Woman in the Dunes is the story of matter’s murmur, how it promises and then profanes. An unnamed entomologist (Eji Okada) opens the film wandering the coastal desert dunes of a seemingly out-of-the-way corner of Japan, far from his daily life in the doldrums of Tokyo’s burgeoning modernity. For the entomologist, the dunes promise relief from the workaday banality of modern city life, promising challenges to pursue, forces to explore, submit to, and command. He hopes they will unsettle him, that the romantic pull of the sublime otherness of these forbidding desert dunes will sink into his soul, that they will bring him outside himself and thereby return him to himself after communing with the world. But the film slowly impresses on us that his quest is a dangerously abstract escapade, one that takes him away from modernity’s tensions rather than into their conundrums. The titular dunes, with their eerie, eons-long omnipresence, their mixture of grace and gloom, lay his solipsism bare, drowning his ego in forces he wants to both dwarf and that he wants to dwarf him. The titular dunes are iridescence embodied, warping any meaning imposed on them. Alternately confessional stall, open-air penitentiary, and vast abundance, they can stand for seemingly anything and thus, perhaps, afford nothing other than a cosmic trick. The dunes offer this man his soul renewed before holding a mirror up to his inner cravings that he would rather not see. Woman in the Dunes understands that the line between spiritual purgative – hope for cosmic salvation – and menacing infinity – adriftness in a void of your own making – is gossamer thin.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: August 2025

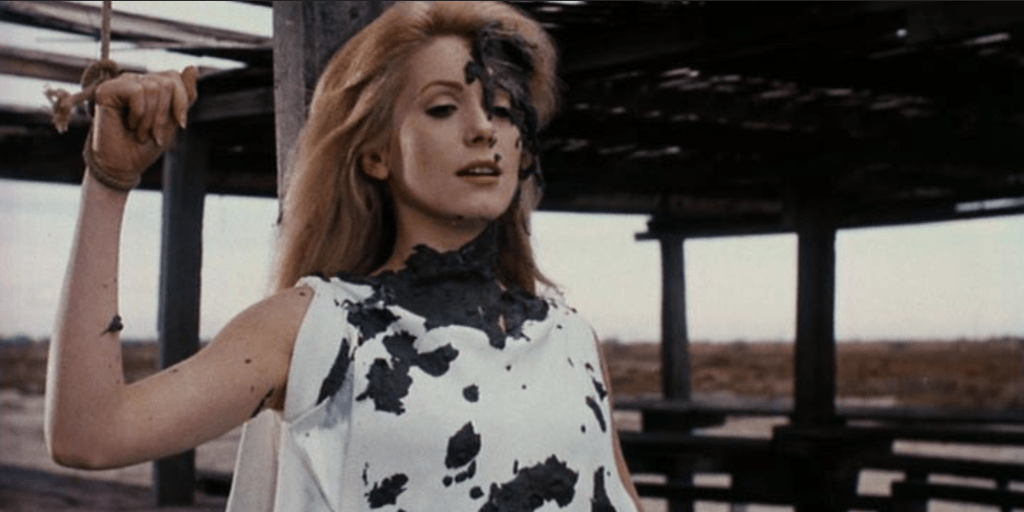

Film Favorites: Belle de Jour

Compared to many of Luis Buñuel’s earlier and later films, Belle de Jour is veritably chaste. None of the high-concept chicanery of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, nor the perverse, assaultive energy – the film camera as weapon – of Un Chien Andalou, nor the bracingly deconstructive arbitrariness of The Exterminating Angel. Buñuel, perhaps aiming for a mainstream hit, keeps the texture tight and controlled, even neutral, in his biggest crossover hit. Buñuel was incapable of not being mischievous though. Belle de Jour, with its steely screenplay by Jean-Claude Carriere (based on the novel of the same name by Joseph Kessel), turns its own milquetoast limitations into a paradoxical stylistic coup, turns its lukewarm nature into ice-cold venom. The film’s occasional flirtations with fantasies of sexual ravishment feel like explosions of the repressed unleashing itself from the film’s cloister. They don’t structure the film but work like structuring absences for most of the text, things that must be kept off-screen for the narrative to function, pulsations that must be kept in check for society to keep afloat. Belle de Jour suggests that its own existence as mainstream narrative is a form of waking death.

