Race, and America’s history of racial discrimination, suffuses every nook and cranny of To Sleep with Anger, but it is never “about” race per-se. In fact, Burnett’s film isn’t “about” any one theme in particular. Its ambiguous textures and lived rhythms are too finely observed to be pigeonholed, or to avoid the necessary complexities of the social tapestry that ever-presently shapes but does not define the lives of its characters. To Sleep with Anger percolates with micro-textures and minuscule gestures, all of which weave into a panoply of lived experience. It reckons with numerous wider structures that inform the world it inhabits, but it doesn’t feel the need to overtly manifest them in order to artificially demarcate its own contours or to map how we are supposed to read the film.

Burnett’s film opens with a startling intermixture, not only of quotidian naturalism and oneiric speculation but middle-aged comfort and undercurrents of disruption. As the patriarch of a Los Angeles African American family Gideon (Paul Butler) sits in a church, the camera panning to an apple slowly browning that soon catches fire. The apple browning echoes a similar opening by David Lynch in Blue Velvet, but rather than a manicured lawn revealing a swirling maelstrom of inner uncertainty, a cosmic chaos dormant beneath the ostensible placidity of order, To Sleep with Anger radiates a quieter but no less pressing ambivalence. The intersection of domesticity and spirituality promises order and stability, but silent screams are never far beneath.

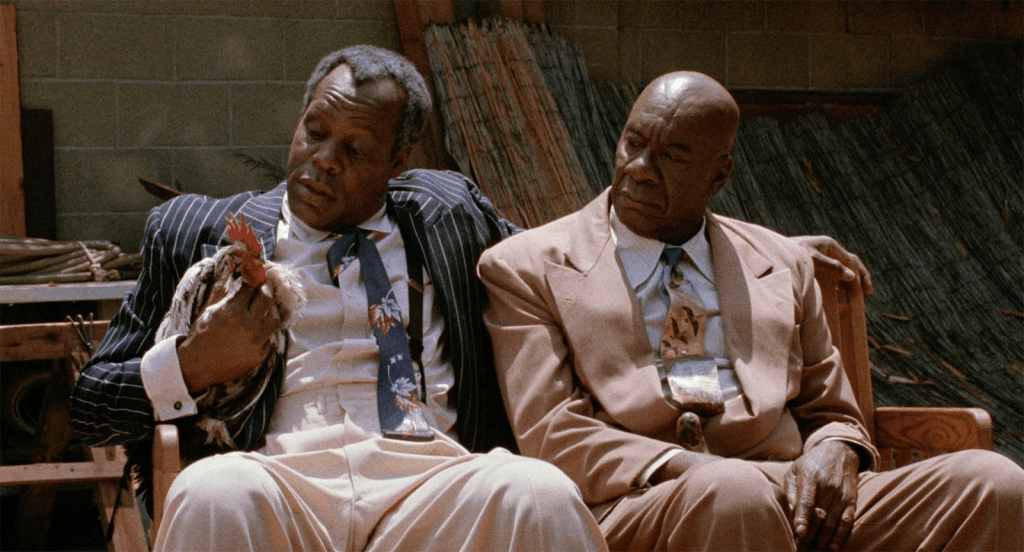

Gideon is married to Suzy (Mary Alice), a happily married, aging couple living in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles whose lives are both excited and agitated by Harry (Danny Glover), an old friend from the U.S. South who unexpectedly arrives on their doorstep after years of apparent non-communication. Welcomed with open arms, Harry soon emerges as a deeply ambivalent marker of the past’s hold on the present. He offers loose camaraderie and familiarity, but he also sows discord, between Gideon and Suzy’s adult children Junior (Carl Lumbly), who is married to Pat (Vonetta McGee) and who follows Gideon’s Christianity, and Babe Brother (Richard Brooks), who is married to Linda (Sheryl Lee Ralph) and who is more easily attracted to Harry’s ingratiating disobedience and pleasurable disturbances.

