While the received wisdom about the Western genre presents it as an assured space of spiritual solitude or a canvas for self-betterment through restorative strenuousness, you’d be hard-pressed to find a Western more worried about its own beliefs than John Ford’s The Searchers. The only thing really working against the film is how thoroughly its reputation precedes it. Its self-critical nervousness has paradoxically been suppressed and composed over decades into a vision of the solemn, self-assured object imperially judging its forebears. This is a supposed masterfulness that the film itself may not need, nor ask for. But, of course, that is the difficulty, and the paradox, of John Ford. The Searchers is entirely aware of the cultural baggage it carries. Far more than era-concurrent works like Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73, it self-consciously courts, and creates, the mythopoetics of the frontier space as a moral battleground – rather than Mann’s amoral void – on which the fate of the proverbial nation is to be staked. Its screenplay by Frank S. Nugent, based on the novel of the same name by Alan Le May, is transparently freighted with the heavenly wisdom of the noble stranger archetype, the paradigmatic American: isolated in their heroic, if tragic, dignity while being able to fluidly move into and out of various social milieus without being “of them.” This is a film that seems to have recognized how important it was before it was released, something that usually spells death for a living, breathing work of art. Yet rather than solidifying itself into a work of serene self-criticism, the interesting thing about Ford’s film is how worried it seems to be that it hasn’t actually figured out what to say about the genre laid out before it. The genre, in Ford’s vision, is not a passive resource to be either churned into self-conscious mastery nor to be dismissed or depleted into a ruse, which of course would only be another way for the film to celebrate its own assurance that the genre was morally repugnant. The West, in The Searchers, is neither a landscape to excoriate nor to celebrate. It is a vast store of uncertainty, a wellspring of consternation.