Or perhaps the explosive visions aren’t so explosive after all. Perhaps they’re actually just as anodyne and chilly and washed-out as the rest of the film, and perhaps that’s the point. The text begins with a mock classicist sketch, in which the main couple ride through an autumnal setting in Victorian garb, dressed up in prim and proper bonafides. Suddenly, the moment morphs into a decidedly mechanical account of sexual frustration, an emergent erotic violence that feels like clockwork more than animal id. So much so that the blasé narration intimating that this is some sort of dream or fantasy feels less invasive than natural to the rhythms of the dream. The energy we’re supposed to feel, bare reality erupting through its Victorian cage, feels all the more artificial, all the more part of this cage. This desire to return to history as an escape from the present seems to fit so cleanly into a distinctly modern worldview. It implies that bourgeois modernity, so easily sliding into this repressed history’s fold, is itself part of the frustrated desire that the dream imagines. The 20th century, like the 18th, is a dream that is as repressive as it is liberatory for the film. The banality of it all channels into Catherine Deneuve’s icy, fiendishly interiorized performance, and it renders the bourgeois trappings of modern France decidedly, diabolically artificial, desperately in need of the shock that would come the ensuing calendar year.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Matango

For many film viewers, Ishiro Honda’s legacy rests almost entirely on one film. More populist than the Japanese masters like Ozu or Mizoguchi, less frenetic and frazzled than, say, Seijun Suzuki, and more sober and sophisticated, and thus more chaste, than the exploitation pictures riding in his wake in the 1970s, his films, eminently corporate in their way, can be parsimonious in doling out satisfaction for auteurists looking for the trademark stamp of a recalcitrant, personal touch. Functionally, this means that his straight-and-narrow sensibilities sometimes flatten his oeuvre out for an audience who mostly remember his epochal 1954 celestial howl Gojira and forget that the man who unleashed that scathing, wounded critique on the world had a career lasting several decades. While his style was more streamlined than many other concurrent Japanese directors, Matango serves him well: it boils down his populist horror sensibilities to the bone, perhaps because it is about the streamlining of humanity into a smooth paste of consumerist pulp. While Gojira lets the blood run raw, demanding to be witnessed in all its sublime monstrousness, Matango cauterizes the wound, slowing things way down for examination. And then it picks at the scab. It simmers down the former’s cosmic canvas of international panic for a seven-person cast waywardly trapped on a forgotten island of the soul.

Released a decade after Gojira, Matango depicts a recovering Japan, or one that never actually bothered to ask what genuine recovery would mean. It begins with a newly resurgent, distinctly modern bourgeoisie, twenty years on from the war and, apparently, relatively untroubled by and weathered from the immediate shock of absolute destruction. Although we know, beforehand, who the designated “survivor” of this story is, there’s little sense in which psychology professor Kenji Murai (Akira Kubo) is a protagonist, other than being slightly more level-headed than the other characters, all of whom, finally, prove susceptible to the call of another life beyond the one humanity has made for itself. Each, in their way, is entirely amenable to the siren song of a scientific homogeneity that presents itself as a radical otherization but, in fact, simply marks the blasé hollowness they’ve already accepted as their daily livelihood.

Continue readingFilm Favorites: Testament of Orpheus

Few questions received such a pressing and recurrent tribunal in mid-century European intellectual culture as Theodor Adorno’s inquiry about whether there could be “poetry after Auschwitz.” For essayist, poet, and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, poetry may be all we have. The problem, both Adorno and Cocteau understand, is that poetry is complicit in cruelty, that feats of human imagination are entangled with the abstracting violence of mass destruction and the failure to acknowledge human reality. Art, Testament of Orpheus proposes, has a “a very poor memory for the future,” and it can be complicit in its own metastasizing as weapon and mechanism of power. Its dreams of a better world, the film well knows, all too easily become fantasies of control and justifications for destruction, means by which the poet’s will creates a new world prey to their sovereignty. In “repeatedly attempting to trespass to another world,” the poet is “besieged by crimes (they) have not committed,” by the potential violence of escaping the world, by the horrors done via technology attempting, like cinema, to conquer time itself. Art, the film posits, is an “innocence” that is nonetheless “capable … of all crimes.” Cocteau’s film begins as an inquiry into art and morphs into a testament to the necessity, in spite of everything, perhaps because of art’s very ability to do evil, to artistic transformation.

