In honor of Black History Month, I’ll be reviewing a few of my favorite films about African American life. Because I’ve mostly been reviewing horror films of late, I figured the first might as well be the greatest work of Black horror.

The ostensible protagonist of Ganja & Hess is Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones), a wealthy archaeologist and art historian who both specializes in and collects African art. But the focal point is writer-director Bill Gunn, who appears in the film as Green’s depressed assistant George Meda. Unlike Green, who cultivates a manicured detachment and seldom seems to rise above the level of his own aesthetic distance, Gunn’s Meda is an open wound of a human being. While Green is cold, Meda is timorously alive and receptive to the complexities of the world, to the tensions of existence, to the haunting forces and figurations that encircle the living and press on us. Ganja & Hess is a film for him, and by him, a gaping maw of a creative work that opaquely weaves its way in circles around us and burrows its way into our souls.

Gunn’s is a strange, bedeviling film, a living embodiment of the phrase “gesture destroys concept,” spoken by Meda early on. It constantly slips and slides around meaning, accreting in fragments and figments, glances and evocations. While we glean that Hess becomes a vampire of a sort, it hardly seems to make an impression on the man who always-already seemed to surround himself with mementos of the dead. Not only is vampirism itself never mentioned in dialogue, but the feeling barely rises above the level of a curiosity for Hess, who mostly continues living his life as he always did, for whom vampirism simply is an extension of his material positionality. The whole film exists in a drugged-out, murky haze, filled with characters who seem vaguely aware that something ails them but either can’t quite make it out or simply don’t exert enough effort to care. I wrote that this is Meda’s film, but it’s really more like watching Meda try desperately to gnaw his way out of Hess’s

After stabbing Green with a ceremonial dagger he has been studying, Meda commits suicide. When Green finds the body, he also discovers that he has been infected with an insatiable craving to feed on the life of others that doubles as a seemingly obvious metaphor: as an academic, Hess exsanguinates the vitality and energy of black art by curating it as a backdrop for his apparently immense wealth. At one moment, he walks around outside in a fugue as Meda sits, top-half out of frame, on a tree, a noose that Green keeps hovering in front of both, hanging down from the tree. It’s his tree, and his noose, Hess remarks, and if Meda harms himself – if another black person “washes up” around his rich neighborhood outside New York City – Green is sure to be the one asked about it. Hess has cultivated his blackness as a bulwark against encroachment by the collective, and he seems to have devoured himself, inoculated himself against critique and exploration by other people, black or white.

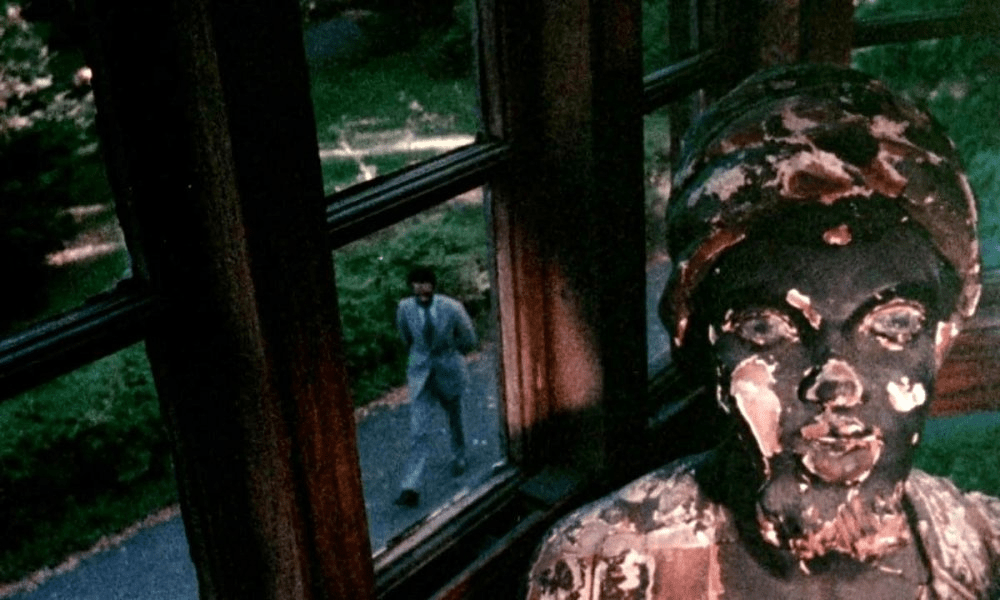

Except Gunn, of course. Throughout, we periodically glide through Last Year at Marienbad-style hallways where seemingly non-diegetic white guys with masks stalk, perhaps corporate overlords peering into the film from outside its frame, forces that exist outside the film’s purview. These figures exert no narrative energy, existing outside the logic of cause and effect., spectral presences that seem to watch over the film, ready to judge it or contour it. For Gunn, a playwright and struggling actor who was notionally tasked with making a Blaxploitation film or a Blacula companion piece, the presences register pangs of personal frustration. The film suggests a personal lament for the position of the African American artist in the early 1970s (and today), implying the living death of a man whose academic position is validated only as a translator and legitimizer of historical art within an anthropological frame. At one point, Green walks away from a camera which simultaneously seems to zoom in to follow him and to flatten him, as though he is bleeding into the frame itself, reduced from human to art object. When we cut to one of his statues in the next shot, we wonder if he’s become another object housed in his collection. And we wonder if, in inspecting Green, Gunn is also trembling at the pressures he faces, pondering what he might become, asking what the possibilities of his own film are, what role he might be relegated to.

Gunn’s film is equally wild and weary, elliptical and deeply opaque but also spontaneous and lively, hovering spectrally around a theme that it can’t quite make manifest. At one point, Green gets dressed after enervating a fresh kill (who we’ve never seen before), and the camera begins to tilt and tease Hess as though attempting to pierce his ego. Yet Green is placid, a negative fount of controlled inner chaos the film seems to want to stoke. The only one who can is Ganja (Marlene Clark), Meda’s lover who shows up at Hess’s door asking about her missing husband and receiving analytical and ethereal answers. An immediate connection forms between them for intuitive rather than logical reasons. After Ganja discovers Meda’s body, she is shot through a series of candelabras that attempt to deny her but fail to disguise her penetrating gaze, perhaps the only thing that might be able to faze the man.

Within Gunn’s cinema, like the cinema of so many other under-appreciated black auteurs, lies the possibility that black art might be a freewheeling irritant and a devious and mischievous exploration we are invited into, not a series of objects to categorize and curate but a field of play. Following Black Studies scholar Fred Moten, we could call it an interruptive frequency, an ongoing disturbance of a sort that demands a form of critique that wounds and disorients us more than we might penetrate it. Hess eventually seems to find a solidification, a solution, in Western religion, turning from pagan satisfaction to Christian penance. Yet the film’s psychic tremors persist in Ganja, who lives free of the strictures of guilt, who exists comfortably with the art of self-transformation, with a view of the self as becoming rather than being, as a resonance that takes in and gives off various fluctuating energies but is not beholden to them. Ganja and Hess is an iridescent gem worthy of Altman’s McCabe & Ms. Miller and a malevolent force worthy of Argento’s Suspiria. The film radiates a relationship to black desire that is complex rather than simple, sensual rather than categorical, sublime rather than knowable.

Score: 10/10