The ‘60s music movie, in its many permutations, was an attempt to diagnose the manifold mutations of a shifting sociocultural landscape. D.A. Pennebaker’s seminal Don’t Look Back figures Bob Dylan as an almost malevolent blank void courting and interrupting power, a clown prince puppeteering every inch of his relationship to the audience’s desire and his prismatic manipulation of it with Warholian ineffability and Keatonesque implacability. Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night frames The Beatles as impish vagabonds harnessing the recalcitrant energies of an unreconstructed, uncontained modernity. Bob Rafelson’s Head, not to be outdone, mounts a vision of The Monkees as tortured poets of a world gone awry and unable to put itself together again. In these films, without always stating it, pop culture becomes a battleground for the fate of the future and an exploration of the limits of authenticity. In rock and folk music, the cinema of this era discovered a way of interrogating film’s very capacity to index reality itself. What, finally, did it mean to “document” truth when truth itself was a maelstrom, in which the method of inquiry itself – the visual representation of reality – confronted a subject that made visuality itself an unstable ground.

Gimme Shelter, a searingly banal documentary by direct cinema auteurs Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, seems, at first glance, to exhibit no such complication. Nor does the film’s subject, The Rolling Stones. Unlike Dylan, they do not thrum with calculated incalculability. They exhibit none of The Beatles’ self-aware, rakish charisma or peripatetic malice. When they are off-stage, they seem neither prey to nor predators of the forces that the Monkees found themselves wound up in. For the most part, they seem entirely unaware of the world around them, abstract ciphers approached by unknowing cameras.

The aforementioned movies and the aforementioned musicians all project a sense of interdependence and estrangement from the cultures that produce them. They are complex arrays of personal and social complexes, reflecting the ambiguities of gazes and desires that are offered, given, rescinded, and contested. Gimme Shelter, conversely, more or less depicts The Rolling Stones, who seem so happy to characterize themselves as willful collaborators with dark forces in songs like “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Paint it Black,” as entirely helpless. Gimme Shelter punctures the air out of countercultural acts of self-mythologization and optimistic social liberation not, as is usually written, by freighting these aspirations with self-inflated import and forcing them to confront a demonic ground labelled “the end of the 1960s.” What the film offers is more frightening and more thoroughly deflationary. Gimme Shelter implies that it may have meant nothing at all in the first place, that its most shining surfaces may have had much less going on underneath.

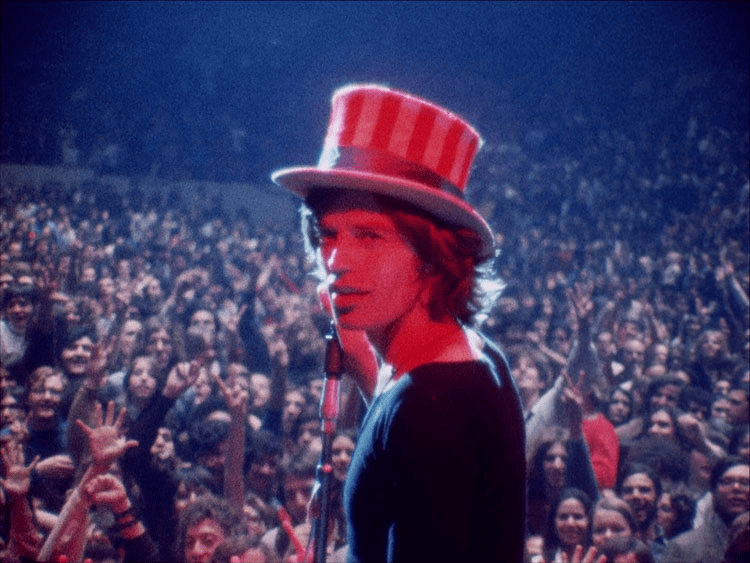

This film does, of course, maintain more than a passing interest in the mythology of the decade. Indeed, more than any of the aforementioned films, it makes it nearly manifest in the structure of the film, which alternates between transportive performances by the Stones and deconstructive images of the band watching themselves perform, experiencing their own presence and mostly seeming disinterested and displaced. Of course, they try to depict themselves as poets channeling and directing wider energies. Front man Mick Jagger wears an American flag magic hat and a cape on stage, positioning himself as an alchemist of American cultural manna transformed into personal gold. And I say this as someone who is very much an acolyte of the band, to be clear. Whatever their faults, they do seem to tap into harmonies and resonances far beyond their bodies, suggesting that they may be empty inside only because they are so in tune with an outside that we cannot even imagine. “Love in Vain” becomes a reverie, an act of celestial serenity. “Honky Tonk Women” becomes a pagan rave-up, Jagger a strutting scarecrow attracting, frightening, and fending off ravens. It’s galvanizing stuff. Yet the dark implications of this position are exposed soon after. Commenting on Tina Turner’s deliciously self-possessed performance of “I’ve Been Lovin You Too Long,” Jagger can only muster a thoroughly degrading “it’s nice to have a chick.”

