Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a film about the melancholy of desolate spaces and the overpowering intimacy that can take up residence in them. A sensory romance to rival Wong Kar-wai’s aching, radiant exploration of unstated affection In the Mood for Love, or Alain Resnais’ oneiric portrait of fractured connection Hiroshima mon Amour, Portrait is the rare romance that explores the very nature of its genre. Portrait is really a meditation on the form of connection and love itself, on the way it breaks the self into many dispersed parts, the means by which it creeps up on you, how it takes over the soul and consumes the mind. Fundamentally, the film asks what it means to relate to another person. It is certainly, in this case, a “queer” film, but the relevant sense of that term is less that the two lovers are women than that the film troubles any stable or foundational understanding of what desire itself ought to look like. And I do mean look like. In addition to bewildering any conventional desire to label the film a specifically “lesbian film,” Portrait offers romance in a simultaneously expansive and fragile sense, as something that occurs in the gap between the mind and the eye. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is an uncommonly perceptive exploration of perception itself.

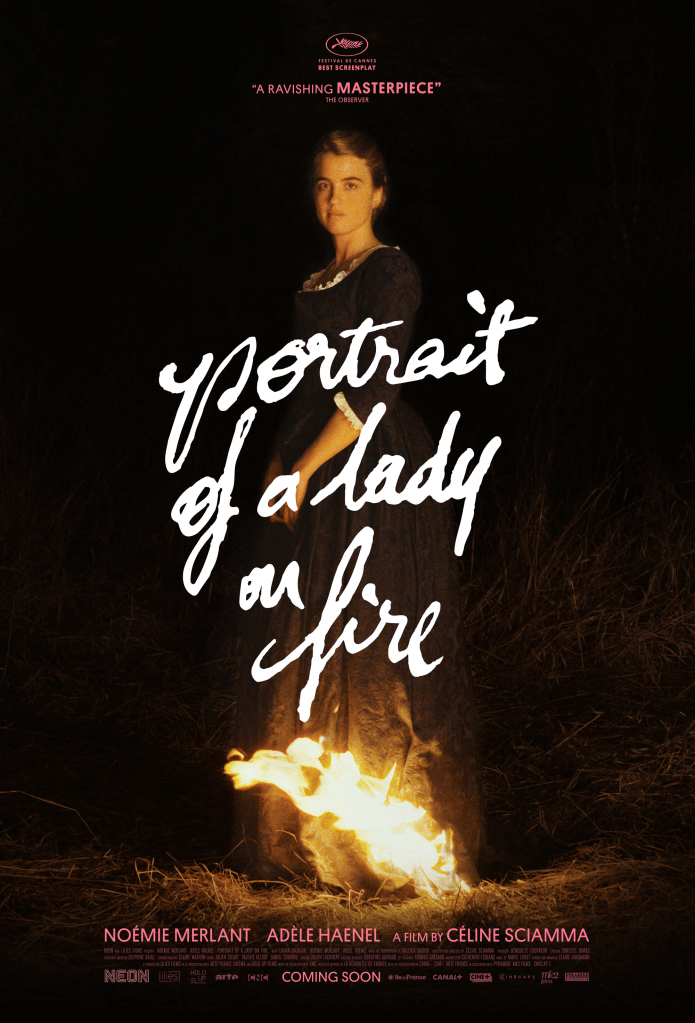

Nominally, the “looker” is Marianne (Noémie Merlant), commissioned by a Countess (Valeria Golino) to paint a portrait of her daughter Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), which we intuit is de rigeur prior to an aristocrat’s impending marriage, in this case to a nobleman of Milan, who Héloïse has never met. Héloïse cannot know that she is being painted, which would indicate her agreement to the marriage, which she steadfastly refuses. She is only home from her chosen life in a convent because her older sister has recently committed suicide. Under the pretense of being a companion, which becomes the actuality of being a friend and lover, Marianne accompanies Héloïse on daily cliffside walks while she discreetly memorizes the contours of her face for a portrait she completes behind closed doors. However, when Marianne completes her portrait, she refuses to maintain the façade and tells Héloïse, who rejects the painting not, as we expect, out of a refusal of her impending husband’s desire but out of a desire to court and cultivate the beauty located in the artist’s desiring eye. The painting, Héloïse finds, doesn’t capture her fire, so to speak, nor the fire of Marianne’s attraction to her. Knowing that the painting reflects a desire of Marianne’s that remains untapped, both for observing Héloïse and for the possibility of creating with her, Héloïse decides, willfully and for the first time, to pose for Marianne.

