Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice.

Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice.

This introductory image of the fire next time, both demonstrative and agnostic, willing to declare solutions with moral conviction and then pessimistically pockmark this conviction with shades of doubt, potently evokes the spirit of a filmmaker who has a certain feverish commitment to the belief that Hollywood style is a viable idiom for African-American stories – that the tools and tricks of old-school melodrama and cliche can be nervously renewed – and that these convictions must be interrogated. Like so many classical Hollywood films, Singleton’s vision is brashly direct in its viewpoints, but its confident forward stride belies a real shiver of hesitation. Not only a suspicion of its own decisions, mind you, but a mistrust of anyone’s ability to answer the fatalistic quandary – the choice between retaliatory violence and ostensible, possibly ephemeral peace – that genuinely emanates from the souls of these characters, a decision which we are all hopelessly unqualified to make.

Particularly telling is the way Furious Style’s sermon-esque pronouncements about institutional racism, with their flair for the didactic, suggest a personal anxiety about his son’s future which is nonetheless beholden to certain stuffy markers of respectability politics which the film, ultimately, can’t but query and reconsider as it goes along. It engages the supposedly faultless morality of mainstream society, with its presumably clear-sighted attitude toward rejecting violence, by considering the severity of ground-level conditions which perhaps preclude such ethical guarantees, all without dismissing the consequences of the actions perpetrated by the characters within.

Or without forgetting those characters. Where Ice Cube’s Doughboy becomes the ultimate moral avatar of the Faustian bargains made for success, or even survival, in the hood, there’s no sense that this is a screenwriter’s contrivance, or a hand-wringing moral imposition. Rather, it takes the form of a poetic evocation of the tragic inevitability of life on the streets, a sense of grim permanence that implies not the nihilistic denouncement of any possibility of change but the frightening cyclicality of a recurring nightmare. One that, perhaps, the characters could still hopefully wake up from. In the film’s artistic zenith, much more troubling than Ricky’s famous, melodramatic demise, his brother Doughboy suffers a final, vaporous disintegration, a ghostly reminder that some forms of escape go unvisualized, maybe cannot be visualized, in and by a film that nonetheless strives to materialize the potentially unimaginable dream of a fuller life.

Original Review:

With the release of Straight Outta Compton taking the world by storm, let us turn back the clock to a cinematic statement of urban life featuring the initial breakout star of the musical crew.

Occasionally, there are seismic shifts in the Hollywood landscape. The early ’90s influx of films made by and focused on African Americans doesn’t exactly fit the bill (it was cleansed from production schedules almost before it began, but vestiges retain, and a rebirth over the past few years, befitting the mid-2010s nostalgia for early ’90s culture, is still on the rise). For a while though, Spike Lee, John Singleton, and a few other African American filmmakers were unleashing some of the most vicious cinematic dogs upon society that America had seen in quite a while. The early ’90s were not happy times for Americans, and the recession brought forth increased public awareness of inner city poverty. With it, Hollywood wanted to do as it does and shed a little light on such problems in a way that ’80s cinema had uniformly overlooked. Continue reading →

Due to ease of access, I’ll be covering 1974 and 1975 before 1973.

Solaris is many things, but it is most of all the greatest answer film in all of cinematic history. By 1968, Andrei Tarkovsky had already earned the cinema’s eternal respect and humility by debuting as a major world director with the greatest film ever released about the nature of spirituality as it exists in relation to humanity, as it is felt in the senses. He clearly saw the light in Andrei Rublev, but it asked him not to falter or recede, but to continue to preach his gospel. Eying Stanley Kubrick’s eternally cryptic, disquieting, rigidly and pointedly mechanical work of genius, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky plainly grasped the film as a battle cry, as I certainly am not the first to notice. It was Western, for one, and scripturally infested in machines and production, and Tarkovsky was so fundamentally a bleeding-heart humanist that even the early Soviet focus on labor and metal had no use for him, let alone a Western focus on materialism. With 2001 shaking its head at humanity’s ambition and positing a certain greater humanity found in space we could never hope to understand or know, Tarkovsky no doubt refuted the ghostly specter and vast, echoing void of inhuman spaces in Kubrick’s film. Tarkovsky, essentially, felt a calling to bring out the guiding light for humanity once again.

