A shivering man (Joe Morton) lands on Ellis Island. We pan down to see that he is missing a foot. An interstellar fugitive from a chain gang, to use a metaphor the film will draw on later, the man is lost and lonely but also strangely filled with potential. When he bends down to take care of the wound, there’s a new foot there, albeit with three toes. Cinematographer Ernest R. Dickerson, in his second film after his student film with Spike Lee Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbership: We Cut Heads (and before a lucrative further decade with Lee) shoots Morton with a gorgeous, crepuscular glow that weaves an inextricably cinematic spell, an iridescent halo seeming to illuminate him. The film offers a play of light and shadow that invites us in but allows Morton to remain somewhat obscure and impenetrable to us, even as the film will go on to meditate on the ability of this wayward traveler to vibrate with the world around him, to connect more deeply than we may be able to and in spite of the odds being stacked against him. Already, within minutes, we have an enigma that is far deeper than any superficial narrative mystery to be successively doled out in pieces by the filmmakers: what does it mean to find connection within and via alienation? As the film unfurls, filmmaker John Sayles conjures and concocts a whimsical meditation on cosmic loneliness that becomes an exploration of local togetherness.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: February 2024

Midnight Screamings: Cronos

Guillermo Del Toro’s pet fascinations seem to have emerged almost fully formed in Cronos, his debut feature. Despite its less ostentatious sensibility, this is very much the work of the man who would make Pan’s Labyrinth. But it is no mere prologue. While Del Toro’s later films lather on either special effects or themes which increasingly seem like special effects, they also risk monumentalizing themselves. Despite its eminent craft, Pan’s Labyrinth feels like less than the sum of its parts nearly two decades on, as though it might collapse under the weight of the themes that signal its importance and the somewhat overworked narrative parallels that strive for conceptual relevance. Perhaps it spoke to its moment, but it also feels too strained to work as anything more than an antique to a particular flavor of Oscarbait cinema. And that’s saying nothing of his actual Oscarbait picture, the nearly somnambulant The Shape of Water.

Pan’s Labyrinth might have learned from a thing or two from Del Toro’s first film, in that regard. For all its resonance, Cronos is a decidedly spry, suggestive affair, never taking three metaphors to say what a brief glance or a hesitating pause might reveal. Indeed, the actual metaphor of the film is somewhat opaque, slowly – and without any obvious “twist” – sauntering into a slantwise vampire story rather than plunging in from the beginning. Jesus Gris (Federico Luppi), the protagonist of Cronos runs an antique shop, until he is “bitten” by one of his antiques. Suddenly, slowly afflicted with an almost-unstated craving for blood, the film plays loose with vampire mythology, but it is very much Del Toro’s exploration of the craving for infinite life that turns the body itself into a deadened machine. As one character says of his rich uncle’s desire to find the creature, “all he does is shit and piss all day and he wants to live longer?” That the wealthy uncle De La Guardia (Claudio Brook) hardly figures in the film, and that his conniving nephew Angel (Ron Perlman) who hardly cares about the metaphysics of lineage and simply wants to succeed, ends up figuring as a more central villain says something about Cronos’s general vibe, its appreciation for the deflationary and the quasi-comic, the gesture that undercuts even in the act of incanting.

Released during the nadir of horror cinema as a popular and creative outlet, the early 1990s, when the decade was still in the midst of withdrawal from the slasher film high that quickly turned into an addiction, Cronos slips its fang into the moribund genre’s neck to reveal subliminal life.The creature itself is a clockwork insect, a vampiric inversion of the mechanical and the organic that suggests pulsing life dormant beneath objects that might be curated and controlled for display. The desire eternity is an inhumane way of absolving oneself from the complexities of existence, the film suggests. Rather than hiding death under life’s mask, as most vampire films do, Del Toro finds life dormant in an emblem of machinery, a golden antique that suggests a grotesque parody of immortal life encased in an armor of riches.One can trace the tendrils to Del Toro’s recent magisterial Pinocchio, which certainly portends his upcoming version of Frankenstein, another story of a modern Prometheus in search of transcendence who only discovers his own inability to cope.