Unlike most romances, Portrait recognizes that love is an intersection of fluctuating desire with fluxional relations of power. It never disguises the imbalances that construct the relationships on screen, the tension between viewer and viewed that it understands as the necessary precondition for love, desire, and friendship to flourish in the first place. Marianne, as the painter, clearly exerts a kind of clandestine power over Héloïse initially. She recognizes elements of the relationship, playing out a version of the story, that Héloïse is seemingly oblivious to. When she more formally paints her, she gets to look directly, to study and divine an essential set of truths from the ambiguities of the observed surface. Yet Héloïse also gives herself to Marianne to do so, and she transfixes Marianne in a way that suggests that her own apparent vulnerability before Marianne hides reserves of solidity. In giving themselves to each other, in offering each other the gift of a power to exert a kind of control over the other, they become the centerpiece of Portrait’s invitation to ponder the potential for perception and reflection to overcome the limits of the hierarchical gaze. This includes the younger housemaid Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), who the two other women play cards with, accompany to a dance, and perform an abortion on. Every scene is thick with pregnant pauses of unstated emotion, and with the potential of living and growing within the ambiguities of unequal relations.

Portrait is also, necessarily, a celebration of how art, and the process of creating art, and of observing art, can be a nearly divine channel for gestating these potentials, for cultivating a reciprocal attitude toward others. Art, the film understands, allows us to engage the world by perceiving and creating with its flows, resonating with it by creating something removed from it. Portrait is a spellbinding essay on creativity as an expansive and life-binding enterprise, on giving up part of oneself to a strange other – either person or production – and taking the matter of the world into your eye and hand and heart to reflect it back onto a canvas that you hope will gift you more of yourself in turn. “May I be curious?,” Marianne asks Sophie early on, and Portrait treats curiosity as a canvas of the becoming self.

Observation, then, is a shared relation in Portrait, not a purely horizontal one but never merely vertical or simply hierarchical either. A recurrent shot of Marianne from directly behind her head, and another from her point of view looking at the back of Héloïse’s head, present a dialogue between a need to look which the film in no way frames as merely a penetrative and oppressive “gaze,” and, on the other hand, the necessary opacities that remain inextricable to that act of observing. And just what and who we are looking at is slippery as well. At one point, Marianne turns to see Héloïse as a ghost in a doorway, a painting of the mind as ambivalent and observant as the real artwork. Even more telling is an early shot of a woman walking in a green dress. We initially assume we are watching Héloïse’s introduction wearing her painting ensemble (the wonderful costumes are by Dorothée Guiraud), before a pan up reveals a slightly different perspective that enforces the multiple layers of labor behind the beauty of the curated image, not all of the work being the painter’s.

Fittingly, then, Sciamma and her filmmaking partners turn Portrait into a quiet conspiracy of light and space, texture and tempo. Portrait is a languorous film, but its languorousness has a libidinal quality, moving us to an imaginative position of sheer receptivity. Claire Mathon’s cinematography initially presents as naturalistic, but there’s something in its multi-shaded complexity that draws out currents of reality beneath the apparently sensible. She turns the manse in which most of the film takes place (beautifully production designed by Thomas Grézaud) into a dance of soft light, a dark space from which the illumination of desire still seems to constantly emanate. The film’s look echoes paintings from the late 18th century, moving on the path to a romanticist vision of a vital, active world. Sciamma’s camera, with its long, often-unbroken takes as characters explore the house, frames characters as they confront this vast unknown in even the most mundane of spaces.

And sometimes we can only sit within this unknown. In its short, devastating epilogue, Marianne recounts two stories. In the first, a woman observes a portrait of another woman with a secret, more authentic portrait clandestinely hidden within the larger one. The larger image has an audience of thousands. The smaller one is only suggested, and its audience can only be the only person who knows how to look for it. This is a glimmer of quiet rebellion, a fringe of old love still burning folded into another image that may seem less authentic at first, but which might learn from the more silent, hidden image over time, and which may reveal even more secrets than we can currently know.

In the second part of the epilogue, one woman watches another woman listening to music as her face quivers through dozens of emotions swelling up, a public response to art shared by hundreds in the same theater and a more private reaction to dormant emotions released by the encounter with the music. Her face here has an audience of two: the woman whose face it is and the woman watching unbeknownst to her, whose face in turn is animated through a current of expressions, drawn back into a shared experience from across the room. These are portraits of women on fire conjuring memories, sharing a secret, they cannot express in words, but which intimate themselves in the ambivalence of perception itself.

Score: 10/10