Compared to many of Luis Buñuel’s earlier and later films, Belle de Jour is veritably chaste. None of the high-concept chicanery of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, nor the perverse, assaultive energy – the film camera as weapon – of Un Chien Andalou, nor the bracingly deconstructive arbitrariness of The Exterminating Angel. Buñuel, perhaps aiming for a mainstream hit, keeps the texture tight and controlled, even neutral, in his biggest crossover hit. Buñuel was incapable of not being mischievous though. Belle de Jour, with its steely screenplay by Jean-Claude Carriere (based on the novel of the same name by Joseph Kessel), turns its own milquetoast limitations into a paradoxical stylistic coup, turns its lukewarm nature into ice-cold venom. The film’s occasional flirtations with fantasies of sexual ravishment feel like explosions of the repressed unleashing itself from the film’s cloister. They don’t structure the film but work like structuring absences for most of the text, things that must be kept off-screen for the narrative to function, pulsations that must be kept in check for society to keep afloat. Belle de Jour suggests that its own existence as mainstream narrative is a form of waking death.

Or perhaps the explosive visions aren’t so explosive after all. Perhaps they’re actually just as anodyne and chilly and washed-out as the rest of the film, and perhaps that’s the point. The text begins with a mock classicist sketch, in which the main couple ride through an autumnal setting in Victorian garb, dressed up in prim and proper bonafides. Suddenly, the moment morphs into a decidedly mechanical account of sexual frustration, an emergent erotic violence that feels like clockwork more than animal id. So much so that the blasé narration intimating that this is some sort of dream or fantasy feels less invasive than natural to the rhythms of the dream. The energy we’re supposed to feel, bare reality erupting through its Victorian cage, feels all the more artificial, all the more part of this cage. This desire to return to history as an escape from the present seems to fit so cleanly into a distinctly modern worldview. It implies that bourgeois modernity, so easily sliding into this repressed history’s fold, is itself part of the frustrated desire that the dream imagines. The 20th century, like the 18th, is a dream that is as repressive as it is liberatory for the film. The banality of it all channels into Catherine Deneuve’s icy, fiendishly interiorized performance, and it renders the bourgeois trappings of modern France decidedly, diabolically artificial, desperately in need of the shock that would come the ensuing calendar year.

Deneuve plays Séverine Serizy, a woman who is unable to summon any sexual interest for her ostensibly perfect husband Pierre Serizy (Jean Sorel). Upon learning of a friend who has taken up employment as a high-class member of the oldest profession, Séverine tries her hand at a career that might satiate a desire the film recognizes is not only sexual but social. She wants to be something other than a wife. Coined “Belle de Jour,” she doesn’t take easily to the job, and the film is attentive to her own ambivalence, but its offers seem appealing enough to achieve sentience, alive enough to make their way into, and rekindle, her love life with Pierre. Eventually, she is courted by the younger, rakish, alienated Marcel (Pierre Clementi), who feels like a parody of cinema’s stereotypes of wayward youth culture in his disaffected demeanor and anticipates Bond’s Jaws in his mostly metallic front teeth. Buñuel’s film thus looks back on mid-century bourgeois resistance, to the quiet death of subjugation to the home, and forward to the zealous burnout of ‘70s ennui, where resistance to the status quo was ultimately reduced to a series of privatized fantasies of personal becoming, fantasies the film recognizes Séverine to be as guilty of as anyone else.

Admittedly, while she won’t admit to them, her fantasies do sometimes feel organic in a way that none of the men’s delusions seem to. Theirs are comic absurdities that stretch to the point of abstraction. A prestigious gynecologist imagines himself as a buffoonish servant to a female master while nonetheless surreptitiously wielding the on-off switch for a fantasy that is necessarily his. Another man conjures his daughter’s sexually-charged funeral. An Asian businessman shows up with a strange box that seems to affirm and then to mock orientalism with its sheer arbitrariness. He seems weird because he’s supposed to be weird. His role demands it, much as Marcel, whose frustration does little to actually create a “conflict” in the traditional narrative sense, must, by virtue of his type, be a loner prone to anger and the needs of immediate gratification.