Solaris is many things, but it is most of all the greatest answer film in all of cinematic history. By 1968, Andrei Tarkovsky had already earned the cinema’s eternal respect and humility by debuting as a major world director with the greatest film ever released about the nature of spirituality as it exists in relation to humanity, as it is felt in the senses. He clearly saw the light in Andrei Rublev, but it asked him not to falter or recede, but to continue to preach his gospel. Eying Stanley Kubrick’s eternally cryptic, disquieting, rigidly and pointedly mechanical work of genius, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Tarkovsky plainly grasped the film as a battle cry, as I certainly am not the first to notice. It was Western, for one, and scripturally infested in machines and production, and Tarkovsky was so fundamentally a bleeding-heart humanist that even the early Soviet focus on labor and metal had no use for him, let alone a Western focus on materialism. With 2001 shaking its head at humanity’s ambition and positing a certain greater humanity found in space we could never hope to understand or know, Tarkovsky no doubt refuted the ghostly specter and vast, echoing void of inhuman spaces in Kubrick’s film. Tarkovsky, essentially, felt a calling to bring out the guiding light for humanity once again.  Luchino Visconti sort of had it all, huh? A chameleon by trade, he spent a few decades hop-scotching from proto-Nouvelle Vague Italian Neo-Realism (Rocco and his Brothers) to ghostly melodramas (Senso) to gravid poetic epics with long takes like nitroglycerin by way of molasses (The Leopard) to out and out scorching the Earth with Molotov cocktails of Grand Guignol (The Damned). But his final masterwork was not a picture of succulent opera or intentional, declamatory fire or ice. It was simply a story of an elderly man, played by Dirk Bogard with melancholy sangfroid and still emptiness battling with impenetrable longing in his eyes, and the boy he comes to love while on vacation in Venice. It is an almost wordless work that consists almost exclusively of that man walking around and that boy walking around, and the two sometimes crossing paths with nary a word spoken between them. It is not necessarily Visconti’s best film, but it is his most misread, and possibly for the same reason, his most human.

Luchino Visconti sort of had it all, huh? A chameleon by trade, he spent a few decades hop-scotching from proto-Nouvelle Vague Italian Neo-Realism (Rocco and his Brothers) to ghostly melodramas (Senso) to gravid poetic epics with long takes like nitroglycerin by way of molasses (The Leopard) to out and out scorching the Earth with Molotov cocktails of Grand Guignol (The Damned). But his final masterwork was not a picture of succulent opera or intentional, declamatory fire or ice. It was simply a story of an elderly man, played by Dirk Bogard with melancholy sangfroid and still emptiness battling with impenetrable longing in his eyes, and the boy he comes to love while on vacation in Venice. It is an almost wordless work that consists almost exclusively of that man walking around and that boy walking around, and the two sometimes crossing paths with nary a word spoken between them. It is not necessarily Visconti’s best film, but it is his most misread, and possibly for the same reason, his most human.  And another Midnight Screening, because I had it prepared this week anyway, and because it celebrates the 25th anniversary of a personal favorite.

And another Midnight Screening, because I had it prepared this week anyway, and because it celebrates the 25th anniversary of a personal favorite.  It is with a heavy heart that I post this Midnight Screening on the occasion of horror maestro and professional boogeyman Wes Craven’s untimely demise. But what better way to honor his legacy than with a review of his best film?