That could also be a metaphor for the film itself. This deceptively simple story of the boundaries of life and the limits of death is all the more touching for how surreptitiously and even straightforwardly it leeches thematic resonance out of its story-world, how casually it feels attuned to everyday rhythms and, well, life. Indeed, life masking death is an unfortunately apt description for several of Del Toro’s later films, which too often seem frisky and deranged but ultimately reveal hollow cores (although his Pinocchio is a peach). Vaguely pleasing though it is to watch Del Toro given 100 or even 200 million dollars to aestheticize the lingering traces of our pasts, Cronos alone feels alive to its present. When Jesus gets his first taste of blood in the bathroom at a party, an angry partygoer wipes it up from the counter, leading an undeterred Jesus to lap up what little remains the floor, a moment that radiates even more lethargic sadness due to its casually offhanded manner. When a shoe walks past him, it briefly registers as a comment on the casually uncaring cruelty of the wealthy before it returns to the labors of the story-world. Crimson Peak, with its gothic manse literally sitting atop a field of blood-red dye, a gloriously baroque image that is also a crudely pandering, if amusingly self-amused, metaphor, ain’t got nothing on this tiny pool of blood and one man’s sudden, insatiable craving for it.

All of Cronos’s best moments are quietly insinuating like this, morbid incisions of quiet, quirky malevolence rather than meat-cleavers of meaning. After the “villain” Angel (Ron Perlman) attempts to murder Jesus without recognizing the implications of his affliction, Del Toro lovingly lingers on the work of a morgue attendant preparing the body for a funeral that never arrives. “It’s your best work yet,” he’s told, to which the attendant responds, lovingly exploring the nooks and crannies of the corpse, that there is “a technique to this. I’m giving it shape, texture, color. You have to be a fucking artist.” Del Toro gives himself the perfect metaphor for his own career, and then immediately mocks it. The widow has decided to cremate. Some people, Del Toro muses, just don’t appreciate the craft of death, and the of art of life.

Score: 8/10

Midnight Screamings: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Francis Ford Coppola’s deliriously remarkable Grand Guignol version of Dracula, released in 1992, reminds me of Alice in Chains’s seminal muck-spreader of an album Dirt from the same year. In both cases, my love for the object doesn’t always defray the disquiet I feel about the damage it wrecked on its medium. Fortunately, while Dirt and its ilk turned rock music into a no man’s land of post-grunge for nearly a decade, Dracula merely took a genre that was already in the grave and dressed its corpse in Victorian duds. The success of Coppola’s film clearly gave Hollywood a reason to “class up” the old-school Universal Horror monsters as an Oscar-approved variant of the genre. Buttressed by the simultaneous success of Merchant Ivory British period epics like Howards End, the resulting monster movies ultimately traded in indulgences of the demonic for pretensions of the divine.

Divine, of course, means respectable, which, for a horror film, means death. While Coppola’s Dracula is a truly unhinged, discombobulated work, and Mike Nichols’s Wolf, while less than fully compelling, nonetheless attempts its own spin on the wolfman archetype, Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein benefits and suffers alike from its obvious zeal for the material. While it has the eager-to-please smile of an ‘80s horror film, it also has the buttoned-up, primed-and-polished straightness of a prestige period piece. It treats the material worshipfully, as holy writ to study or a monument to bow down before, and in doing so it ironically exsanguinates its devilish spirit. This is a distressingly, unimaginatively literal work, yet it absolutely lacks the texture of the original work itself. In following the letter, it kills the spirit.

The grunge comparison I opened with isn’t just incidental either. Branagh clearly adores himself as always, and that shows both in front of and behind the camera. Running around as the protagonist, he saunters and flagellates like a rock star lost in 18th century England. His direction is consummate, but, as per usual, his visual and actorly showboating extend beyond loving into the somewhat grotesquely self-aggrandizing. As he would do decades later with Hercule Poirot, another cherished literary character, he accents the soulful and compassionate tendencies of the figure at the expense of their angular and distorted features or their capacity to reveal wider social tensions. Rather than being pock-marked and then riven by societal tensions they can’t help but embody, they beautifully – banally – peer into them from a moral high ground. Branagh himself stares longingly and broodingly before the camera, but this particular film lacks enough familiarity with death to truly bring itself to life. When Branagh first announces himself, the film pauses for several seconds after “Victor,” as though the camera has been waiting with one hand in its pants for the title to drop.

