It is embarrassing how much better Kingdom of Heaven is than the trivial, banal Gladiator, the film that did more than anything to kickstart the historic epic cinema trend at the turn of the 21st century and ensure director Ridley Scott financial solvency for eternity. I would only be being kind of hurtful if I were to say that this is the only one of Scott’s 21st century efforts that remembers that films think, rather than only represent things, visually. Scott works with real images in Kingdom of Heaven, visions that reward patient viewing, that express ideas that aren’t always fully worked out in a screenplay, that demand an attentiveness to conflict and polyphony on the screen, reminders of tension and multiplicity in real life. The man’s historical epics haven’t all been worthless. The Last Duel is at times amusingly rambunctious, raffishly brutal in its deconstruction of male idioms of medieval prowess. Napoleon is an ironist’s camp taxidermy exhibit of dead history, a complete evacuation of heroic power played as impudent impotence. But these are also misshapen things, and the kernels of value in them are often more intermittent amusements than the full-throated, painterly attention Kingdom of Heaven brings to a world that hasn’t changed as much as we’d hope. “Historical epics transmuting past idioms into timely political themes” is close to the least interesting film genre in the world to me, but I admired the combination of Old Hollywood earnestness and austere modern chilliness here, the David Lean-esque belief in the hope that well-observed compositions by observant and curious people can aspire to world historical importance and that, if they do fail, even because of their failures, they might mean something to the world.

I also admire how thoroughly this film manages to be both inspiring and deflating, often at the same time. This is a Hollywood blockbuster in which the final battle is a futile, grueling war of attrition, a vicious and unholy slog in which humans are physically saved, but not necessarily spiritually absolved, by an act of humility rather than might. Kingdom of Heaven is also a Hollywood blockbuster with an awareness of political economy, a genuine appreciation for the limits, but also the necessity, of human agency within impossibly wide systems of control and imperial conflict. There’s a fantastic sense of humans making their own future in a world not under conditions of their choosing, finding their way through a murk of conflict and confronting the forces of history that thrum far beyond their capacity to grasp them. Kingdom of Heaven manages to mark the characters as circumstantial antagonists in a tragic world, saved from mutual destruction by an act of strength through compromise and negotiation.

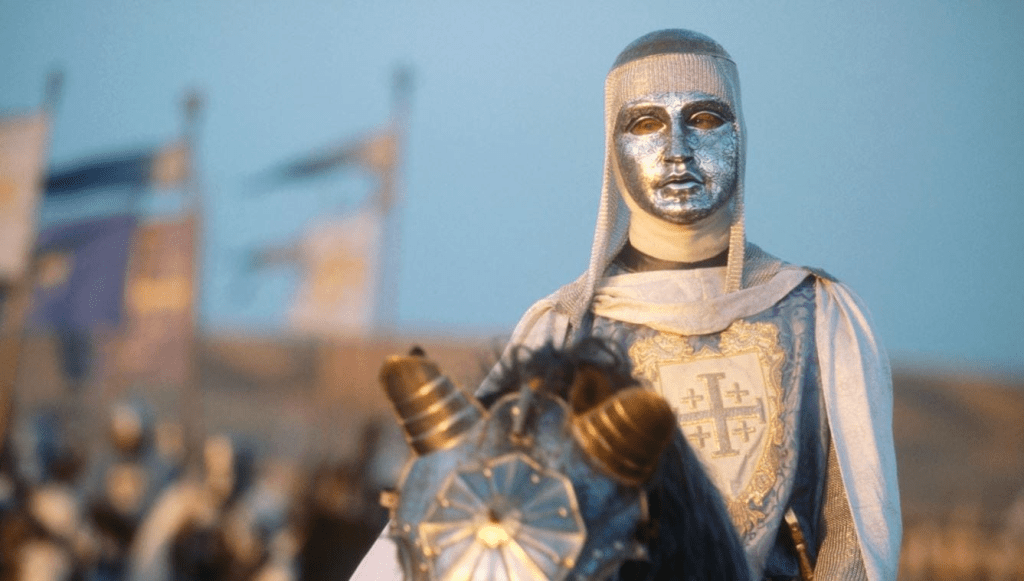

This is only in the director’s cut, mind you. Only here do the circles square and the fringes still remain productively confused, perhaps unanswerable. Only here do we understand the magisterial gloom of Edward Norton’s romantic-tragic prophet King Baldwin IV, his pitiful and pitiless attempt to achieve wounded grace in a world of imposing edifices and readymade icons, something he recognizes he is becoming. Only here do we intuit his sister Sybilla’s (Eva Green) tragic hope to secure her son’s already-compromised position as his replacement, only to realize that he is doomed to the same fate as his uncle. Lost in a crestfallen, self-hating miasma, impotent power and political myopia, her own sense of mortality finally becomes humbling and humanizing at the film’s very end, transforming her final decision to treat wounded flesh into an act of personal penance, an attempt to break, while also recognizing, a cycle of historical recursion.

