClane and our villains share certain similarities. They both inhabit a world where images are mutable and truth can be contorted. They’re both willing to play dirty to get where they need to be. The film gets here visually, demanding that we connect the dots in a disconnected world. No “we’re not so different, you and I” to literalize the theme from Jonathan Hensleigh’s script, a tetchy mosaic of city-scouring escapades in which getting from one end of the street to the other is both a walk in the park and a mountain to climb.

Compare this to the fourth film in the series, Live Free or Die Hard, which is even more explicitly about the infrared means by which control can be mobilized against itself, in which a social system can be rigged and tripped and wound around itself. That film requires a much more significant narrative infrastructure and far more conceptual circuitry to make that point, but it has no visual ideas for what these new modes of power represent in modern society, or how they might interact with a camera that moves and deceives, that sees and lies. We see many camera feeds in that 2007 text about the Bush-era security state, but there’s no sense that they meaningfully interact with the film camera at all. Die Hard with a Vengeance, however, has only one closed-circuit camera, and the scene in which it very briefly appears is a whole meditation on the human capacity to be fooled by technological fakery, to expect a forward assault and not recognize a sideways flank. Fresh off of 1993’s Last Action Hero, John McTiernan has directed a film in Die Hard with a Vengeance that is earnestly and mischievously interested in the limits of our perception of action movies, all the more so because, unlike Last Action Hero, this one so tightly wears the skin of its object of critique, so refuses to blink for us.

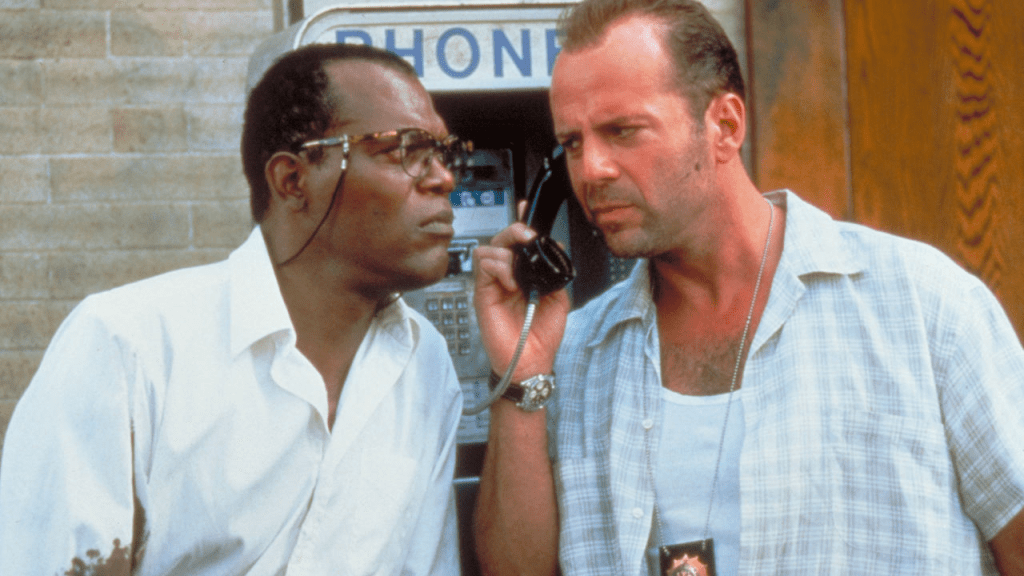

At times, Vengeance bites off more than it can chew. Its racial politics are squarely within the “racial consensus” school, in which the problem with America is fundamentally individual, the solution fundamentally a matter of compassion and friendship. Systemic power, the sense of infrastructure that the film so thoughtfully visualizes elsewhere, has no place in its vision of America’s color line. Still, even here, there are fumes of thoughtfulness. Samuel Jackson, playing McClane’s partner in crime Zeus, is too supple and volcanic to not layer recognition of systemic racial inequality into the film, and it occasionally works as his partner in crime. In a key scene, when he needs to answer a phone to stop a bomb can’t because of a police officer’s obvious assumptions about his intent, the film begins to reckon with what it otherwise refuses.

Flaws aside, McTiernan’s film is extremely conspicuous and much too worked-out to be avoided. This is the man who directed Predator more than Die Hard, a guy genuinely interested in forces operating outside our field of view, in strange presences that are not the expected strange presences that we too-easily demonize, in conceptions of camaraderie that are more fragile than natural, in heroes operating out of their league, facing a threat that is ethereal and opaque, that may not even exist, in environments that we are less at home in than we need them to be. This would be vulgar auteurism if McTiernan weren’t so respected a director, working at the top of his talents telescoping a vision of the city as a circus and a colony, a muscle and an impediment, narrowing and widening at once and then circling back around to stab us in the back.

Score: 8.5/10