Branagh is, as he always is, trying exceptionally hard to convince us that he is an honest to God film director – at one point, we even get a half-rate imitation of the famous Lawrence of Arabia graphic match – but the effects are more deadening than electrifying. The camera pirouettes and cavorts in semi-comic circles to evoke the giddy high of scientific exploration but has little visual sense for the character’s manic derangement or the lingering tensions of Frankenstein’s ego. Branagh reduces a torrent of societal anxieties and energies to an essentially personal conundrum and an individualized tragedy, producing a dangerously myopic adaptation that fetishizes the hero’s body without much to say about his mind. Themes are there, lingering in the shadows. Even the concept suggests a connection between maestro and scientist and film director that travels all the way back to the roots of cinema itself, often described as a “Frankensteinian” technology with aspirations to assemble shots of dead history into renewed collective life. But Branagh establishes these connections passively, not as a matter of intent but a simple fact of cinematic existence. He simply can’t but indulge himself, and it feels like he’s showing off rather than honing in or letting loose. This marks him as a genuine auteur of a kind. It also reminds us that being an auteur is in no way a marker of being an artist.

Score: 5/10

Film Favorites: 8 1/2

The famous opening of Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ visualizes auteurism – the notion that a director is an Olympian artist singularly responsible for their film – as a psychic and cosmic trap, a road to nowhere as everyone around watches you suffocate. They’re immobile, unhelpful figures in a dreamlike haze trapped in the Gorgon’s glare. Of course, as the film finally reminds us, if Medusa is a metaphor for the world’s horrors (as Siegfried Krakauer famously notes in his 1960 text Theory of Film, just a few years before Fellini’s film) and art is Perseus’s shield allowing us to glimpse the horror and move beyond it. But Fellini insists that art itself can also immobilize. In 8 ½, it is the director himself who won’t let the world and its people move. They can’t help him because he isn’t receptive to their energies. That the film itself amounts to both a validation and an excoriation of its own inability to heed those energies is, depending on your view, its central failing or its greatest success. 8 ½ is a masterful work, no doubt, but it’s also a grand-standing testament to artistic mastery as a form of artistic limitation. Personal responses may vary.

The auteur in question is Guido Anselmi (Marcelo Mastroianni), who we meet in the middle of a bout of director’s block on a film that has already had a rocket-ship of money poured into it, but has no screenplay. Guido is both an aspirational portrait of a director as ringmaster and channeler of the world’s energies and a tacit admission of guilt on Fellini’s part. He remains too caught up in his own ego to, as it were, release, too lost in his thoughts to let the film really feel. It takes a certain amount of chutzpah to make us spend 140 minutes, and to stake your directorial reputation, on an elaborate metaphor for erectile dysfunction.

Continue readingFilm Favorites: Head

At the beginning of Head, Monkees’ drummer Micky Dolenz runs away from a legion of fans and dives off a bridge into a body of water. If this is too-obviously following in the footsteps of its prankish predecessor, A Hard Day’s Night, where the Beatles suffered a similar crowd-sourced fate, it also blows it to smithereens. Rather than canonizing the ‘60s, Head offers a comeuppance, jumps into the deep end of the next decade, dissolving into an aqueous, collective, diffuse space called the early ‘70s.

Soon enough, the band performs the phenomenal, acid-stained rocker “Circle Sky,” a mission statement of the band’s newly serious attitude toward their music that ultimately unweaves itself in the very act of coming into being. If the song promises progress, a band achieving new heights of self-worth and self-ownership, the lyrics offer a vision of eternal return that culminates in fans rushing the stage only for the band to be crumble as mannequins, material constructs of composite parts, all image and no flesh. Rather than personal authenticity, the film explodes into gleeful mediation, a promise that ostensible freedom only masks new modes of control, that genuine originality is only one more mask. Head marked the band announcing their recovery of their own catalogue as an exercise in self-becoming, and in doing so they paradoxically destroy themselves. We’re off to the race in the opening minutes, in other words, but we’re also lost in an abyss. In the band’s go-for-broke stylistic tour-de-force, they go beyond playful monkeying around and instead monkey wrench the nuts and bolts of the machine that made them.