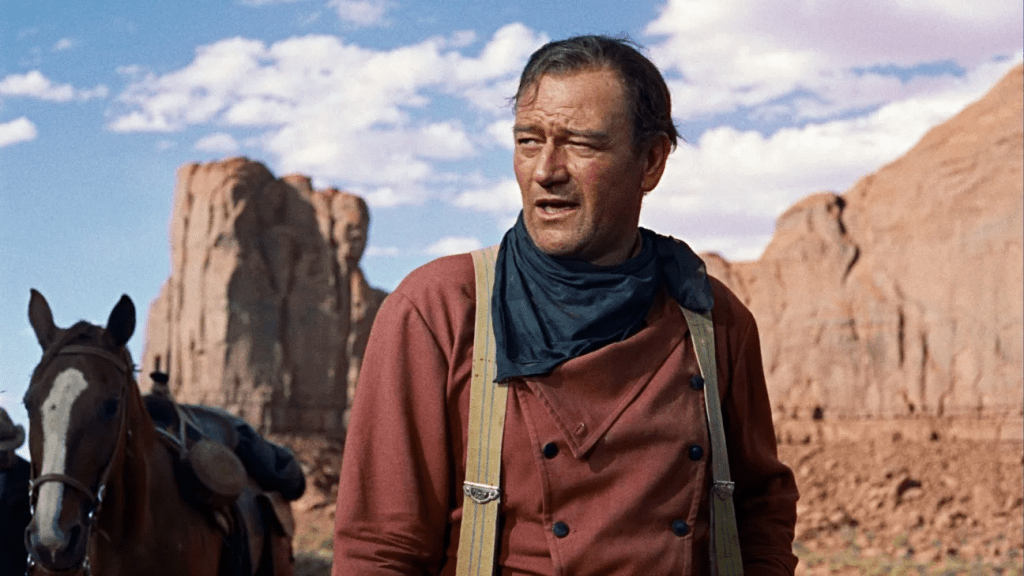

That doesn’t mean The Searchers doesn’t court the favor of its genre. The film’s interest, unlike so many heroes of the classic West, is that it transparently can’t escape its history, which means it must draw on the very mythos it can’t figure out. Wayne’s Edwards, the Western wanderer, is clearly the most capable man in the film, but he is also the most dangerous. He remains the film’s icon figure, like any good Western, but he is also the vortex around which the film distorts itself and the precipice it must confront but cannot fully peer into. While Wayne’s famous character introduction in 1939’s Stagecoach projects an imposing, all-consuming monolith overcoming a figurative landscape which he himself apexes and dwarfs, here he enters the film strolling in from a landscape that still seems to consume him, into a door that cannot fully protect him. While Stagecoach literally enacts the triumph of human over landscape in that moment of charged, almost phallic agency, The Searchers is a world in which humans seem essentially trapped in a tide of violence and vengeance that defrays the teleological, progressive structure that Manifest Destiny was predicated on. This is a not a man erected as a savior and defiler of a material, almost anthropomorphized abundance, but a lonely fellow who has come in from the cold, only to find that he imperils the very domesticity that he claims to protect.

In the film, Ethan will take it upon himself to conduct a search for Debbie Edwards (Natalie Wood), his young niece who is kidnapped by a Comanche war party led by Chief Scar (Henry Brandon), traveling with the begrudging company of Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), a 1/8th Native American man adopted as a child by Debbie’s family. As everyone now knows, the film will eventually turn not on the question of whether Ethan can save Debbie from the external threat of Scar, but whether he will choose to save her from himself, to extinguish his barely hidden rage against Native Americans enough to not kill her upon sight for having been raised, after her kidnapping, as a Native herself. Thorny enough, but The Searchers troubles itself well before formally introducing that prospect. Even from the beginning, the film’s structure is at once constrained and diffuse. The “search” takes upwards of five years, and it plays out in a poetic haze, a frontier fugue of gestalts and ellipses. Rather than funneling us toward a logical climax, it feigns one several times before protracting and straining if not actually defiling them. When things coalesce, it finally raises an implication we – it – had only dimly recognized beforehand, and it finally resolves this question in a sudden about-face, a kind of fearful shudder of the repressed lurking within it. When Ethan does – famously, suddenly – choose to save Debbie, we wonder if the film actually believes itself. Just what, and who, and why, we are supposed to root for anything is very much an open question. Ethan becomes a kind of cosmic anchor, in one sense, a tour guide through an embattled, purgatorial landscape, but his final decision is decidedly not presented as a redemptive gesture. After it has been searching for two hours for reasons to believe in itself, all the film can do is will a gesture of humanity into existence, one it seems to know we will struggle to believe.

Not that Ford’s aim was to expose the fertility of the American imagination and experience as an icily sterile mental void. Ford was not some kind of post-modern deconstructionist, but while he could be a conservative in a small-c sense, he never seemed like an ideologue. His characters, at least in this film, walk through the spacious, gaping expanse of the Wild West as though it were, for once, genuinely unknown narrative territory rather than merely a prefabricated canvas for a consummative story of masculine achievement or a lullaby for a pre-modern savage pastoralism in need of civilizational taming. The strange thing about Ford is that he is able to do this within the seemingly celestial contours of an enchanted text, unlike, say, Budd Boetticher, whose films were restricted by necessity and develop their punch out of their ramshackle naturalism, or Samuel Fuller, whose films are bullet-ready newspaper headlines. For all his critique, Ford was still very much a willful poet-conjurer of America’s national identity. The Searchers never abandons this mode, but rather than treating poetry as a refuge, it finds a national ideology reverberating with unresolved tension and buzzing with a natural chaos and complexity ready to be harnessed. He takes on, rather than rejects, America’s vision of itself, and then he follows it until it begins to crack.

