Aficionados of Lucio Fulci, perhaps the most savagely lurid of the most savagely lurid of the Italian horror giallo maestros and the least willing to sanctify his violence in a beatifying aura poetic abstraction, might be surprised to know that he did not fully commit to being a horror specialist until his sixth decade on this earth. His genre classics, which dare to descend into the darkness of the human soul at its most unvarnished, are cruel conduits for seemingly arcane, voracious forces that seem to congeal out of an unclaimed past. Yet even when he eschewed the formal trappings of the horror genre, Fulci seemed to tap into devious currents nonetheless. His was a cinema charting the existential breakdown of enlightenment ideals, an intrepid explorer of the darkness of the light. His greatest films merely use horror as a canvas on which to the frayed boundaries of reason and the murkiness of faith in progress avail themselves before us. His films, sloppy and with awkward edits that seem to come from some frayed corner of the mind, are dark impastos that stare at what we’d rather look at with downcast eyes, portraits of human abjection as vicious and primordial as cinema has ever produced.

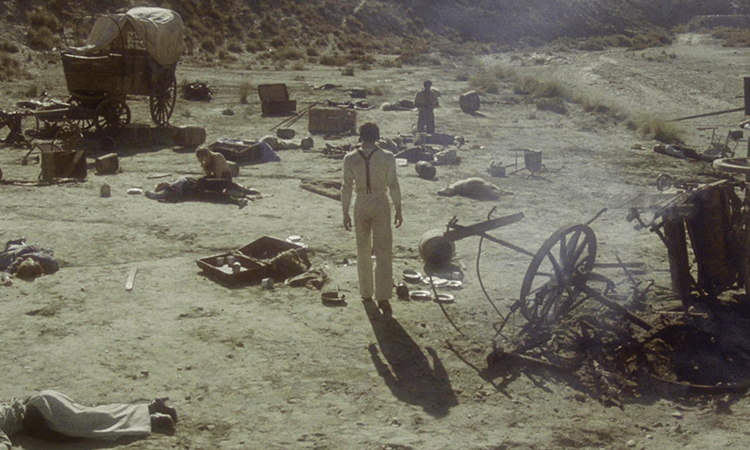

Case in point: his downright malevolent travesty of an Italian Western, Four of the Apocalypse. While Italian filmmakers like Sergio Leone had exalted the genre as a hallucinatory canvas for piety and blasphemy to battle it out, and plenty of other Westerns essentially understood the genre as a boundlessly open space of anarchic creativity, Fulci’s Western is a shadowy vision of disgruntled sociality captured with Fulci’s primeval immediacy and narrative inexplicability. It begins with four characters in search of an exit, condemned souls who are, in a ruthlessly wicked gesture, only saved from a vicious massacre by their imprisonment. It ends with one interloper who found and lost a family set adrift in the desert sea to probably repeat this story time and time again. In the intervening span, Fulci turns the inviting landscape of the West into an unforgiving, unfathomable vortex that is also a cosmic abyss, a landscape that seems to extend for eons and to coagulate into a portrait of celestial nothingness.

That it is “adapted” from multiple essentially forgotten dime stories from the era gives it the aura of a dimly remembered, scratchily told campfire tale, one that drifts between hazy segments hastily stitched together with a pair of rusty shears. The stories themselves are meaningful only as portions of a corpus, vertebrae of a national imaginary’s body that could survive without any of them in particular. They lack specificity and are endlessly excerptable and exportable, able to become one another without much being lost in translation. Four of the Apocalypse seems not to “adapt” a single text but to call forth the West’s patchwork vision of itself.

More than simply tapping into the Wild West’s primordial id, Four of the Apocalypse also seems to promise and then sabotage the genre’s invitation to remake the self, to find a new home, to seek possibility through adversity. It offers us a ragged crew of potential wanderers who could become a forlorn family bonded in blood, but their vagabond interdependence ultimately suggests a peripatetic estrangement rather than a wholesome togetherness born of necessity and blossoming into creativity. These characters occupy the same physical space, certainly, but seldom the same headspace. They are Stubby Preston (Fabio Testi), a rakish professional confidence man, the honest and caring prostitute Bunny O’Neill (Lynne Frederick), Buddy (Harry Baird), a troubled, humanistic African American man whose mind floats in an out of relation to the others, and Clem (Michael J. Pollard), an alcoholic who speaks in sideways slurs. While they make up a transient tribe for the duration of the film, theirs is a gossamer friendship, one they wear easily only because it appears not to go too deep.

