Disney Animation’s package films from the ‘40s, as a corpus, are sometimes considered the bane of the company’s existence, mercenary workaday productions inspired by a need to salvage the tatters of the company by producing anything that would make a buck, theoretically leaving their artistic inhibitions at the door. The ghetto these films have been sequestered into isn’t without purpose; compared to the brazen murderer’s row of artistic masterpieces released between 1940 and ’42 – Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, Bambi – one can see why no one is eager to pull, say, Saludos Amigos from 1942 out of the dustbin of history.

Disney Animation’s package films from the ‘40s, as a corpus, are sometimes considered the bane of the company’s existence, mercenary workaday productions inspired by a need to salvage the tatters of the company by producing anything that would make a buck, theoretically leaving their artistic inhibitions at the door. The ghetto these films have been sequestered into isn’t without purpose; compared to the brazen murderer’s row of artistic masterpieces released between 1940 and ’42 – Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, Bambi – one can see why no one is eager to pull, say, Saludos Amigos from 1942 out of the dustbin of history.

Nonetheless, the humbling failure of the corporation’s artistic endeavors (at least commercially) managed to sand down Walt Disney’s sometimes offputting enormity, freeing up some space for a few free-wheeling slivers of silliness and laying bare the lie that Disney’s lack of money during this era actually hindered their ambulatory creativity. While none of these films measure up to, say, Pinocchio or Fantasia (but what does?), the lesser efforts from the ‘40s are often reservoirs of loosened-up, slackened vigor owing largely to the more rambunctious, less ossified nature of the short stories that make up these tales. Little bursts of candy-coated joy rather than euphoric self-conscious masterpieces, many of the segments are ultimately ephemeral. But in ephemera, they locate an expedient, in-and-out mirthfulness woefully absent in many nominally larger motion pictures. Continue reading

In this ostensibly superficial, altogether dazzling production about three birds in Central and South America, Disney’s near-commercial implosion arises like an avian on fire in arguably the company’s most surrealistic insurrection. Trapped in the perdition of nonexistent budgets, Disney Animation went vagabond and took a trip to, and a cue or two from, the superstars at Termite Terrace (read: Looney Tunes) with a deliberately unfussy, anarchic production for which out-of-control effusions of rhapsodic color was the only reasonable aesthetic partner. Pointless though it seems, The Three Caballeros is in fact a vanguard of the company’s continued artistic experimentation and their hunger for something a little more allegro.

In this ostensibly superficial, altogether dazzling production about three birds in Central and South America, Disney’s near-commercial implosion arises like an avian on fire in arguably the company’s most surrealistic insurrection. Trapped in the perdition of nonexistent budgets, Disney Animation went vagabond and took a trip to, and a cue or two from, the superstars at Termite Terrace (read: Looney Tunes) with a deliberately unfussy, anarchic production for which out-of-control effusions of rhapsodic color was the only reasonable aesthetic partner. Pointless though it seems, The Three Caballeros is in fact a vanguard of the company’s continued artistic experimentation and their hunger for something a little more allegro.  At some off-in-the-distance eye-squint of a level, Suicide Squad files itself in the same phylum as Zack Snyder’s Watchmen, and not only because Snyder is now the spiritual guiding light of the DC Cinematic Universe (and assuredly had a hand in Suicide Squad, however clandestine that hand was). Both stake their identities on a liquid understanding of superhero morality, where goodness and badness are not essential, innate mantras but malleable clay to be sculpted by whatever entity chooses to. Except, while Watchmen donned the garb of “good guys as bad guys”, Suicide Squad bears witness to the inverse; tonally, it also proposes itself as the polar opposite, a rip-roaring, piratical B-picture, a vulgarization of Watchmen, which was a lugubrious, thematically portentous “take me seriously” A-picture. For Suicide Squad, vulgarization is the ideal. Vulgarity is no shame, unless you act ashamed of it, which is where the film buckles and the whole faux-blasphemous edifice crumbles, deflates, and ruptures. Rule-breaking though it seems, Suicide Squad bears exactly the narrative structure, and even the particulars, of a project conjured by a whole bunch of starch suits.