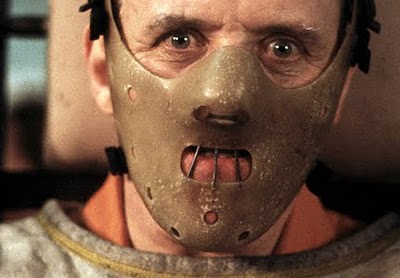

It is with a heavy heart that I post this Midnight Screening on the occasion of horror maestro and professional boogeyman Wes Craven’s untimely demise. But what better way to honor his legacy than with a review of his best film? What with all the hullabaloo around the televised Hannibal struggling to survive, let us turn our attention to the grand opus of the character and, with all apologies to Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the primary cause of the character’s continued social relevance today.

What with all the hullabaloo around the televised Hannibal struggling to survive, let us turn our attention to the grand opus of the character and, with all apologies to Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the primary cause of the character’s continued social relevance today. Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice.

Update mid-2019 upon John Singleton’s passing: It’s hard to single out one moment in Boyz ‘n’ The Hood without turning to the justly famous death of Ricky, perhaps the most famous moment in any early ’90s black-directed film. But my favorite will always be one of Singleton’s inaugural gestures. Or one of his opening salvos, more like it: a dramatically forthright early close-up of a Ronald Reagan poster, the ex-President decked out in cowboy hat and threads as the film tacitly stitches both the linkages between and the failures of his cinematic and presidential personas, both “sheriffs” promising to “clean up” the neighborhood via fascistically carceral rather than retributive, humanizing, and/or transformative methods. The film thus draws the connections between cinematic performance and presidential roleplaying, all while tracing the contours between Americana mythologies of Manichean justice, mid-century cinematic attempts to monumentalize said mythologies, and late-20th century neoliberal fetishes for unquestioned order. This film, of course, is set in a modern-day Wild West as well, and it suggests, within minutes, with Reagan’s visage assaulting the screen yet unable to attend to the humanity of any of these characters or the bullets which ravage his postered countenance, that this Los Angeles born-and-bred filmmaker was about to vandalize both the American government and the American cinematic tradition whilst acknowledging its potency, using the master’s tools to destroy the master’s house as it were, enacting a new, more humanistic, more inclusive, more egalitarian kind of wild west justice. Even among us independent, avant-garde, Europe-fried B-movie enthusiasts, there’s still a little mystique left in the idea of a runaround popular hit and an “event motion picture”, especially when that event doesn’t generally involve CG overload or a franchise player. Witnessing the robust box office success of Straight Outta Compton, and in particular witnessing Hollywood accept movies with black protagonists that explicitly address police brutality as valid events, is a refresher. Whether the film surrounding that event is good is not necessarily a given, for it is, after all, Hollywood making that motion picture, and likely subsuming the black audience and black characters into the generally white Hollywood machine. It is thus, perhaps, not a surprise that Straight Outta Compton, the film, never acquires the downright frightening, lightning-in-a-bottle social disarray of its subjects or the album that bears the film’s name. The film has some of that album’s braggadocio and bluster, and a little of its stylistic bravado, but precious little of the rip-roaring broadsides to conventional society and conventional artistic practices.

Even among us independent, avant-garde, Europe-fried B-movie enthusiasts, there’s still a little mystique left in the idea of a runaround popular hit and an “event motion picture”, especially when that event doesn’t generally involve CG overload or a franchise player. Witnessing the robust box office success of Straight Outta Compton, and in particular witnessing Hollywood accept movies with black protagonists that explicitly address police brutality as valid events, is a refresher. Whether the film surrounding that event is good is not necessarily a given, for it is, after all, Hollywood making that motion picture, and likely subsuming the black audience and black characters into the generally white Hollywood machine. It is thus, perhaps, not a surprise that Straight Outta Compton, the film, never acquires the downright frightening, lightning-in-a-bottle social disarray of its subjects or the album that bears the film’s name. The film has some of that album’s braggadocio and bluster, and a little of its stylistic bravado, but precious little of the rip-roaring broadsides to conventional society and conventional artistic practices.