I’m quoting from the dialogue so much because Testament is a poet’s movie, the kind of robust and self-referential text a film theorist (as Cocteau was) would produce, particularly a theorist so eager to tinker around in a world where the “living are not alive, and the dead and not dead.” It can be a little self-serving, and Cocteau’s smirk – both his directorial elan and the knowing grin he dons on camera, as “the poet,” an iconographic variation on himself – tells us all we need to know about how aware of that self-service he is. The artist, try as they might, “always paints his own portrait.” But Testament of Orpheus turns egocentrism into ecology, the inward gaze into the relational soul. Cocteau is keen to invite us to participate in cinema’s own liminality, to join hand in hand with its own navel-gazing. Its vision of art is a “petrifying fountain of thought,” and if it petrifies like Medusa’s gaze, it also reminds us that witnessing that petrification via art is the only path we have to confront the world in all its complexity and emerge galvanized for further inquiry. One would be hard-pressed to find a more petrifying vision than Testament, so completely does it stop and restart the rhythms of the mind via a cinema of perpetual free-fall.

Continue readingFilm Favorites: Veronika Voss

One always gets the sense that Rainer Werner Fassbinder was entirely sincere in his affection for Douglas Sirk and mid-century Hollywood melodrama. His was a self-reflective cinema, but not a self-excoriating one. Melodrama, for him, is not just a manipulative fallacy or an ideological construct so much as a tragic mode of narrating the tensions between internal desire and external conditions. Fassbinder’s gaze, which seems to breach the prison of the skin and pull forth the evanescence of desire itself, seems genuinely descended from the expressionist tradition. His films aren’t deconstructions of his inspirations so much as meditations on them, ones that, because they actualize and then shatter the characters’ wildest fantasies and most disturbing dreams, expose the cracks in their hopes and articulate the jaggedness of their imaginations.

Veronika Voss was perhaps Fassbinder’s most obvious reflection on his cinematic origins, and that comes with enough baggage to risk turning the film into an obvious allegory of his love for classic cinema rather than a genuine interrogation of it. Veronika Voss is a relatively apparent variation on Sunset Boulevard: a titular former celebrity (played by Rosel Zech), desperate to reengage her career after the point where mainstream German cinema has cast her aside, increasingly confronts the limits of her drug addiction and the conflicting demands of an abusive doctor (Annemarie Duringer) who derives satisfaction from keeping Voss under her thumb. His final film released during his life time, the relative straightforwardness of Veronika Voss’s situation implies the consummatory quality of a director knowingly at the end of his time on earth, offering a final effigy for the inspirations that fueled him.

Yet this is no honorary replaying of an old standby, nor a mere post-modern ode to his fascinations. Veronika Voss is not Norma Desmond. Rather than a toxic statue striving to fully absorb Old Hollywood ghoulishness and exaggeration for her own malformed, abused ego, Voss is a drifting angel caught in modernity’s moonlight. Demond’s needs were gravitational, coaxing the entire film into her orbit. Voss’s are electromagnetic, loosely centering a field of particles, each character compromised by each other, everyone working a disruptive but also often empathetic malice upon each other as they harness one another for various ends. Fassbinder’s film isn’t the story of a lone, maddened, monomaniacal soul exerting force on others but a nebula in which everyone trying to fulfill their self-lacerating needs and hopes causes each other to come undone, in which individuals emit, radiate, and dissipate together for better or worse. Near the end of his career, perhaps because it sees him fading into the netherworld of cinematic afterlife, the liminal space where the dream factory goes to play afterhours, Veronika Voss feels like a ghostly transmission from another world, laying bare a dream Fassbinder has of artistic rapture – film fulfilling your dream life, allowing you to transcend into an artistic ether – that he can’t believe even as it lingers in his mind and shivers into his soul.

Continue reading