Continue readingBlack History Month: To Sleep with Anger

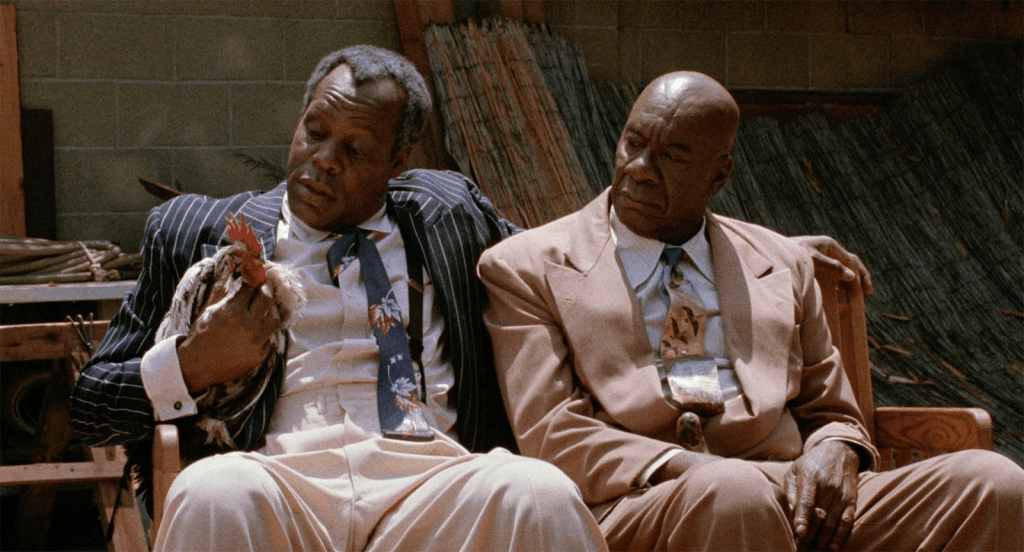

Race, and America’s history of racial discrimination, suffuses every nook and cranny of To Sleep with Anger, but it is never “about” race per-se. In fact, Burnett’s film isn’t “about” any one theme in particular. Its ambiguous textures and lived rhythms are too finely observed to be pigeonholed, or to avoid the necessary complexities of the social tapestry that ever-presently shapes but does not define the lives of its characters. To Sleep with Anger percolates with micro-textures and minuscule gestures, all of which weave into a panoply of lived experience. It reckons with numerous wider structures that inform the world it inhabits, but it doesn’t feel the need to overtly manifest them in order to artificially demarcate its own contours or to map how we are supposed to read the film.

Burnett’s film opens with a startling intermixture, not only of quotidian naturalism and oneiric speculation but middle-aged comfort and undercurrents of disruption. As the patriarch of a Los Angeles African American family Gideon (Paul Butler) sits in a church, the camera panning to an apple slowly browning that soon catches fire. The apple browning echoes a similar opening by David Lynch in Blue Velvet, but rather than a manicured lawn revealing a swirling maelstrom of inner uncertainty, a cosmic chaos dormant beneath the ostensible placidity of order, To Sleep with Anger radiates a quieter but no less pressing ambivalence. The intersection of domesticity and spirituality promises order and stability, but silent screams are never far beneath.

Continue readingBlack History Horror: Ganja & Hess

In honor of Black History Month, I’ll be reviewing a few of my favorite films about African American life. Because I’ve mostly been reviewing horror films of late, I figured the first might as well be the greatest work of Black horror.