Of course, the reason we talk about Gimme Shelter today is the ending, played not as a sudden plot twist but an expectant gaping maw to which the film’s, and the culture’s, own energy was inextricably winding up to. When the band begins “Sympathy for the Devil,” Jagger aggrandizingly intones that “something funny always happens when we start that number.” Soon after he does, a Hell’s Angels member looks back at him, angry and seemingly more in tune with the violence of an era than Jagger has any idea of at all. The rowdy motorcycle gang, of course, was hired by the band’s management to cut costs, and the chaos of the famous Altamont concert which served as the climax of the tour this film chronicles, infamously resulted in the stabbing and killing of a crowd member by one of the Hell’s Angels.

When another Hell’s Angel member speaks in Jagger’s ear about a death that the film seems to know couldn’t but happen, even though we haven’t been told about it yet, something seems to violate the performer’s shell.Jagger’s convulsions suddenly mutate from a self-mythologizing pseudo-spontaneity into a (seemingly) more genuinely violated body coming undone, a return of the repressed as probing and disturbing as any in cinema. For the one and only time, he seems completely affected by a violence that he cannot hope to name.

Or maybe this, too, is part of his performance. Perhaps it is the film’s disturbing poetry, a kind of reverse Kuleshov effect wherein our knowledge of the violence, and our cultural memory of the 1970s, frame what is actually just the same motion in two different ways once we assume he knows of the killing. Perhaps Jagger is still up on stage enjoying himself. Perhaps he was just being informed to finish the set early, an otherwise none-the-wiser avatar engaging in action that he wants us to read as gyrating, gesticulating pleasure. Soon enough, we see a two-shot of a hippie blissfully dancing and another shaking in apparent fear in the same image, a cinematic photo-negative that asks how these two things could be occurring at the same time, or what it means that they might actually be the same reaction, connected by some amoral force called “the 1960s,” with all of its attendant associations of libidinous spontaneity and playful emancipation.

Nothing, it seems, could fully capture this tension or answer this question, and when Jagger finally tries to address the killing on stage, he can only muster an automatic sounding “who’s fighting and what for?” His wholeheartedly pathetic “you can do it/it’s in your power/let’s just keep ourselves together” is cunningly ironized by his two-tone shirt split right down the middle, an outfit that seems to figuratively bifurcate him in the frame. Although this is a “documentary,” Jagger’s real performance doesn’t seem very different from Henry Gibson’s hopeless “This isn’t Dallas” at the end of Nashville.

In that 1975 Altman film, it is death that ushers in stardom, an emergency that provides an opening for the emergence of a new star to mount her moment in the sunlight in Altman’s scathing indictment of the entanglement of spectacle and spectrality, pleasure and violence. Although it is difficult to imagine the Maysles and Zwerin not finding some kinship with Jagger’s hopeful claim that Altamont could be a “microcosmic society,” their film seems even more pitiless in its curiosity than Altman’s warm probe into the American music industry. The film’s perspective seems encapsulated in a late film shot when Jagger himself briefly sidles in from the side into a lengthy shot that has been almost entirely focused on the violence around him, as though he is jealously re-announcing himself as the focus of the frame. He is the star performer here, but the film suggests that he might really be obfuscating a deeper truth that we have been trained to either expect or accept.

Re-watching the footage in slow motion, we see the knife enter the back of Meredith Hunter at the moment of it piercing his body, an image captured with the chilling finality of a De Palma film. The sense, though, is not that of an underground violence shockingly made apparent but of, simultaneously, an obvious fact bluntly acknowledged and an opaque mystery still hopelessly unanswered. As we watch the procession of attendees leaving, passing like ghosts in the night of a vision born and extinguished, or maybe a spectral enactment of a hope we’ve been told died long beforehand, Gimme Shelter ponders what, if anything, could have saved a hope that the film ultimately seems doubtful of. The real revelation is not so much the footage of the murder as the film’s final shot: a freeze-frame on Jagger himself, looking maybe displaced or maybe hesitant or maybe weary, but, finally, all too ready to act like nothing has happened, all too needing to let the show go on.

Score: 10/10