At some off-in-the-distance eye-squint of a level, Suicide Squad files itself in the same phylum as Zack Snyder’s Watchmen, and not only because Snyder is now the spiritual guiding light of the DC Cinematic Universe (and assuredly had a hand in Suicide Squad, however clandestine that hand was). Both stake their identities on a liquid understanding of superhero morality, where goodness and badness are not essential, innate mantras but malleable clay to be sculpted by whatever entity chooses to. Except, while Watchmen donned the garb of “good guys as bad guys”, Suicide Squad bears witness to the inverse; tonally, it also proposes itself as the polar opposite, a rip-roaring, piratical B-picture, a vulgarization of Watchmen, which was a lugubrious, thematically portentous “take me seriously” A-picture. For Suicide Squad, vulgarization is the ideal. Vulgarity is no shame, unless you act ashamed of it, which is where the film buckles and the whole faux-blasphemous edifice crumbles, deflates, and ruptures. Rule-breaking though it seems, Suicide Squad bears exactly the narrative structure, and even the particulars, of a project conjured by a whole bunch of starch suits.  Released at the onset of Disney’s so-called Silver Age, where the money began to flow again (incrementally) in the ‘50s after the box office disasters of the early ‘40s subjected Disney to a handful of no-budget package films throughout the war and post-war years, Alice in Wonderland was a fitting rekindling spirit. None other than Walt Disney’s own childhood love and his original plan for a first feature film before things got sidetracked (as they do in animation), Alice was ironically whisked away from a fell purgatory without Uncle Walt’s own influence (perhaps he’d grown weary over trying to produce it again and again over the years), and perhaps for the better. The patchy, maniacal disarray to the look of the film and the semi-unwholesome, deliberately non-moralizing grotesquerie of the structure weren’t exactly Walt’s specialties, but one wonders what countenance his version of the tale might have born. Maybe Alice would have been a young Margaret Thatcher, and the Mad Hatter a starched-suit Joseph McCarthy and the impromptu hero. Alas, I do not suspect even Walt could have any sensible use for the bundle-of-id that is the Cheshire Cat.

Released at the onset of Disney’s so-called Silver Age, where the money began to flow again (incrementally) in the ‘50s after the box office disasters of the early ‘40s subjected Disney to a handful of no-budget package films throughout the war and post-war years, Alice in Wonderland was a fitting rekindling spirit. None other than Walt Disney’s own childhood love and his original plan for a first feature film before things got sidetracked (as they do in animation), Alice was ironically whisked away from a fell purgatory without Uncle Walt’s own influence (perhaps he’d grown weary over trying to produce it again and again over the years), and perhaps for the better. The patchy, maniacal disarray to the look of the film and the semi-unwholesome, deliberately non-moralizing grotesquerie of the structure weren’t exactly Walt’s specialties, but one wonders what countenance his version of the tale might have born. Maybe Alice would have been a young Margaret Thatcher, and the Mad Hatter a starched-suit Joseph McCarthy and the impromptu hero. Alas, I do not suspect even Walt could have any sensible use for the bundle-of-id that is the Cheshire Cat.  The Emperor’s New Groove

The Emperor’s New Groove After his passion play exploded and perfected itself circa 1989 with the sublime muck-raking journalism of Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s inimitable style, while typically expressive, developed a tendency to crash into the realms of the expressly overwrought and the tangled, even by the standards of a polemicist. Qualms aside though, his films seldom dipped below the realm of inspiration, but that didn’t keep Lee from grasping for mainstream success. Pigeon-holed even though he didn’t deserve to be – his ‘90s output is a rainbow, a prism, of different, improbably variegated points of tonal and conceptual ingress to the subject of race – the ‘00s saw him on a vision quest for public acceptance, which unfortunately meant curtailing his polemical tendencies, excising race, or at least reducing it to the ghetto of the subliminal or implicit realm. The fruits of this shift were among his sharpest works – 25th Hour, Inside Man – but also among his more manicured and thus easily digestible, perhaps too judicious in their careful, almost ginger treatment of themes when Lee’s natural inclinations are for the dangerous.

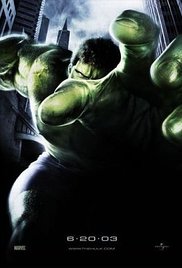

After his passion play exploded and perfected itself circa 1989 with the sublime muck-raking journalism of Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s inimitable style, while typically expressive, developed a tendency to crash into the realms of the expressly overwrought and the tangled, even by the standards of a polemicist. Qualms aside though, his films seldom dipped below the realm of inspiration, but that didn’t keep Lee from grasping for mainstream success. Pigeon-holed even though he didn’t deserve to be – his ‘90s output is a rainbow, a prism, of different, improbably variegated points of tonal and conceptual ingress to the subject of race – the ‘00s saw him on a vision quest for public acceptance, which unfortunately meant curtailing his polemical tendencies, excising race, or at least reducing it to the ghetto of the subliminal or implicit realm. The fruits of this shift were among his sharpest works – 25th Hour, Inside Man – but also among his more manicured and thus easily digestible, perhaps too judicious in their careful, almost ginger treatment of themes when Lee’s natural inclinations are for the dangerous.  Thirteen years after its release, one doesn’t have to look far to harness the consternation beating within Ang Lee’s tortured inferno of a motion picture. A poetic, lyrical, even hushed Shakespearean tragedy about generational sin and the disjuncture of personal selves, the film had the distinct whiff of a confidence trick when it was released in 2003 to superhero-hungry audiences. Rather than quenching adolescents’ Pavlovian bloodlust for improbable brutality, Lee’s film whispered sweet nothings of brash, brazen, smash-em-up violence in our ears and swindled us, harnessing that madman superhero energy and the cushy budget into a thoughtful, vital study on personal identity that mirrors, more or less, Lee’s own misfit status as a sensory-minded, sensitive art-cinema poet donning mainstream, blockbuster airs.