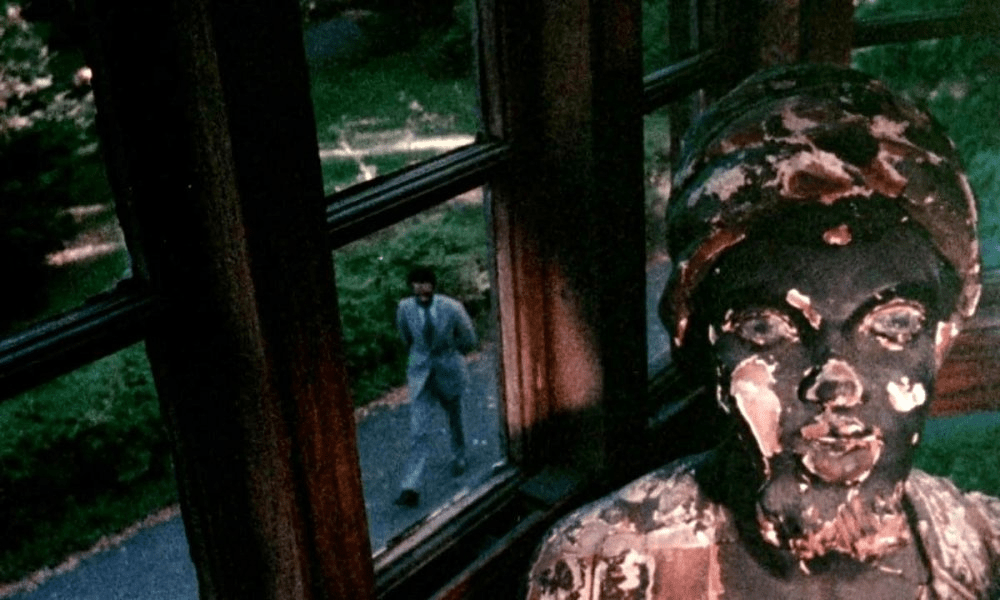

The ostensible protagonist of Ganja & Hess is Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones), a wealthy archaeologist and art historian who both specializes in and collects African art. But the focal point is writer-director Bill Gunn, who appears in the film as Green’s depressed assistant George Meda. Unlike Green, who cultivates a manicured detachment and seldom seems to rise above the level of his own aesthetic distance, Gunn’s Meda is an open wound of a human being. While Green is cold, Meda is timorously alive and receptive to the complexities of the world, to the tensions of existence, to the haunting forces and figurations that encircle the living and press on us. Ganja & Hess is a film for him, and by him, a gaping maw of a creative work that opaquely weaves its way in circles around us and burrows its way into our souls.

Gunn’s is a strange, bedeviling film, a living embodiment of the phrase “gesture destroys concept,” spoken by Meda early on. It constantly slips and slides around meaning, accreting in fragments and figments, glances and evocations. While we glean that Hess becomes a vampire of a sort, it hardly seems to make an impression on the man who always-already seemed to surround himself with mementos of the dead. Not only is vampirism itself never mentioned in dialogue, but the feeling barely rises above the level of a curiosity for Hess, who mostly continues living his life as he always did, for whom vampirism simply is an extension of his material positionality. The whole film exists in a drugged-out, murky haze, filled with characters who seem vaguely aware that something ails them but either can’t quite make it out or simply don’t exert enough effort to care. I wrote that this is Meda’s film, but it’s really more like watching Meda try desperately to gnaw his way out of Hess’s

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II

Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II is a thoroughly slantwise sequel. Rather than honoring its predecessor, it merrily runs amok with it. Insofar, that is, as it is interested in the first Prom Night at all. That 1980 film was a first-generation slasher film, released when the genre was not so much figuring itself out as already dying a premature death in the womb. Creatively speaking, at least. Slasher films would continue to thrive in the box office for several years, but the genre was commercially on the way out by 1987, when this sequel was released. While many slasher films were still being released every year, horror cinema was on its way to the grave for the first half of the 1990s, before a revival closer to the turn of the century. Prom Night II treats the slasher era’s wilderness years as a real wilderness, living out a creative hunger to survive just by attempting anything at all. It is liberated, after a fashion, by the genre’s own demise, as though the relief of recognizing its own poor box office prospects allowed it to explore its own inner urges without apprehension.

