Released at the tail end of a number of remakes of mid-century horror pictures, Chuck Russell’s The Blob often gets the short end of the remake stick. If the remake trend was the fruit of the decade’s fixation with recovering, or rather creating, a mid-century optimism, the 1988 The Blob was released at the end of the trend, on the cusp of Bush-era cynicism, and is usually considered an also-ran amongst the heavy hitters of the era’s remakes. Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Don Siegel’s 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers started the trend with a new version that updated that ultimate meditation on Eisenhower-era conformism into a critique of the failures of ‘70s individualism, the exsanguinating of the possibility of ‘60s liberation into a cult of mere personal difference. John Carpenter’s brutally poetic 1982 film The Thing recognizes and laments the fact that a group of men stranded and with even a little reason to worry are fundamentally willing to destroy one another. (His Christine one year later also turns mid-century iconography and masculinity into an auto-erotic death-drive and a failure to genuinely progress, but it is not a remake). David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986) refigures Frankenstein as a post-industrial blues for the neoliberal era and a striking meditation on the human mind overtaking and corrupting the human body.

The Blob is, arguably, the least essential of these films (I wouldn’t quibble with the claim), and the comparisons arguably invite expectations The Blob itself doesn’t have much interest in validating. Plus, it only slightly precedes the end of this remake cycle and the birth of a second round of remakes: Savini’s Night of the Living Dead (1990) and a third version of Invasion, simply titled Body Snatchers, anticipating a decade of ‘70s nostalgia. Nonetheless, The Blob does feel of a piece with these earlier films. It lacks Carpenter’s meditative sangfroid and Cronenberg’s psychosexual energies and exploratory fixation on the limits of the human body, but it is, in its own way, a terse and cunning quasi-satire of ‘80s-era cultural conformity. When the film begins, a phenomenally moody, empty town suggests a derelict, post-apocalyptic hellscape for several minutes before the film cannily reveals seemingly the town’s entire population at the local football game. The titular mass of metastacizing pink extraterrestrial goo, it seems, hardly needs to get to work. Small town life has already eaten itself alive.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Russell’s previous film was Nightmare on Elm Street 3, by far the best of the Nightmare sequels and arguably the best film in the series. The Blob nails the film’s peculiar mixture of danger, disfigurement, and droll wit, capturing the ethos of the only Freddie film where Freddie was both Bugs Bunny and genuine sadist. This is a nasty, even cruel film, but also a surprisingly morbid comedy. A mid-film screening of the hilariously named Friday the 13th rip-off Garden Tool Massacre (which, a kid ensures us, has no “sex” or “anything bad”) becomes the site of some of the film’s gnarliest encounters, when The Blob is, inevitably, let loose in that icon of mid-century Americana: the movie theater. The average slasher villain, trapped in a frail humanoid body and requiring cinema itself to legitimize their stalkings with manipulative musical accompaniment and, in Jason’s case, the distinctly cinematic capacity to jump locations, has nothing on this mutating mass of sheer ectoplasm, ready to take any form and become any metaphor you like. The Blob, with its all-consuming ability to engulf and evacuate any human specificity,revels in its destruction of small-town America with the most demented glee this side of Gremlins.

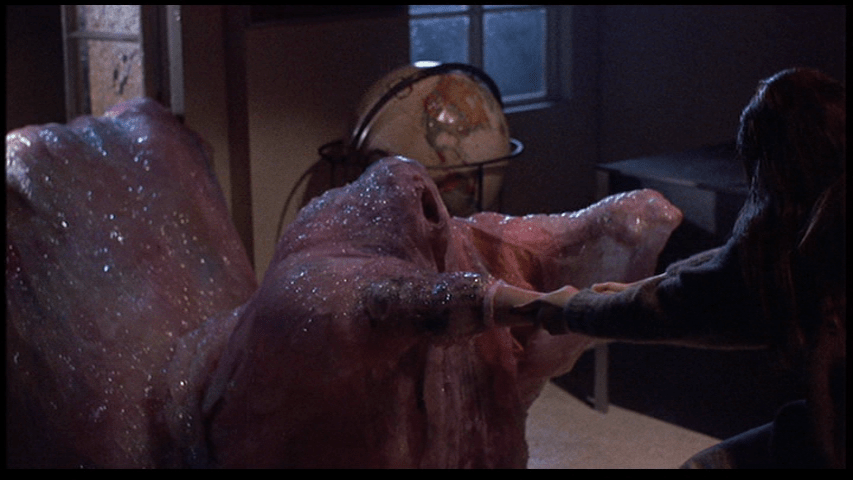

The first two-thirds, at least, are phenomenally constructed horror filmmaking with a mordant, dryly subversive undercurrent. The simply remarkable practical effects certainly help, creating the stickiest (both on the screen and in the brain) body deconstructing scenes of the decade this side of The Thing. In one truly cutting sequence, the presumable protagonist Paul (Donovan Leitch) is unceremoniously offed by the Blob that seems thrilled to remove the bland archetype from the film, leading to a violent parody of a lover’s handhold with his girlfriend Meg (Shawnee Smith), who now hooks up with third wheeler Brian (Kevin Dillon). Co-writers Russell and a (pre-King adaptation(s)) Frank Darabont clearly enjoy having a bigger budget than this material probably affords, one they perhaps inevitably could not recoup, but Tony Gardner’s killer decomposition make-up scenes are brutal beauties, arias of blood and bodily deconstruction worthy of the price of admission all on their lonesome. The last third of this (impeccably short) film get a little too big for their britches. Much as the titular creature itself is more frightening when it is smaller and able to slip through society’s cracks, the film loses its subversive texture in the impulse to grow larger and larger. But the first hour goes down like acid.

Score: 7.5/10