Early in Anthony Mann’s seriously neurotic and starkly severe Reign of Terror, a sinister hand excretes from the border of the frame and reaches up to choke the man we have thus far assumed to be our protagonist. The camera suggestively observes who we take to be our hero in a mirror’s gaze while an unknown assailant stabs the man in the back. Within a minute, this film not only reintroduces the man wielding this phantasmic appendage as our real hero but shatters the accepted vision of historical cinema that would believe in clear gazes and untroubled viewpoints to begin with. Both Orwellian and Wellesian, this is a historical anti-epic that entirely disfigures historical cinema’s own panoptic “epic-ness.” It erects an edifice of cramped people who can barely see where they’re going down the cloistered, blinkered hallway of history. If cinema often promise to reflect the past to us, Reign of Terror offers an ever-cracking mirror.

Poetically, this marks Reign of Terror as a hell of a text, not a milquetoast, straight-laced historical suit-and-tie but a full-on expressionist straight-jacket. Politically, it means that the film has little use for historical grandstanding, and that its politics can verge on drowning revolutionary potential – the hope of a genuinely better world – in a swamp of what passes for “complexity” but may simply be confusion. Released in 1949, Reign of Terror is a transparently fearful text. It is a Cold War casualty fully in line with the politics of the time. Its opinion is that revolution is often more foolhardy than not. It resonates with what Lionel Trilling would call the liberal imagination’s fear of dogma and its metaphysics of calibrated uncertainty, Isaiah Berlin’s appreciation of “negative liberty” as a bulwark against what he perceived to be the excesses of totalitarian solidity, and Hannah Arendt’s belief that the Soviet revolution was merely an extension of the French Revolution’s inevitable slide into dictatorial control. The film’s portrait of Maximilien Robespierre is as a self-important monomaniac exercising autocratic dominion, a God-like puppet-mater who calmly intones things like “I made the mob. They are my children, they won’t kill their own father.”

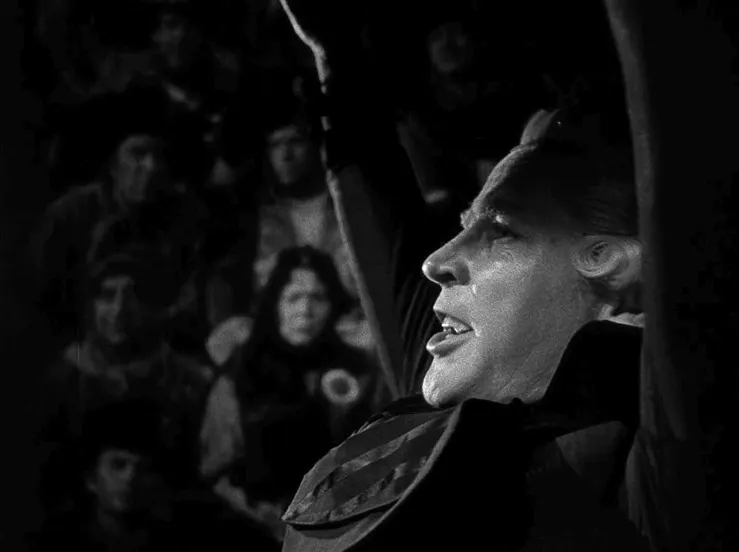

Yet Reign of Terror evidences a deliriously morbid, at-times nearly erotic fascination with death regardless. It is conservative, in the small-c sense, but Reign of Terror is also troubled and tormented in a way that is never less than fully fascinating. While the “history film,” in 1949 as it does now, promises an unceasing access, a panoptic gaze, Reign of Terror turns the limits of its micro-budget production into a boon to its imagination, warping conspiratorial gloom into noirish modernism. This is a history with precious little stable ground, and whatever it lacks in moral clarity, it recovers in aestheticizing the experience of having your sense of historical meaning – of history as a divine arc – swept out from under you. Heroes who seem like dark angels partitioning the frame later feel like shadowy wraiths ready to do away with us.

Readers, this anti-radical picture preaches a sermon of democratic temperance that, in its context and ours, always risks contracting into acquiescence, a politics of tolerance that also threatens to suspend democratic initiatives – the need to change the world even if there are costs – wholesale. This film shivers at the thought of revolutionary fervor, which it presents as a slippery slope to the termination of morality that is also a desecration of the past. Revolution, in this film, is an immanent paradox, a vital upsurge of electrifying potential that is, finally, a premature conclusion to the song of possibility it presents. This is a politics of skeptical centrism, not meaningful critique.

This is also a politics that I am essentially skeptical of, and that I think has done far more damage to our vision of a better world than good, but, readers, this film is simply exquisite, not because the filmmaking excuses the politics but because it revises and reframes it. While he was most famous as a chronicler of the Wild West, filmmaker Anthony Mann’s surgical dissection of our belief in a bucolic past was not confined to American history. Reign, much like 2024’s Conclave, is essentially a parable about the shadowy contours of political change. Much like Conclave, it also wants to inform us that dreams of sudden change and visions of moral rectitude are really delusions of certainty, that real ethical vision is rooted in having the certainty to recognize how uncertain you really are. Unlike Conclave, Reign of Terror is pungently alive in its low-brow energy rather than consummately embalmed in its middlebrow professionalism. In Mann’s hands, revolution becomes a living embodiment of what one character calls a “perpetual state of violence.” It also becomes a very real exploration of the limits of neutrality, of trying to escape that violent revolution may sometimes be a moral good.

And that fear of change, with all its risks and disturbance included, may actually amount to political death. The film best realizes how celebration of procedure and decorum can actually be a conniving form of self-aggrandizement in the ease with which two seemingly opposite forces in the film come together. One particularly odious sort named Fouché (Arnold Moss) demonstrates a calculated submission to Robespierre’s power that is also an invocation of the dangers of the film’s own politics. “Which side are you on,” our lantern-looking hero Charles D’Aubigny (Robert Cummings) asks, to which Fouché’s sniveling response is “it looks like I’m in the middle.” The irony of the character is that, for audiences during the Cold War, this film undoubtedly resonated as defense of anti-radical centrism. In this film, it seems that there really isn’t any middle anymore, that there is no easy way to distinguish between our square-jawed hero’s apparently valiant liberalism and this smooth operator’s conniving and cutthroat political vacancy. Both of them are in the proverbial middle, and while Reign of Terror wants to designate one as the arbiter of the film’s moral compass and the other as the grotesque cynic with no moral compass, the film can’t but expose how difficult it is to tell the two apart. “You don’t know me and I don’t know you,” the hero remarks, to which the confidence man notes “that’s a good start.”

What, then, is Reign of Terror? Certainly, one way of thinking about it is as a form of milquetoast presentism, one that defends the centrist politics of its time via a story from another. But another is a vision of history not as a romantic idyll of harmonious progress but a dark reverberation of tenebrous morality, in which even the awful and the good can work together, or be indistinguishable from one another, in which righteous morality may be shallow opportunism, not only for the designated villain Robespierre but the hero sent to slay him. This is a film of cinematic obstructions, its gloriously rich blacks modeled as abyssal voids out of which literally anyone seems ready to reach in and take control, or to mutate from a righteous cipher for goodness into a distorted projection of its imaginers’ own disenchantment with possibility.Reign of Terror unfastens the very centrism it seeks to uphold as a virtue, exposing the difficulties of its own essentially moderating quest to wean people off of radicalism. In the cracked mirror of history, it holds the hypocrisies and confusions of the era that produced it up to its audience and emerges not only frightened of its apparent enemy but terrified of itself.

Score: 8/10