Which isn’t to say that the film doesn’t have its finger on the pulse. Hello Mary Lou joins John Carpenter’s 1983 killer car picture Christine in excoriating its decade’s obsession with the 1950s, manifesting the Reagan era’s fetishistic fixation on its forebears as a literal possession by a dormant specter. That said, the film’s visual and sonic cues are hardly limited to, or even primarily defined by, ‘50s cues. If this film has a closer aesthetic analogue, it’s Kenneth Anger’s gleefully perverse explosions of mid-century teenage iconography. Although shorn of Anger’s wry recognition of mid-century American fascism, Hello Mary Lou similarly recognizes the paradox of turning to one’s ancestors for a portrait of youth and rebellion. And it similarly plays critique with a frisky grin rather than a moral scold.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Mad Love

Historian W. Scott Poole makes a potent case for the 1924 film The Hands of Orlac as an aftershock of World War I. Reflecting the psychic tremors of a battle where bodies and minds were warped and destroyed, humans reduced to automatons and warped into psychological and physical pieces, the 1924 film severed a pianist’s hands and depicted the terror of the body seemingly working at odds from the mind that was supposed to control them. The 1924 film was directed by Robert Wiene and starred Conrad Veidt (both of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari a few years beforehand), perhaps the first burst of Hollywood engagement with German Expressionist shadowplay, the surest throughline between Weimar horrors and the rise of the Universal Horror Monsters that would cast a long pall on horror cinema. Perhaps aware that it could all-too easily be seen as an also-ran, 1935’s Mad Love is a nominal remake thatreframes the story entirely. If The Hands of Orlac laments the violence of returning soldiers, Mad Love is very much about those who never went to war, for whom the war was a theater to watch and, perhaps, violently obsess over.

While the original story focuses on the plight of talented pianist Stephen Orlac (played, in this 1935 version, by Colin Clive), who loses his hands in a train accident and has them replaced with a murderer’s (Rollo, here played by Edward Brophy), this version shifts to Peter Lorre’s Dr. Gogol (Peter Lorre), the doctor who performs the operation and is infatuated with the pianist’s wife Yvonne Orlac (Frances Drake). Gogol, who houses a mannequin of Yvonne, fancies her Galatea to his Pygmalion, borrowing from the Greek play about an artist that conjures their sculpture to life via sheer artistic ability infused with the incantatory potency of desire. This last dynamic marks Mad Love as a deeply tormented meditation on the relation between creation and control. Rather than a performer-soldier, Gogol is a tragic mastermind-director, longing for something he can only domineer from behind the scenes.

Continue readingMidnight Screamings: Q: The Winged Serpent

In Larry Cohen’s Q: The Winged Serpent, Midtown Manhattan is being menaced by a giant bird-like dinosaur creature. That, incidentally, is not a good description of it, but it’s better than the verbal description given by the characters in the film. It also has something to do with a string of cult-like murders being investigated by Detective Shepard (David Carradine) and Sgt Powell (Richard Roundtree). It also crosses paths with Jimmy Quinn (Michael Moriarty), a failed pianist turned small time crook (now there’s a career path for you) who also seems to double as a bundle of raw nerves. None of these various menacings really cohere into anything actually menacing as a horror film, but Q’s strangenessmakes it exceedingly difficult to care about superficial things like a film’s genre or the temper it is supposed to have.

Much of that strangeness comes courtesy of the thing really menacing Midtown Manhattan in Q: Michael Moriarty, who seems to unravel the film as he passes through it. A walking psychic tremor of a man, Moriarty’s Jimmy is a human paradox who seems both deeply self-congratulatory and egotistical and essentially lost. He feels like a walking open wound of Method tics, a man feeling out his way through the world. The narrative itself – about a man who feels he has had no shot in the world and needs to command the momentary opportunity he has stumbled into, but doesn’t really know how to – reflects the performative style, which seems obsessed with controlling the space and the audience even as it is barely registering any effort. It’s a truly unmanicured performance, blistering with raw nervous energy and chaotic inner expressiveness. The most unsettling scene has nothing to do with the titular serpent but, rather, the camera’s own serpentine moves around Moriarty as he sidles up sinisterly to a piano less to tickle than prick the ivories on a frankly demented little ditty. It’s a remarkable scene, one in which the narrative content is essentially trivial but the form of the scene and its placement in the film evoke a much darker story.

Continue reading