There’s plenty more to dwell on here. The way John Mathieson’s camera frames the sand as a putrid malaise and the mask on Norton’s horribly self-aware golem with a soul-worn glint. Or the fetid demise of a caravan dismally dwarfed by circling crows. Or the fact that the battles are sad, despondent things, with the final image of the final battle a pitiful mass of flesh and indistinguishable bodies struggling in ignoble abjection, locked into a grotesque mass which the film implies achieves nothing. Or a child realizing that something is fundamentally wrong with him and not really knowing how to grapple with this. Many of the most telling incidents are unstressed details, like a dagger that is also a cross stabbed into the eye-slit of a man who can only see through a limitation himself, his cross-mask an armor of protection that is in fact a mark of myopia, a narrow corridor of vision that is also a sign of weakness. Contrast this with the camera’s circle around Balian at the beginning of that fight, capturing him in an oasis of penitent, solitary hope as he grapples with his own values, observing the world as he is lost in a massive pop epic of phenomenal proportions, recognizing that grace is both midwifed by grandiosity and completely imperiled by it. Here, the film clarifies its debt to Lawrence of Arabia, resonating with the modern sensibility of characters who know they are trapped in a history beyond their own making, trying to figure out what to do with it, and what their relevance to an improbable future might be.

Only in the final duel does the film offer an answer, providing Balian with two visions of salvation. Lost in the orgiastic maw and demonic-pluralistic colors of clothing billowing around him as his final swordfight plays out in delirious, vengeful abstraction, Balian is momentarily prey to a masculine retributive violence that is vivifying but ultimately engulfing. In Balian’s solution, however, he finds a way not to defeat his opponent but to morally condemn the institution he represents.

The film has its problems. It’ll be no surprise that Bloom is not very good, and I can’t quite convince myself that there’s a Kubrickian, self-critical gloss on the film’s use of him, treating him as a banal icon whose successes are hollow triumphs in the dredged-out morass of humanity. That’s a viable reading in parts – he is a semi-passive man fulfilling an imposed historical archetype, and the film is about how becoming a knight is more often than not a path to evacuating you of your humanity – but I don’t quite think that the director of Gladiator has it in him to be that deflationary. Balian is still too sympathetic for his own good, which, more than anything, keeps them from achieving Arabia-levels of angry, self-critical grandeur. The film simply believes too much in his self-emancipation, even when it is reckoning with the limits of that very process. Still, the final “nothing … everything” is sold by Ghassan Massoud’s noble Saladin, the ostensible villain who is really an antagonist of historical circumstance, as an ironist’s vision of a too-aware history in which no one can really transcend. Saladin recognizes this as a world in which the historical sand beneath our feet is never not trying to swallow us whole, and Balian can only choose the ambivalent possibility of itinerant grace in the film’s final moments.

Scott earns that awareness in Kingdom of Heaven. He isn’t, to my mind, an obvious auteur, and his scripts get the better of him more often than not. But he is a thoughtful and considerate journeyman, an artist struggling to remain attentive to the world around him without announcing his masterful dominion over it, Elephant-art style, or, on the other, submerging into the cracks to the point of perspective-less functionality. Balian is a man struggling to balance popular appeal with personal integrity with humanist openness, and there’s a touch of this tension to Scott’s approach to filmmaking. Balian’s enemies are zealots, demanding devotional ardor. He develops a perseverance through observation, and he quietly concludes the film by casting his lot with the unsettled terrain of humanity between the obelisks of machinery and ideology, something Scott is not always able to do, but which he does here. When Balian returns home finally, he is only “the blacksmith,” choosing no knighthood and no land, accepting a kind of hope in which inheriting a place is only a precondition for an adventure into the unknown. That’s the film. It saves us from nothing, offers no lifeline other than the fallible and tenuous benediction of its images, the power of art as a submission to the world that hopes we might see that world anew.

Score: 10/10