On the back of an ostensibly simple fable about two lions attacking a railroad camp in Kenya at the turn of the 20th century, The Ghost and the Darkness scaffolds so many half-baked ideas about the relationship between Hollywood filmmaking and Western colonialism that it is hard to tell whether it is more or less complex than it initially seems. Triangulating Western escapist fantasia, heart-of-darkness cynicism, and a malarial mood of colonial ennui, the film tries to cover all its bases, to be at once heartfelt and disaffected, hard-hitting and sentimental, critical and rip-snorting. It is, finally, the film’s failure to truly understand itself that makes it somewhat compelling, so far as it goes.

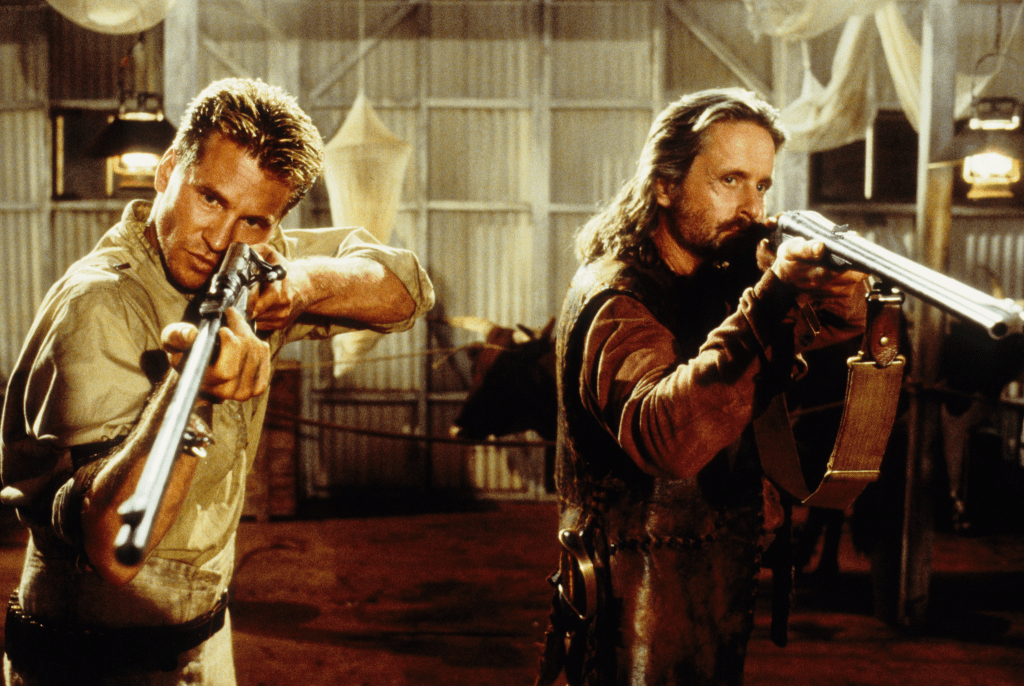

Writer William Goldman and director Stephen Hopkins heavily freight the film’s essentially B-movie plot (killer lions on the loose in Africa, two white men go on the hunt) with what alternately feel like poetic evocations and pretentious intimations of a screenplay trying too hard to impress us with its underdeveloped understanding of itself. Loosely, it tracks Val Kilmer’s John Henry Patterson, a military official tasked with getting the completion of a bridge in Kenya into shape, only to learn when he gets there that two abnormally aggressive, possibly supernatural, lions, popularly nicknamed The Ghost and The Darkness, are killing the workers in scores. After several thoroughly unsuccessful attempts to kill the lions, Patterson is joined by Michael Douglas’s American big game hunter Charles Remington, who has much to say about killing threatening animals and more to intimate to Patterson’s soul about the nature of man and modernity.

Or so the film thinks. Douglas’s mid-film presence substantially increases the film’s watchability, but it only exacerbates its lingering conceptual confusions. Remington suggests churlish American indiscretion, unsentimental humanism, disaffected irony, and cunning individualism in equal measure. He is the kind of figure who has no use for colonialism in theory, but who is entirely willing to use it when it suits his investment in killing animals. The film begs the question: what do we do with the fact that Douglass’s American warrior is self-evidently the most palpable presence in the film, and one the cameras are both ashamed of and fascinated by? Is this meant to signify the superiority of American forms of imperialism, favoring careless, violent insouciance, over British steadfastness and discipline, both of which, of course, are more myth than reality? Or does it suggest the dangers of American charisma as a promise of energy that only constrains further? Douglass, commenting on one of Patterson’s failed traps, notes that he once tried the same thing. It failed, but he remarks, it was still a “good idea,” suggesting quite a bit about the film’s vision of American style know-how and adaptiveness, including the potential necessity of killing oneself, and many others who don’t have a say in the matter, along the way. But one leaves the film less than entirely sure what it actually thinks about Remington, other than that Douglass is enjoyable with a vaguely Southern accent.