Thirteen years after its release, one doesn’t have to look far to harness the consternation beating within Ang Lee’s tortured inferno of a motion picture. A poetic, lyrical, even hushed Shakespearean tragedy about generational sin and the disjuncture of personal selves, the film had the distinct whiff of a confidence trick when it was released in 2003 to superhero-hungry audiences. Rather than quenching adolescents’ Pavlovian bloodlust for improbable brutality, Lee’s film whispered sweet nothings of brash, brazen, smash-em-up violence in our ears and swindled us, harnessing that madman superhero energy and the cushy budget into a thoughtful, vital study on personal identity that mirrors, more or less, Lee’s own misfit status as a sensory-minded, sensitive art-cinema poet donning mainstream, blockbuster airs.  Call it whatever you’d like, but this all-black modernization and loosening-up of The Wizard of Oz sure ain’t business as usual. Following the script but rereading the lines, altering the inflections, and considerably jazzing up the razzamatazz, the all-black The Wiz is ironically a loaf of white bread behind the screen (black stars became popular during this time, but black directors and writers, and thus control of movie sets and structure, and potentially control of white underlings, was still verboten by the Hollywood elite). Headed up by the hippest cat in town, Sidney Lumet, fresh off of simmering New York to a boil in Dog Day Afternoon and blowing his top in Network, this film is Lumet’s first old-fashioned NYC acid-trip.

Call it whatever you’d like, but this all-black modernization and loosening-up of The Wizard of Oz sure ain’t business as usual. Following the script but rereading the lines, altering the inflections, and considerably jazzing up the razzamatazz, the all-black The Wiz is ironically a loaf of white bread behind the screen (black stars became popular during this time, but black directors and writers, and thus control of movie sets and structure, and potentially control of white underlings, was still verboten by the Hollywood elite). Headed up by the hippest cat in town, Sidney Lumet, fresh off of simmering New York to a boil in Dog Day Afternoon and blowing his top in Network, this film is Lumet’s first old-fashioned NYC acid-trip.  Francis Ford Coppola’s great folly One from the Heart splintered the American New Wave/New Hollywood into shards of half-remembered former glory, casting the great American directors of the ‘70s across the land and possibly abetting the groundwork for the most corporate decade of all American cinema next to come. The famously impossible shoot of Apocalypse Now nearly killed him, of course, and for his next film, he wanted to gift himself a present, much as Michael Cimino did when his The Deer Hunter garnered award after award and he granted himself passage to direct his own pocket passion project Heaven’s Gate. Now, the New Hollywood barely survived Heaven’s Gate, the baroque masterpiece masquerading as a misfire, a grand accident of a film about the grand accident of America. But One from the Heart? The already rickety New Hollywood, a house on stilts with the whirlwind of Star Wars and other new-fangled pop cinema just waiting to topple it, couldn’t survive another go around.

Francis Ford Coppola’s great folly One from the Heart splintered the American New Wave/New Hollywood into shards of half-remembered former glory, casting the great American directors of the ‘70s across the land and possibly abetting the groundwork for the most corporate decade of all American cinema next to come. The famously impossible shoot of Apocalypse Now nearly killed him, of course, and for his next film, he wanted to gift himself a present, much as Michael Cimino did when his The Deer Hunter garnered award after award and he granted himself passage to direct his own pocket passion project Heaven’s Gate. Now, the New Hollywood barely survived Heaven’s Gate, the baroque masterpiece masquerading as a misfire, a grand accident of a film about the grand accident of America. But One from the Heart? The already rickety New Hollywood, a house on stilts with the whirlwind of Star Wars and other new-fangled pop cinema just waiting to topple it, couldn’t survive another go around.  If only Nicolas Cage could find a home. Werner Herzog was one once (in a much more harrowing caricature of New Orleans than Zandalee). Charlie Kaufman was another. Cage’s uncle Francis (yes Coppola) could have been one had Coppola still been granted passage to his inner delirium by the time nephew Cage was already acting. As a baroque, unhinged stylist, Cage is the ideal interpreter for a subset of directors who can channel him – or unleash him with a purpose – but too often, he’s left wandering the land, ambling around like a grotesque freakshow disfigured of rhyme or reason, and not in a good way. Despite what you might think, the problem isn’t new either; it’s an age old conundrum, one that Cage has less solved than exacerbated, but rare glimmers of beauty always secrete out of his frothing mouth when it’s in full-on walking abomination mode.

If only Nicolas Cage could find a home. Werner Herzog was one once (in a much more harrowing caricature of New Orleans than Zandalee). Charlie Kaufman was another. Cage’s uncle Francis (yes Coppola) could have been one had Coppola still been granted passage to his inner delirium by the time nephew Cage was already acting. As a baroque, unhinged stylist, Cage is the ideal interpreter for a subset of directors who can channel him – or unleash him with a purpose – but too often, he’s left wandering the land, ambling around like a grotesque freakshow disfigured of rhyme or reason, and not in a good way. Despite what you might think, the problem isn’t new either; it’s an age old conundrum, one that Cage has less solved than exacerbated, but rare glimmers of beauty always secrete out of his frothing mouth when it’s in full-on walking abomination mode.