Stubby, our gambler and ostensible hero, uncannily recalls Keith Carradine’s genial faux-cowboy from McCabe & Ms. Miller from the previous year in both physical appearance and looseness of being. Yet Fulci’s film suggests that we are in the presence not of an innocent dressing up in the costume of a romantic wanderer, a la Carradine’s Kid or the dreamy-eyed confidence man McCabe, who believes himself to be both above and within the capitalist rhythms of a risk-taking bootstrap identity, but a cunning charlatan who somehow honors the actual artificial spirit of the West’s mythology.While Altman’s film shades the lone wanderer as a forlorn poet teetering around the frayed edges of an ambivalent and ragged myth, Four of the Apocalypse evacuates the myth of gravity and then stretches it as thin as it can possibly go by spreading the characters out within a desolate landscape to the point where little coherent narrative around them can coalesce. In its piecemeal story of four strangers making a family for themselves on the frontier, Fulci travesties America’s national mythology of found families and democratic communities bound by experience and circumstance rather than lineage or history. Treating this as a narcotic for America, he instead turns it into an ineffable chronicle, a dispatch of the damned. Fulci mutates the aspirational story into a ghostly procession of lost souls who only intermittently come to life, but who always suggest just enough awareness to let us know that they know that they’re dead.

An awareness the film itself so obviously exhibits. One tombstone eulogizes a character “born in 1892,” a date that is explicitly impossible given earlier information in the film, indicating that this, too, is set in an indeterminate mythic time-space that shows how the Wild West was always on its way to a demise. This is a reality unclarified in the text but which suffuses the disfigured narrative rhythms and the pallid cinematography. “Why’d he do it?” one character asks about a crime, while speaking to a doll. The only answer the film can provide is a clear cop out, but also one that speaks to the time period’s vision of itself, a final forgettable answer in a forsaken land, yet a place pulsing with the sheer life of a cinema unterrified of acknowledging its genre’s debt to death and its own failure to coalesce around any convincing or compelling answers to its questions.

It is only in this cinematic life that Fulci finds fringes of transcendent mutuality in the penumbra of his vision. Genuine frissons of play and ephemeral release effuse at various passages of momentary freedom the characters find while waiting around together in, say, an empty barn they are tentatively cohabitating. When the wanderers cross paths with a collection of Swedish immigrants in search of more hopeful land, Fulci offers a momentary filigree of connection rooted in mutual exile. “Very far away, like Africa brother,” a Swedish patriarch remarks to Buddy as they go “searching for our brothers in this land of freedom,” tipping his hat to American wanderers united in a shared refusal of subjection. Yet the Swedish immigrants find only death, and the African man Buddy seems to dissipate as his mind’s edges seep out into the ethereal gloom of a ghost town. In such moments, Fulci turns his film into a reminder that the impromptu American family centering the film was not easily offered to people who were not white, a haunting echo of centuries of a people finding no easy home in the land of the living.

Although Fulci treats the era as teeming with moments of genuine beauty, momentary communion, and nurturing togetherness, it is also, more obviously, ravaged by uncertainty and perpetually teetering on potential violence. All the more so once Chaco (Tomas Milian) enters the fray as an all-too-obvious Manson facsimile. Of course, Manson himself played “cowboy and Indians” on his fake, abandoned Western ranch, a beleaguered corpse of a once thriving movie industry that, itself, so often trafficked in hollow taxidermies of past dreams. Manson understood himself to be a particularly skilled necromancer, a conjurer channeling the violence of the nation’s history back onto itself. And if the rebellious spirit of the 1960s channeled, or understood itself to be channeling, a history of deceased wanderer-poets and rebel-heroes throughout American history, Four of the Apocalypse finds a mytho-historical tapestry that may be unworthy of such redemption, a nation slouching toward Bethlehem and propping itself up on the corpses of a national violence it is too afraid to name.

Score: 8/10