Ford treats the West as a battleground for the soul, yes, but for all his shaman-esque abilities to divine poetic truth from the harsh landscape, The Searchers is also a surprisingly literal, tangible, physical space, a world of cyclical confrontation and moral compromise. For all his super-sensory, superstructural insight into the milieu of the American imagination, Ford’s is also a surprisingly materialist take on the West, and his film is interested in feeling out that landscape more than predetermining it. You get the sense that he wants, and maybe is still trying to, believe otherwise, but he can’t but reveal a morally compromised landscape of factional strife and uncomfortable affinities in which violence done on others turns you into your worst enemy. At one point, Ethan ravenously shoots a buffalo not to eat it but simply to ensure no Native American could have it. Ford presents this (with editor Jack Murray) as a montage intercut with the U.S. army, the very force Ethan, an ex-Confederate, seems to resent, presented initially as either an interruptive threat or a savior here to vanquish Ethan’s pre-modern, pre-liberal hatred. Yet we soon learn that they have just come from violently murdering a seemingly peaceful Native American village themselves. Here, the enemy of Ethan becomes his equally murderous double, a chain that extends when he finally meets Scar and both half-mockingly comment on each other’s command of the other’s language. The film depicts both men as essentially cruel wounds bruised into resignation by a potentially irreparable landscape. Scar even wears Ethan’s old Confederate insignia, a doubling that positions Ethan as a man trapped in a past world and as a kind of other and which frames Scar as a renegade outsider from a somewhat “backward” way of life himself. These are politics of a different time, and they don’t exactly move beyond a kind of moral equivalence wherein both men may be equally bad, but The Searchers is aware of the complications it raises and that it is not fully aware of how to parse them. While Ethan signifies classical American masculinity, there isn’t really – within the text – any sense that Scar is “worse” than him. He’s a harsh, brutal man, but he is Ethan’s double more than his antithesis.

In a sense, though, it is only Ethan that holds on to his illusion of control, maintaining a restrictive racialism in which Debbie must be killed for abandoning her whiteness and Martin cannot be considered family because of his “drop” of Native American ancestry. It is Ethan who essentializes races though. The Searchers itself depicts Native Americans not as a unity, and the other Native American tribes we meet in the film don’t seem to have much use for Scar either. And if it is true that Martin was rescued by Ethan as a child after his parents were killed by Scar, we also learn that Scar engaged the raid because his own sons were killed by Anglo settlers as well. The other interesting thing about Ethan is that, although he is the only one who genuinely rejects any kind of integration, he is also the ablest interpreter among the white characters of Native American cultures. He shoots one’s eyes out after he is dead because, to the Comanche, one cannot move into the afterlife without their eyes. The film presents this as a murderous, hateful act, but it is also a strange sign of awareness, if not respect: only Ethan takes their culture seriously in any respect at all, even if because he refuses to allow it to enter his. Ethan’s unallowable malice immunizes him from the film’s vision of a “good” America, but the text also proposes that genuine multiplicity, a sense of connection with and via difference rather than homogeneous assimilation, is not exactly found in the white family’s “benevolent” admittance of Martin provided he act 100% like them.

At times, The Searchers feels like a cinematic lullaby for a vision of uncomplicated reality propagated by some – many, but not all – classical Westerns. It might more accurately be seen as a cinematic nightfall, a film that is still in love with the light it wants to keep up but knows it can’t and probably shouldn’t, and a film that investigates the murmurs of irrepressible otherness that emerge when the moral idioms that guide its soul are dimmed. Ethan is not a guardian of imaginative prosperity or pastoral tranquility. If he is canny and absorbent enough to learn from other cultures, he isn’t an image of noble solitude collapsing distinctions into himself so much as a fragile monolith of a violent engine’s dream about itself. And The Searchers is not a rehearsal of a national mythology but a terra incognita, not so much presenting as crossing paths with a horrid quagmire of a nation grappling with feelings of existential purposelessness, trying to acknowledge a foundational violence it seems wholly unprepared to truly grapple with. The title is accurate in more ways than one. It is that inability, that it searches for an answer it never arrives at, that makes the film meaningful for us today, that marks it as a deeply material reckoning which tinges any restorative hope with an undercurrent of severe violence always ready to be unleashed.

Score: 10/10