Pursued is a Western noir where panoramic prospects are limned by opaque shadows, where even the idea of a landscape being available for a person to fasten their own future gives way to the gaping maw of the past ready to seek vengeance upon your every attempt. The preeminent Old Hollywood cinematographer James Wong Howe shoots the natural scenery of Gallup, New Mexico not with a hopeful Western’s sense of uncluttered expanse and possibility but, rather, a cloistered helplessness. A gloomy chiaroscuro contours the film’s moral perspective, figuring a shadowy backdrop for the story of a man beset from youth by histories far beyond his own abilities. Less overtly, the claustrophobic, closing-in-on-you texture of the visuals reveal a post-WWII nation whose abiding myths of natural possibility and individual capability were increasingly revealed to be lies. Pursued offers no blinding frontier of sublime possibility, only a dense effusion of subterfuge. Its characters are governed by forces they cannot even envision, subject to decades-long debts they cannot even name.

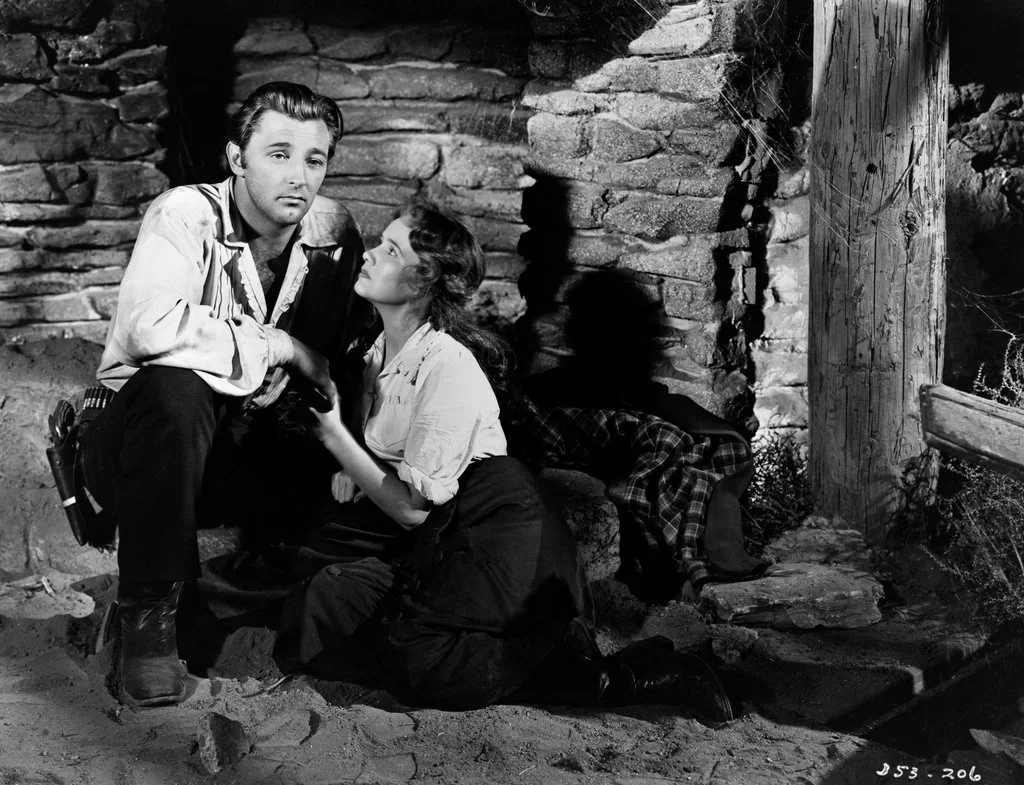

Early in Pursued, a brutal tragedy shatters a child’s psyche, conveyed to him in flashes of ambiguous stirrups and gun-shots from uncertain angles. From a more omniscient perspective, we know that young Jeb Rand, who will be played by Robert Mitchum as an adult, is the only survivor of a family massacre perpetuated by the vindictive Grant Callum (Dean Jagger). Grant relents not out of mercy or kindness but, only, seemingly, for the opportunity to prove that his wrath is transhistorical, that even the passage of many years cannot abate the retribution he feels is more a matter of cosmic principle than personal vendetta. In the interim, Jeb is taken in by Grant’s sister-in-law Mrs. Callum (Judith Anderson), who has two children, Thorley “Thor” Callum (eventually played by Teresa Wright as an adult) and Adam Callum (John Rodney as an adult), of her own. Meanwhile, Grant Callum plots from the shadows.

Twenty years later, Jeb can only remember a faint flicker of his childhood loss, and although he knows that he is not by birth a Callum, the harmonious workings of the ranch he operates with his adopted brethren more than approximate a loving family twenty-odd years later. Yet, beneath the genuine bonds of affection lie a thousand mostly unstated frustrations. Jeb, we gather, perennially itches at the scratch of his history, dimly reckoning that his life is caught up in the stories of others – his birth parents, for one – he remains unaware of, and Mother Callum keeps a tight lip on the incident that brought them together. Knowing they are not related by blood, Thorley and Jeb clearly have a more complex, but for the moment unclarifiable, relationship than “brother” and “sister,” and Adam clearly fancies himself the real “man” of the ranch. The obvious tensions, though, are mostly kept at a simmer by the comforts of family life, by obvious love and affection for all parties, and by the necessity of keeping the ranch running, that is until the Spanish-American War breaks out and one of the two brothers must join up. When Jeb “loses” the coin toss and comes back a war hero, Adam is clearly irritated at the years of unceremonious toil he has weathered back at the ranch, particularly when Grant starts ingratiating himself into their lives again and turning brother against brother.

That makes it sound like the film’s principal conflict is between Jeb and Adam, this is a full-family story, and Thor and Ms. Callum’s own feelings toward Jeb will expand and contract throughout the film. When Jeb hands Thor a tray of ceremonial wedding wine with a secret gun for her to use under a napkin, while she herself already has a gun behind her, the tragedy registers a distinctly mid-century sense of history having caught up with the hope of futurity, of people wrestling with a world truly beyond their control. Jeb himself is coerced to make tragic choices by others who will not back down, decisions (or reactions) that the forces of history have conspired to place on his gun and the guns of others pointed at him. Not that this is nihilistic denial of possibility, but it is telling that the final ethical conundrum is resolved not via heroic moral action on Jeb’s part, but to Mrs. Callum’s moral refusal to participate in the historical forces that have conscripted her into a tragedy not of her own making.

Through arranging nearly every single permutation of confrontation between the aforementioned characters you can imagine, Pursued manages the truly special trick of turning the seemingly ineffable into the truly unavoidable. While the nature of the conflict changes seemingly a half dozen times in Pursued – the film almost seems like a spring compression of a tall-tale, something that today would be expanded, and more than likely reduced via over-explanation, into an eight hour mini-series – every shift carries the crushing weight of inevitability on its heels. Every wrinkle feels like the machinations of a cruel destiny playing a trick on everyone involved, as the film grapples with characters who can only dimly reckon with being caught-up in webs and knots far beyond their own personal vision. “Some lost and awful thing come over me again,” Jeb remarks at one point, and Pursued is a film where the hopeful terror of sheer chance meets the terrifying hope of eternal return and nothing beyond mere, unabated repetition. It is a film where every frisson of the unexpected, every sidle into a new perspective on the conflict, ties the lasso around its characters necks even tighter.

Score: 8/10