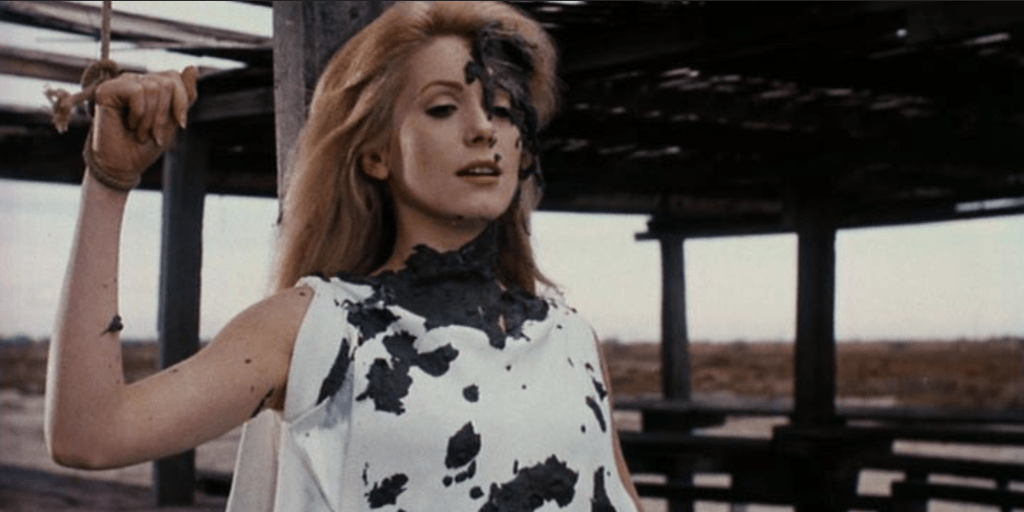

Belle’s fantasies, meanwhile, are hilarious implosions of male control and extensions of her own instability in being subjected to mock punishment by the men around her. One fantasy positions Pierre and their friend Henri (Michel Piccoli), who told Séverine about the brothel initially, as faux-frontiersmen. Living out a simulacrum of pioneer life, they suddenly shift to shoveling copious amounts of mud on Séverine as she looks on with inviting dispassion. Their identity is predicated on abusing her, but the thing that sells the scene is the off-handed way in which they simply enact their identities, not as a passion-project but a performance of due masculine diligence as sterile as their daily affect at work. They are living out types as soul-destroying as Séverine’s life as a housewife. She derives a kind of joy in denying them pleasure, in feeding them their power and knowing that their interest in it is more structural than sensual, that they engage with her like it’s little more than their 3 o’clock. Her fantasy, it seems, is to recognize how dead they really are, even when living out an image of masculine life.

Her private life apart from the role of housewife, her fantasy, is also, nonetheless, a public role, as mistress, a participation in something that resembles civic society that is also a grotesque parody of the power relationships that condition that civic status. Her job is her way of participating in the give-take of the social economy, and the film’s way of confirming how hollow that economy can be when it demands women engage in further subjugation in order to feel a simulacrum of what it might mean to be free. Séverine never really escapes, perhaps because her own oppression has been interiorized. Her desire is to reveal the complications of this system by exploring it, but she doesn’t believe she can, or doesn’t want to, escape it. The organic energy of her dreams, that they feel so alive, is also part of the problem. They catalyze her to question society, perhaps, but also to fit more easily into it as it stands. We cannot be sure what would really make her happy, or what would save this society. Attentive to Séverine’s forbidding sense of self as well as the anarchic energies coursing within her, Deneuve is beautifully reclusive and iridescent. She radiates amorphous stillness without sacrificing her obvious resolve, never softening Séverine’s listlessness or selfishness, nor rationalizing or providing justification for her desires, which remain wisely opaque. These are sensual and sensational fringes of the mind feeling out the cracks of a society, not knives dissecting it.

Buñuel concludes by interweaving two apparently disparate worlds in an image that folds autumnal nature into sterile city, fantasy into reality. Producing something that initially looks like harmony, the film consummates itself, achieving its inner equilibrium, before it breaks again into a fragmented image of duality. The apparent blurring reveals itself as a congealing of society’s internal confusion, not an overcoming of it. Although he promises smooth consonance, a final similitude of reality and desire, Buñuel concludes with a refiltration of images, a final dissonance that first offers Séverine one form of real mastery and then, separately, grants her romantic fulfillment. The film’s conclusion offers a vision of Belle’s agency over a now inanimate husband and another of love achieved. It has promised us a melded world that, it suggests, cannot be. She can’t have both. It is too good to be true, and the possibility of both must be presented as a breakage of the film, one where the boundaries between dream and reality are so deeply entangled as to lose all meaning.

Score: 10/10

Insightful — and entertaining — analysis, but I feel I should point out that the film’s (and novel) actual title is “Belle *de* jour”.

LikeLike

uhhh … shows what I know … Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’ve all been through it… and in public yet. Cheers, Jake!

LikeLike