Harry is the paradigmatic trickster figure, both a rascally specter and a live-wire energy circuit, a living embodiment of cultural memory and an interruptive force. A walking revenant, he carries the past like the wind even as he catalyzes an uncertain future. “The devil,” writes Zora Neale Hurston, is one of the greatest “folk heroes” in Southern African American folklore because he knows how to survive and trick, to read into the gaps in people’s moralities, and to turn every moment into a space of possibility while appreciating the essentially confusing and contingent nature of everyday existence. Harry is no moralist, even if he feigns to be one at times. But he’s also a deeply suspicious man, who immediately worries that Gideon’s grandson Sunny (DeVaughn Nixon) may be immune to his charms and able to fell him when he brushes his shoe.

In 1990, Danny Glover was certainly most famous for his role in Lethal Weapon, an interracial buddy cop film that preserves the illusion of American possibility over-and-against “un-American” forces of corruption and explicit racism, emblematized in the South African villains of the film’s first sequel (a claim that scholars like Ed Guerrero and Michael Boyce Gillespie both make). Contrarily, To Sleep with Anger turns inward to intra-black relationships, exposing the complexity of mutual life, of people who are neither entirely defined by material struggle nor doing especially well but seem, essentially, content with their position in life even as anxieties hover. While Burnett’s spellbinding 1977 classic Killer of Sheep is a solemn moan, To Sleep with Anger is sly grin. The house at the center of To Sleep with Anger, as in Killer of Sheep, is only tenuously owned, but the texture of that fragility is very different from Sheep’s. While the earlier film laments a lack of personal security, To Sleep with Anger radiates communal friction and collective relation. The kitchen in Killer of Sheep is a space of frailty and frustration hiding subcutaneous particles of possibility, but the flow has been reversed in Anger, where the house is a space of openness and receptivity to movement and migration. There’s a comfort with discomfort here, a kind of appreciation for the house not as a prison but a liminal space where people come and go, show up and leave, linger and connect, where many feelings and sensations prismatically interpenetrate and no one emotion or sensibility predominates.

Of course, even this playfulness and openness to openness is nervously inverted in one of the film’s final jokes, when a corpse remains trapped on the floor long after it would have been removed by the police in a white house, as one character remarks. Throughout, Burnett wryly turns places of prospect and hope into regions of instability and potential loss. In one of the most spellbinding, and pivotal, moments, Harry and Gideon share a walk along train tracks, a paradigmatic liminal space where people come and go, where movement and stasis meet. Lynne Kirby calls films and trains “joke spaces” where identities could be donned and traded, connections could be foiled and foisted, and where capital’s relations were both occluded and revealed. Yet African Americans both worked the railways, and many porters – “psychologists” of the everyday, needing to read the desires and expressions of their white customers, as Malcolm X writes – utilized cunning and guile to survive the power dynamics of Jim Crow. Seeming momentum and possibility also occlude forms of oppression. Play can hide, even metabolize, particularly slippery modes of control. Harry, who thrives on knowing how, and on what terms, to be seen, is a master of these ambivalent zones. It’s not for nothing that he is first glimpsed as a shadow.

“You had to know your place” in the South, remarks Harry, evidencing a kind of reminiscence for the past – sometimes called “Jim Crow nostalgia” – even as this “knowing his place” evidently allows him to move and maneuver into and around people’s expectations, to occupy multiple places at once. This singularly evasive figure knows where he stands, how he is viewed, and how to mobilize it for his purposes, but the film’s view of him is equivocal. During their walk, Gideon glimpses another shadow of a black worker, who also built the railways, a memory of the past that lasts, a body violently subjected to perpetual, repetitive, limited motion in service of making capital move. The trip to the liminal space between past and present sets in motion a transformation, an illness for Gideon that only seems to recover from with Harry’s eventual passing. Harry himself is deeply, deviously fringe, a constellation of flows and energies, enigmas and opacities, meanings and mentions, an off-center rhythm that finds its own complement in the pestering trumpet player next door who evokes the minutiae of everyday growth as mutual irritation. He isn’t going away from the characters’ lives, the film implies, and he indexes a remarkably thorny series of conundrums and questions about the value of having one’s life unsettled by the relation between historicity and growth. How, the film asks, will they live with this conundrum, if not by exploring it together?

Score: 10/10