It certainly does want to think about them, though. When one African man, nominally referring to the lions, responds that the “devil” has come to Africa, Remington smirkingly agrees: “I am the devil,” before he commands a tribe of African men to run toward him as efficiently as the lions get them to run away. In another scene, another African man looks skeptically at Kilmer and then turns to mystically swaying waves of tall grass portending evil to come. One final turn back to Kilmer both settles the metaphor – Kilmer is this uncertain, protean force, a harbinger of destruction as much a celebration of cosmic, masculine energy, of what Theodore Roosevelt called “barbarian virtues” – and unsettles it insofar as it leaves us wondering why we are meant to want these two men to kill the lions even as they seem unable to grasp their own relation to them. During a campfire scene, one of the film’s designated “reflective interludes,” Remington waxes poetically on the nature of change before wistfully wishing that the past is “all gone, but I hope it stays here,” in Africa. This great white American hunter clearly connects with some of these African men – which the film implicitly understands as a shared sort of rugged refusal of modernization – but is this something the film believes or deconstructs? Does it care which?

The lions, which are transparent corporealizations of centuries of colonialist violence and extraction, increasingly seem like the two white lions who star in the film, Kilmer and Douglas, actors who work in different but inevitably linked idioms of masculinity essaying characters who embody different yet clearly stitched weapons of Western colonialism. There’s no two-ways about this. Many of the steely, intent-minded close-ups on lion eyes are paired with similar reflective close-ups on the two stars. They even color-code the two lions in the same hues (lighter cream-tan and darker burnt umber) as Kilmer’s and Douglas’s outfits. The film posits that in killing the lions they are destroying those aspects of themselves that are oppressive. But it also implies, in Kilmer’s case especially, that this might simply be a means of denying their own complicity in these very systems. The lions, as it were, are both embodiments of an all-devouring colonialism and of those renegades who seem to fight it but cannot actually disown it.

Take the aforementioned scene with the trap. Kilmer’s character strands three brown men in one side of an iron box to draw out the lion, to be trapped in the other side of the box. This set-piece certainly suggests the film’s critical cast: when the men shoot at the lions, most of their bullets hit the bars and ricochet back near themselves, none-too-subtly suggesting that Kilmer is as much a creature toying with and using them as the nominal beast is. William Goldman’s stated interest in his screenplay was to fashion a film equal parts Lawrence of Arabia and Jaws. Certainly, Remington does exhibit a distinctly Quint-like madness, and the film strains toward Spielberg’s ability to contrast different types of masculinity in crisis. Yet Ghost only occasionally glints at Lawrence’s understanding that its white savior hero was really just another cog in an imperial machine. Occasional thoughtfulness aside, the biggest takeaway of the trap scene is simply that we sure hope they kill these lions. That’s not nothing, but Goldman’s screenplay clearly wants us to know that it has more on its mind.

This is, if I hadn’t made it clear, a sloppy production, but also oddly straight-faced and buttoned-up. It is, at any rate, better at the level of the scene than the structure. The lion attacks, for one, exclusively veer from good to great at a purely corporeal level, and the film is consistently adventurous in its expressionistic framing of them. But The Ghost and the Darkness is perhaps best illuminated through its stranger, woolier negative mirror-image, the same-year adaptation of The Island of Dr. Moreau, also staring Kilmer, and both far messier and less invested in courting prestige cinema bonafides than exploring its loopier impulses. As an adaptation of a similarly Victorian fiction, let alone one which explores similar themes about Western egocentrism, Moreau is almost breathtakingly broken, whereas The Ghost and the Darkness’s messiness ultimately feels a bit deflating in its straightforwardness. It is both sturdily composed and reasonably thoughtful, whereas Moreau’s formal decisions lean in to and ravage its ability to work as a coherent text. (Consider Kilmer’s empty, stilted performance here compared to his absolutely deranged work in Moreau, for instance, and even then, he is outstaged by a nominally supporting player in both). Both films struggled mightily to get off the ground and were significantly altered from their original intentions. Yet the incompetencies and brokenness of Moreau reveal a certain diabolical appeal and cinematic madness that Ghost can only dream of.

Score: 5/10